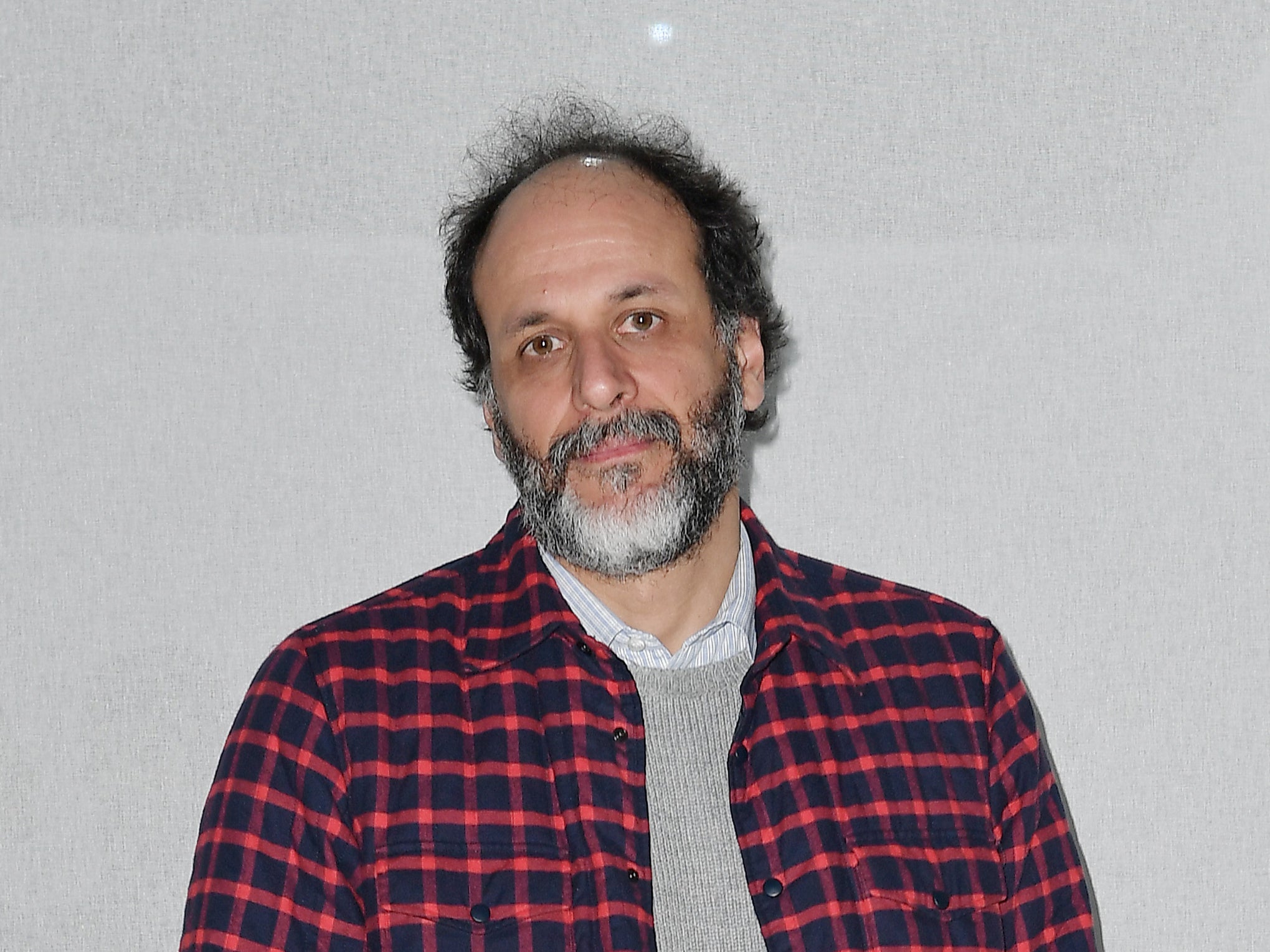

Luca Guadagnino: ‘I don’t have the right to decide whether an actor is straight or not’

The Italian director of ‘Call Me by Your Name’ tells Geoffrey Macnab why he rejects criticism of him casting straight actors such as Timothée Chalamet in queer roles, and why his film didn’t need full-frontal nudity, plus his new documentary about the great Italian shoe designer Salvatore Ferragamo

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Luca Guadagnino speaks like he makes movies. That’s to say, the director of A Bigger Splash and Call Me by Your Name riffs away in a provocative, poetic, free-flowing stream of ideas. English isn’t the Italian’s first language, but he can still express himself clearly enough in it. If Guadagnino doesn’t know a word, he will make one up.

We meet early on a Sunday morning in the Burano/Torcello rooms in the Excelsior Hotel on the Venice Lido. The interview begins with a Covid-related negotiation: “I’ll take mine off if you’ll take yours off.” We both agree not to wear our masks.

The Italian director, who has just made the eight-part coming-of-age series We Are Who We Are for HBO and Sky Atlantic, is speaking on the day of the Venice Festival premiere of his feature documentary, Salvatore: Shoemaker of Dreams, which tells the story of Salvatore Ferragamo (1898-1960), the luxury shoe designer.

Our talk ranges widely, but inevitably we revisit Guadagnino’s adored coming-of-age, romantic drama, Call Me by Your Name (2017), which won a Bafta and an Oscar for its adapted screenplay, and launched actor Timothée Chalamet towards superstardom. It tells the story of a love affair between Chalamet’s precocious teenager, Elio, and the young academic Oliver (Armie Hammer), who spends the summer helping Elio’s father, an archaeologist, with his research.

There is no reason, Guadagnino suggests, why he and his collaborators can’t continue creating “more stories” about the Call Me by Your Name protagonists. He lists those protagonists as if they are real-life acquaintances he hopes to catch up with soon. “At the end of the day, Elio, Oliver, Sam, Marzia, Mafalda – those are really interesting people and I am curious to know what will happen to them in life.”

The Italian isn’t suggesting a conventional sequel but, rather, that he will revisit his old friends, Oliver, Elio and co in the same way that François Truffaut kept on making films about Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud) over a period of 20 years, from The 400 Blows in 1959 to Love on the Run in 1979.

The otherwise genial and enthusiastic Guadagnino briefly becomes testy, though, when I remind him about venerable screenwriter James Ivory’s criticisms of him for not showing full frontal male nudity in Call Me by Your Name.

“Nobody who knows my work can say to me with a straight face that I’m shy about male or female or other gendered nudity,” he protests at the very idea he was being coy or prudish. “So, the critique or note that James gave was, in a way, devoid of pragmatism or a relationship with the movie itself. My question to him is does this movie need full frontal male nudity. I don’t think so. It doesn’t.

“Maybe the script which he wrote – which was a draft which then I reworked with my editor – was compelled to tell this story through the perspective of a very expositionary kind of nudity. But that would have been his idea of the movie which, unfortunately, we haven’t seen… so I don’t know.

“I think James was a little tone deaf about the situation.”

Predictably, Guadagnino does not much like my following question either. Is it appropriate, I wonder, to cast straight actors (like Chalamet and Hammer) as gay characters?

“I read too much Freud to be taking seriously these kind of critics,” he tuts. “Meaning that I honestly don’t believe I have the right to decide whether an actor is straight or not. Who am I to know what somebody is thinking of himself or herself within themselves. Yes, Armie is a straight man with a wife and children and the same can be said of Timothée. But do I ask them to swear on their sexuality, on their identities, on their desires, before I cast them? I don’t!” he exclaims.

“That sounds to be dull and a little preposterous. If I have to cast what people think is the real thing for a role, I wouldn’t be able to cast. I cannot cast a gay man to play Oliver. I have to cast Oliver to play Oliver because the identities of gay men are as multiple as the flowers in the realm of earth. So, there is not a gay identity. One person who is gay is completely different to another person who is gay.

“So, if I have to be accurate to this kind of dull remark, I could cast Oliver but Oliver doesn’t exist. He’s a creature of [writer] André Aciman. We go back to the last point I want to make which is that the beauty of acting is the possibility of the creation and embodiment of new selves through the art of acting.”

When he thinks of “a great portrait of a serial killer”, he adds, his first point of reference is Anthony Hopkins in Silence of the Lambs. “Does Mr Hopkins need to be a serial killer himself to play that role?”

Guadagnino is much happier talking about Shoemaker of Dreams, which has the feel of a passion project. In recent years, cinemas have been full of fashion movies and documentaries. Valentino, Coco Chanel, Alexander McQueen, Yves Saint-Laurent and others have all had their lives and works pored over on screen, stitch by painstaking stitch. For all I know, Guadagnino might share Ferragamo’s foot fetishism and admire all those exquisite designer shoes he made but, when you speak to the 49-year-old director, you realise his real obsession is actually with how Ferragamo became Ferragamo. How did a poor, uneducated kid from Bonito, “a village from which there is no escape” as the designer called it, transform himself into “a shoemaker of fashion, distinction and style”, whose shoes were worn by the biggest Hollywood stars and the grandest society folk?

Guadagnino was born in Sicily but spent his early childhood in Ethiopia, moving to Italy aged six and initially struggling to fit in. Now feted in Europe and Hollywood, he calls himself “an underdog”, just like Ferragamo.

In the documentary, Ferragamo (whose words are narrated by actor Michael Stuhlbarg, who played Mr Perlman in Call Me by Your Name) tries to explain his gift for shoemaking, which seems God-given. “The knowledge came back as if I had been reminded of a task I had forgotten, as if I was undergoing a refresher course of things I had learned in the past,” Ferragamo observed of his own creative process.

“The reality is that he was a genius; he had a great strong will and America embraced him,” Guadagnino says of how the humble shoemaker from near Naples travelled across the Atlantic to set up his own business. “Who knows what Salvatore in his upbringing, when he was very young, was absorbing. Then, these absorptions were processed within his identity, so he started to be able to make shoes, as if he knew it by a sort of… influence of the gods. It’s the subconscious, definitely. It’s also what an artisan is made of, the idea of forging a form from elements. This is something I am very fascinated by. At the end of the day, a movie is the collective contribution of a group of artisans who have to deal with ideas but also have to deal a lot with materiality – how to carve out from reality that something that is fictional [but] that looks real, sounds real.”

A master stylist, Guadagnino takes the same painstaking approach to making his films as Ferragamo once did to designing shoes. He shows the same pride and delight in his own work, too.

I ask about his plans to pick up Stanley Kubrick’s mantle and make a movie of Louis Begley’s autobiographical novel, Wartime Lies, the story of a Jewish boy and his aunt trying to survive in Nazi-occupied, wartime Poland by passing themselves off as Catholics. Kubrick had done a huge amount of research on the film, which he called Aryan Papers, and had cast Dutch actor, Johanna ter Steege, to play the aunt, but then, in the early 1990s, he suddenly abandoned the project.

Guadagnino may not be coy about nudity but he does appear reluctant to talk about future projects. He tells me he can’t discuss his planned remake of Scarface (from a screenplay by the Coen brothers). Nor does he provide many details about Aryan Papers beyond his passion both for Begley’s novel and for Kubrick and the fact that he has done plenty of his own research.

The interview comes to an end. He has Italian journalists to meet and a press conference to attend. Our talk of serial killers and full-frontal nudity is over. It’s time for us both to put back on our masks.

‘Salvatore: Shoemaker of Dreams’ premiered this week at the Venice Film festival

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments