Why Love Actually is not the heartwarming romcom you’re remembering

This festive romcom from Richard Curtin is outdated and treats women like pawns in a male fantasy, says Holly Williams

It’s December and that means Christmas films are very much on the agenda for the next few weeks, or are they?

If there’s one Christmas-themed film which does not deserved to be looked on charitably, it’s surely Love Actually.

Things have changed since 2003 – and having re-watched the movie, I can say in true Curtis sweary-Brit fashion, thank bloody Christ. For few films look as embarrassingly out-of-step with modern feminism as Love Actually.

It has become a romcom staple, and what the Americans call “holiday classic”, watched by millions each Christmas. Many fans are ecstatic at the thought of revisiting these characters. But – to use a phrase that definitely didn’t exist in 2003 – this fave is problematic.

Even on its release there were some grumblings about Curtis’ privileging of grand romantic gestures over character development. But even if it’s shown incredible sticking power, the film also dated rapidly. Increasingly, internet critiques recognise what a creepy version of romance it offers (most notably, Jezebel’s hilariously shouty take-down).

Because all the power and agency belongs to the male characters, while women – often their younger employees – are silent, appreciative, pretty things. The ones who have any cares or responsibilities beyond pleasing men seem to get punished, missing out on love and having to listen to Joni Mitchell.

It also seems astonishingly heteronormative: nine stories, all straight. Same-sex romance is gently mocked, but never made visible or celebrated (a lesbian scene was filmed, but cut). Obviously everyone hopes that the reunion will see ageing rock star Billy Mack and his devoted manager finally getting together. I’d bet on the lack of gay narratives being addressed in some way, at least.

What about the representation of women? We can but hope. Obviously, Love Actually is hardly the only film to present female characters as pure wish fulfilment. The industry has always been dominated by men. Most of the movies we watch are filmed from the point-of-view of the men, with women positioned as objects of desire to be acquired. But for such a beloved, really-not-that-old movie, Love Actually feels particularly egregious, stuffed with examples of passive women serving men’s needs and desires.

So, in an act of cold-hearted cynicism against the overly optimistic, saccharine romcom, here are all the ways the relationships in Love Actually make for really uncomfortable viewing.

Mark and Juliet

The sort of man who hires unwelcome “surprise” sex workers for his mate’s stag do is perhaps not a man with a vast well of emotional intelligence. But Mark – played by Andrew Lincoln – develops into a full-on creep. Secretly in love with his best friend’s fiancé (Keira Knightley), he films only her at the wedding. Often in extreme close-up, and certainly not saying anything: just a pretty face, over and over again. This wank tape is an almost comically blatant example of the male gaze in cinema: the camera literally frames his lust, the viewer presented Knightley through his adoring eyes. But it also seems to visually convey something about male control – he’s cropping her, containing her, imposing limits on the terrifying object of desire.

Because Mark is scared: scared of how much he likes Juliet. And yet he doesn’t even know her. Juliet says “but you never talk to me ... you don’t like me.” Mark has put her on a pedestal entirely because of the way she looks, with no regards to her personality or intellect. Maybe if he’d bothered to chat with her, he would have realised they had irreconcilably different viewpoints about the war in Iraq or the new Radiohead album or whatever else people talked about in 2003, and could have moved on.

Instead, we get the most famous scene of the film: Mark turns up to declare his love via the medium of giant hand-written signs, because it’s Christmas and we tell the truth at Christmas. Do we? Isn’t it the time of little white ‘I love it, you shouldn’t have’ lies? And this, after all, his best mate’s wife he’s calling “perfect”. Keep it under your Santa hat, Mark.

Sam and Joanna

Sam (Thomas Brodie-Sangster) is only a kid, but he’s totally, tragically in love with Joanna (Olivia Olson), the coolest girl in the school. She doesn’t even know he exists. But you’re never too young to start to learn how to “make” a girl like you. “I have a plan,” he declares. “Girls love musicians.” So he decides to learn to play the drums.

This plot is basically a mini-me Mark and Juliet. Why not try talking to her instead of just admiring her from afar? Maybe conversation would be better than pretending to like playing music to trick them into fancying you? To thine own self be true, little Sam.

Jamie and Aurelia

Poor handsome novelist Jamie (Colin Firth) is cheated on and has to go lick his wounds in France. His housekeeper is one Aurelia (Lucia Moniz), a Portuguese woman who speaks no English. They fall in love, despite being literally unable to communicate. In another big romantic gesture/arrogant gesture of male entitlement, he shows up at Christmas to ask her – his younger employee, with whom he’s never had a single conversation – to marry him. This comes across as at best shallow, at worst deranged. It’s wish fulfilment for the lazy romantic: getting the perfect girl without having to bother getting to know her.

The other really annoying thing about this plotline is the moment when they jump in a lake to save the pages of his book. Cue a lascivious slow-mo camera panning up and down Moniz’s body as she strips off to her underwear and executes a elegant dive, while Firth is allowed to flop in fully clothed, and splash about looking daft. Come on, Colin is famous for a wet-shirt scene – if we’re going to ogle, can it at least be equal opportunities ogling?

Sarah and Karl

We know it’s not going to end well for Laura Linney’s character Sarah: she wears frumpy skirts and big jumpers with terrible butterfly broaches. She also doesn’t prioritise romance and a man’s sexual pleasure above all else.

After the office party, dolled-up Sarah finally gets it on with her long-term crush, the hunky Karl (Rodrigo Santoro whose torso, granted, the film does linger on with female lustiness). But Sarah’s phone keeps going off, and she keeps answering. To be fair, it is her mentally ill brother who literally sounds like he’s about to kill himself. I like to think that most guys would get that. They’d be up for rearranging. Heck, maybe they’d even ask some questions, see how they could help…

Not Karl. Not in Love Actually. In rom-com land, apparently a man cannot share a woman with another man, even if it is her sick brother. And a woman cannot have her own life or responsibilities; she must at all times be available to service his needs. Back in woollens, Sarah.

Colin and all the American babes

When we first meet Colin (Kris Marshall), he gravely insults a wedding caterers’ cooking to her face. Instead of being embarrassed and apologetic, he decides that his problem is that British women are stuck up. He needs to go to America to pull.

Immediately, he meets three very hot girls, who adore his accent and end up taking back to theirs for an orgy. Of course, they are pure sex objects and this plotline is total male wish fulfilment – but at least the whole thing is played with its tongue in (some kind of) cheek, being comically, knowingly ridiculous. Or maybe by the end of the film I was just too tired to care.

Harry and Karen

Alan Rickman is the suave older boss Harry; his sexy young secretary Mia (Heike Makatsch), quite literally spreads her legs at him. She’s so seductively evil, she wears devil horns to a Christmas party. Does she think it's Hallowe'en? Who knows.

The woman is certainly doing the pursuing here – but the power and status is still all on his side. He’s the boss. She calls him “Sir”, for god’s sake (did anyone actually call their boss “Sir” in 2003?). And then there’s the business of her asking for a nice present from him, after the very obvious offer of sex. This is queasy, at best.

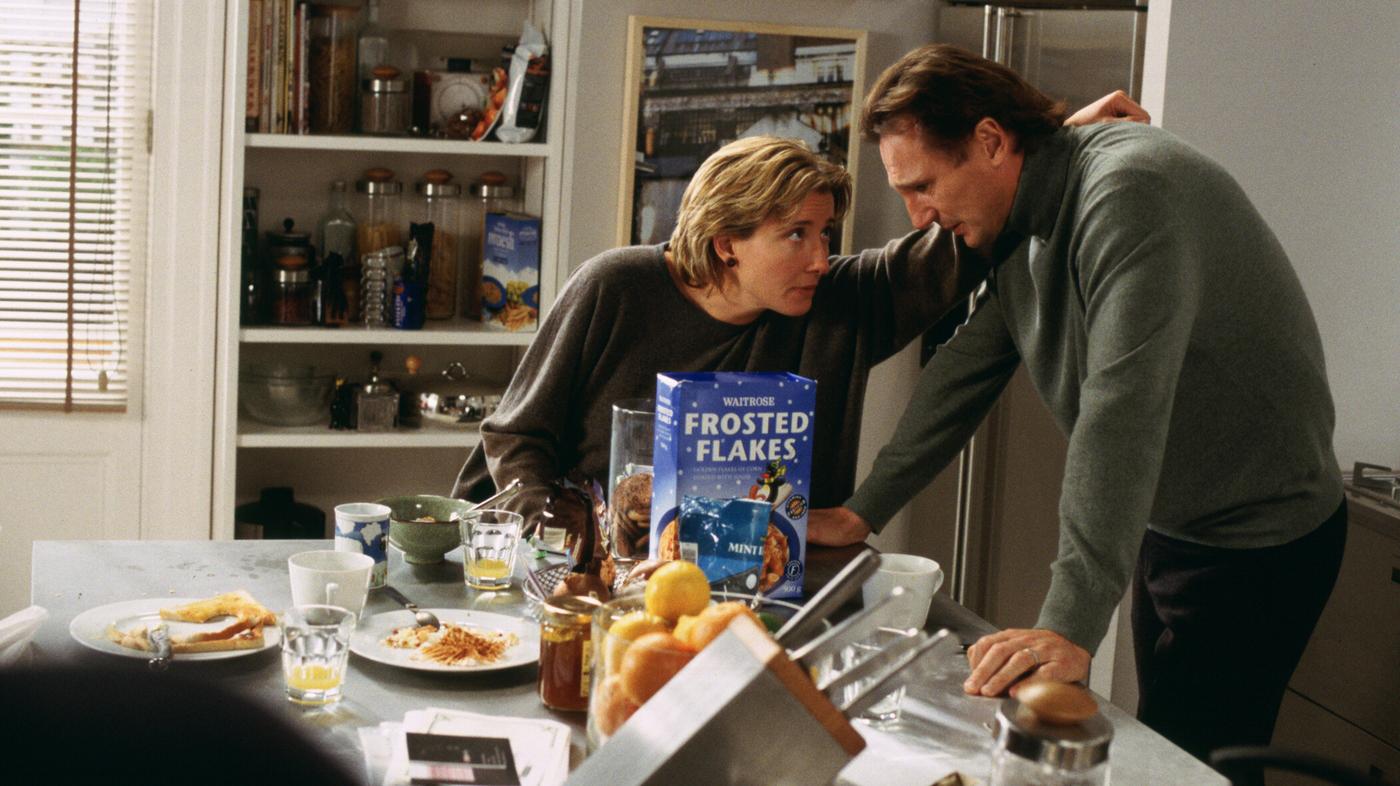

Then there’s poor Karen, Harry’s wife, played by Emma Thompson in the only truly human, multi-faceted performance in the film. She wears voluminous velvet, worries about being fat, and is a bit harried from running around after the kids (no sign of Rickman helping make their nativity play costumes, eh). Karen is also the only person we see looking sad in the film’s final montage of happy couples. Why? Because she isn’t a perky twentysomething bombshell? Because she challenges her husband about his behaviour and makes him feel bad?

The message certainly seems to be: only women who are sexy and make their men happy get their own happy endings. Screw you, Richard Curtis. That’s not OK, actually.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks