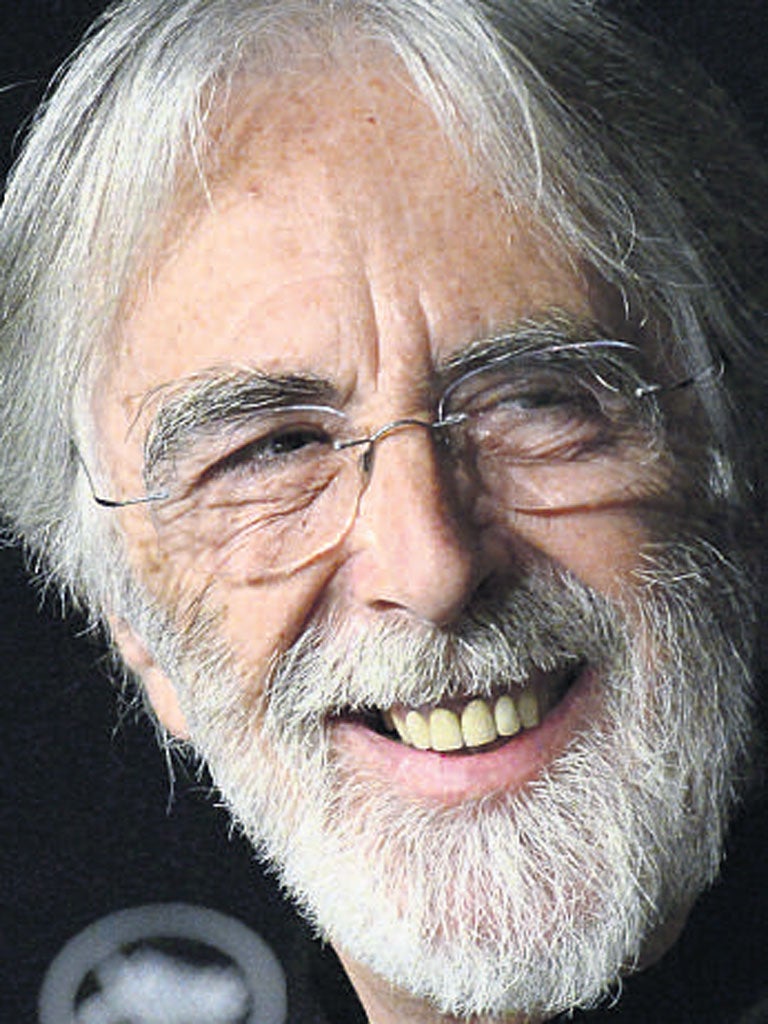

Love, actually, is Michael Haneke's big winner

The Austrian director has landed his second Palme d'Or in quick succession. Kaleem Aftab notes a change in mood

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.With his Palme d'Or victory for Love on Sunday coming just three years after he took the top prize for The White Ribbon, Michael Haneke has broken the record for the smallest amount of time between Cannes wins.

Love, about an octogenarian couple coping with their failing bodies and minds as illness has them staring at death, is a different type of film from the Austrian director. The easy-to-grasp tale marks a departure from the allegorical style that has bemused and delighted audiences in equal measure, a style that has made the 70-year-old director a favourite of academics, and numerous conferences have made stabs at parsing his work.

His films always seem to be about something else. Funny Games (1997), which sees a couple of young boys break into a house and torture a family, has been read as a comment on television violence, Hidden, about a couple terrorised by surveillance videos left on their doorstep, is seen as a comment on French colonial guilt over the Algerian war, and even his previous Palme d'Or winner, The White Ribbon, which is set in the run-up to the First World War, is actually about the Second World War and fascism.

Scratching of the head has often been the first reaction to watching one of his previous 11 feature films. Prior to his cinematic debut, The Seventh Continent, in 1989, he directed films for TV and had a short career as a critic. His very first career move was an attempt to follow his parents Fritz Haneke and Beatrix Degenschild into acting. He has also directed for the stage, taking on works from Strindberg, Goethe, Mozart, Bruckner and Kleist.

Isabelle Huppert, who starred in Haneke's The Piano Teacher (2001) and The Time of the Wolf (2003) and has a small but important role as a daughter living abroad in Love, says of the man she often cites as her favourite director, "he doesn't make the actors suffer, he makes the audience suffer."

This is usually done through brutal violence. Although it's often been a feature of Haneke's oeuvre that he doesn't show the violence; instead he lets the image linger on an open space, or just behind a door, and the audience imagines the brutality that's taking place just beyond the camera's stare. He seems to believe that nothing is as depraved as what goes on in our minds, and it's a guiding feature of many of his protagonists, most notably Daniel Auteuil's Georges Laurent in Hidden and Huppert in The Piano Teacher. In Love, once Anne (Emmanuelle Riva) has a stroke and suffers memory loss, her relationship with husband Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant) becomes a battle of the wills. Both believe that they know best: Anne wants to die, while Georges wants her to live, as much for his own wellbeing as hers.

In Cannes, Haneke said of a scene that takes place after Anne tries to commit suicide, and after George wheels her into the living room: "There is so much pain and suffering, I felt deeply moved and touched." Other themes seen in Love that commonly appear in his films are the failure of the family unit and women as victims of physical abuse.

Jean-Louis Trintignant, who came out of screen retirement after a 14-year absence from cinema, said: "I think that Haneke is one of the greatest directors in the world... But I've never met such a demanding director, he knows exactly what he wants his film to look like."

Haneke demands as much precision from his actors on-set as he exerts constructing his images on screen. He is also a professor of directing at the Vienna Film Academy, and then there is his look – I've only ever seen him wear black that always pops out against his white beard. For all the complexities of his storylines and characters, his basic message is that the human condition is framed by violence and selfishness. And yet the unveiling of Love at Cannes seemed to confirm another trend that has taken hold of his work since the failure of Hidden to win the Palme d'Or. That is that Haneke has started to make films using the techniques of Hollywood.

The big question is why in 2007 he decided to remake Funny Games with Hollywood stars. The film was a shot-by-shot transposition of his 1997 Austrian original, this time with Tim Roth playing dad and Naomi Watts the mother. It turned out to be a commercial failure, but what it also hinted at was a director seeking more acclaim for his own work.

Making films about the First or Second World War has also been a sure-fire route to awards success in America. When Haneke finally won the Palme d'Or for The White Ribbon, set in a village in the months before the First World War, it was as if a weight were lifted off his shoulders; he became a far more carefree and light-hearted figure, easier to interview.

Love is his most straightforward picture and a far more obvious film for an American remake than Funny Games. In becoming a bit more Hollywood, Haneke is finally getting the awards that his remarkable oeuvre deserves.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments