‘Harvey Weinstein would threaten to get Tarantino to direct’: An oral history of The Lord of the Rings at 20

To celebrate the 20th anniversary of ‘The Fellowship of the Ring’, Sam Moore speaks to Ian McKellen, Elijah Wood, Orlando Bloom and many more about on-set horse rivalries, the perils of making an ‘unfilmable’ adaptation, and how close Harvey Weinstein came to pulling Peter Jackson off the project

The Lord of the Rings hadn’t failed to make it to the big screen through a lack of trying. Everyone from the Beatles to John Boorman had attempted to put the quest to destroy the one ring on celluloid. Because of the merciless depth, intricate plot and vastly imaginative landscape of JRR Tolkein’s source material, though, it had long been considered unfilmable.

Ultimately, Peter Jackson – a highly regarded but largely untested cult filmmaker from New Zealand, then best known for his Oscar-nominated 1994 film Heavenly Creatures – realised the ambition and the scope of Tolkien’s work and made fantasy cool again.

Rounding up a cast of character actors (Viggo Mortensen, John Rhys-Davies, Sean Bean), newcomers (Orlando Bloom, Billy Boyd), the odd former child star (Elijah Wood, Sean Astin) and a British legend or two (Ian McKellen, Christopher Lee, Ian Holm) – plus Hollywood stars such as Liv Tyler and Cate Blanchett – a nearly two-year production schedule commenced in New Zealand, far away from the prying eyes of Hollywood.

But it nearly never was. In a story that features Harvey Weinstein, Quentin Tarantino and Aragorn being replaced a week before filming, the road to Lord of the Rings was almost as treacherous as the road to Mordor itself.

Twenty years after its release on 19 December 2001, the first chapter in the original trilogy, The Fellowship of the Ring, is as acclaimed now as it was then. Recently named the greatest film of all time by readers of Empire Magazine, The Fellowship of the Ring is also the rare blockbuster to be recognised at the Oscars, picking up 13 nominations in early 2002, and becoming a landmark in modern cinema. To commemorate the anniversary, Ian McKellen, Elijah Wood, Orlando Bloom and other key figures from the film recall the making of a cinematic classic.

‘Bob Weinstein suggested at one point that we kill three of the Hobbits’

Peter Jackson’s development of the films initially began at Miramax, the studio run by Bob and Harvey Weinstein. While the brothers were initially supportive of Jackson’s vision, things turned sour as Miramax’s corporate owners Disney controlled the studio’s pursestrings and refused to green light the budget needed for the films. As a result, Harvey gave Jackson and his team a seemingly impossible task to save their movie.

Ken Kamins (Peter Jackson’s manager): I remember Peter vividly telling me that the reason Lord of the Rings could get made was because technology had finally caught up with Tolkien’s imagination. After Heavenly Creatures was acquired by Miramax, Peter and [his wife and creative partner] Fran Walsh signed a first-look arrangement with the Weinsteins. It meant that any idea they had, it had to be presented to Miramax first.

Mark Ordesky (Producer at New Line Cinema): I’d known Peter from the late Eighties and I just wanted to work with him. When he first came to LA he’d sleep on my couch and we’d play Risk together. He actually wrote a script for a Nightmare on Elm Street sequel that we never used. As a transfixed Lord of the Rings fan, I had a terrible split reaction to it being at Miramax because as a young junior executive I’d tried to buy the rights. On the one hand, I was thrilled that it was going to happen with a filmmaker I loved. On the other, I was crushed that I was not able to participate.

Kamins: Harvey was excited. We found that very encouraging and thought we’d have room to tell the stories, only we weren’t paying attention to the political dynamic between Miramax and Disney. Disney had set a budget cap on Miramax and Lord of the Rings was well in excess of what they could greenlight on their own. When Disney realised the budget and that we were going to shoot the films back-to-back, and the director was not exactly an A-list name, they made it very clear they were not on board. So then begun the very tortured process of Harvey not wanting to admit to the Disney pushback and then at the same time saying to Peter, “This is what you have to do.”

Bob Weinstein suggested at one point that we kill three of the Hobbits. Disney didn’t want [the adaptation] and the relationship between Peter and Miramax soured. Harvey would go from acting empathetically to turning on a dime into Mr Hyde and would threaten Peter. He’d threaten to get Quentin Tarantino to direct if Peter couldn’t do it in one film that was two-and-a-half-hours – which was the exact opposite of what he initially told us he wanted. Eventually, I go to Harvey and say, “You have to give us a window to shop it.” A traditional window [to try and sell a property to a different studio] is between six and 12 months – Harvey gave us three weeks. He also wanted a $12m (£9m) advance to cover what Miramax had spent and five per cent of the total gross, and to be named as an executive producer. We had three weeks to sell Lord of the Rings to another studio or the rights were Harvey’s and he’d kick Peter off the project.

Ordesky: They were pursuing all the major studios and all the indie financiers, including New Line. I had spent probably 10 years rabbiting to [New Line founder] Bob Shea about Peter, and he was familiar with him through that Nightmare on Elm Street script. So Peter comes in with his presentation, which was a 30-minute video. It answered all the questions a studio would ask: how he was going to use real actors and make them appear three feet tall; how Gollum would manifest; why Peter was the right person to make the films.

Kamins: Bob Shea was a riverboat gambler. He rolled the dice and he took a shot.

Ordesky: It was actually Bob’s idea to do three films instead of two. The original pitch was to do two films and Bob goes “there’s three books, why are you only making two films?”

Kamins: He said, “Tolkien did your job for you. He wrote three books so you have three movies,” and I’m kicking Peter under the table not believing what I’m hearing. They said yes on Monday and were out of pocket $12m by Wednesday. Harvey was absolutely stunned. He set us up to fail and expected us to fail. But he got his five per cent.

‘Apparently Sean Connery read the material and just didn’t get it’

Despite Lord of the Rings being one of the most popular books of all time, A-list stars weren’t exactly queuing up for a part in the adaptation. Sean Connery said no to Gandalf, as did Daniel Day-Lewis. Instead, Britain’s finest thespian was shot to worldwide fame at the age of 60 and a journeyman actor named Viggo Mortensen became an action hero.

Ian McKellen (Gandalf): It never occurred to me that this would be the job of a lifetime. In fact it all went away after I agreed to do X-Men and the [filming] dates coincided with Lord of the Rings. When I told Peter Jackson I couldn’t do it, I felt quite sanguine. I was then in a restaurant and Bob Shea puts his hands on my shoulders and says, “I’m so glad you’re in our movie,” to which I say, “I can’t do it anymore,” and explain why. In that way all producers do, he says, “Leave it with me.” [X-Men director] Bryan Singer agreed to have me free of all obligations if Lord of the Rings could delay a couple of months. They only wanted me because the established stars said no.

Ordesky: Ian’s being self-deprecating. We desperately wanted him.

McKellen: They wanted Tony Hopkins and Sean Connery.

Ordesky: We did make an offer to Connery but he said no. We never got an answer until years later, but apparently he read the material and just didn’t get it.

Andy Serkis (Gollum): My agent called me and said they were making Lord of the Rings and would I be interested in doing a voice for a digital character. My first response was that there must be a dozen decent, conventional roles for me – I wasn’t a voice actor and never thought of myself as a voice actor. I started building Gollum psychologically, emotionally and physically, going through the book and taking Tolkien’s descriptions. When I was looking for inspiration, my cat came into my kitchen and started coughing up a furball. I watched his whole spine ripple and this sound coming out of him that was like a trapped voice, so I incorporated that into the audition.

Elijah Wood (Frodo): As you can imagine, every single living, breathing actor wanted to audition for it. I remember reading that Peter was making them and being excited because I loved Heavenly Creatures – he was such a perfect fit for this universe. I didn’t want to do a traditional audition because I find the process very fraught and it makes me nervous. I wanted to make the biggest impression I could, so I dressed up like a Hobbit and got a voice coach to work on the dialect. Then I went out to Griffith Park [in Los Angeles] and shot a tape from multiple different angles and sent that VHS to the casting director. Fast forward several months and Peter Jackson phones and asks if I want to be Frodo.

Dominic Monaghan (Merry): I read in a newspaper that they were trying to make the books and that Sean Connery was attached as Gandalf. I thought, “I must ask my agents about that.” As it happened, the casting director John Hubbard came to see a play I was doing in London and he tells me he wants me to audition for Lord of the Rings. I went in for a generic read, so most of the young male actors all read the same scene, which was Frodo looking at the ring.

Orlando Bloom (Legolas): I initially auditioned for Faramir, who would be played by David Wenham. They then call me and want me on tape for Legolas. Then it was another meeting with Peter and Fran. I remember my agent calling me to say I’d got the part and I was jumping up and down in my apartment. It was mind-boggling. I did not expect to go into a film right out of drama school.

John Rhys-Davies (Gimli): I originally auditioned for Denethor, who went on to be played by John Noble. I was a bit taken aback when they said they wanted me for Gimli, but in retrospect it was a brilliant bit of casting. I didn’t even think Lord of the Rings was going to work. I thought funding would fall out, but I’d get a month’s holiday in New Zealand.

‘If a director doesn’t cast right, he’s just burdening himself’

Irish actor Stuart Townsend was originally cast as Aragorn before being dropped in the days leading up to filming. He’d spent the entirety of pre-production in New Zealand, training and rehearsing with the rest of the cast before being replaced with Viggo Mortensen.

Rhys-Davies: Stuart is terrific but Peter realised pretty early on that he wasn’t going where he wanted him to. It was the right decision. If a director doesn’t cast right he’s just burdening himself.

Ordesky: It was scary when we learnt that Peter wanted Stuart out. I was in London and I got a call late at night telling me the news and I got down to making lists of actors: Russell Crowe, Jason Patric, Viggo Mortensen. Peter and Fran were already ahead of the curve as they were thinking about Viggo as well.

Kamins: I know it was a difficult decision for Peter and Fran but it wasn’t as if Stuart was making $10m. He wasn’t that guy. And it was early enough in the process for the studio to allow Peter to pivot. We lucked out with Viggo.

Rhys-Davies: Viggo was aware that there might be some concern among the actors who worked with Stuart. It’s always unsettling when somebody is asked to leave.

Monaghan: Viggo very quickly ingrained himself with the rest of the cast. You can’t imagine anyone playing Aragorn but him.

‘We went around New Zealand looking for the right type of hedge’

Creating Middle Earth was no small task. Seven units all filmed simultaneously and thousands of artists, craftsmen and visual effects people came together to create everything from the grass in The Shire to Gimli’s beard.

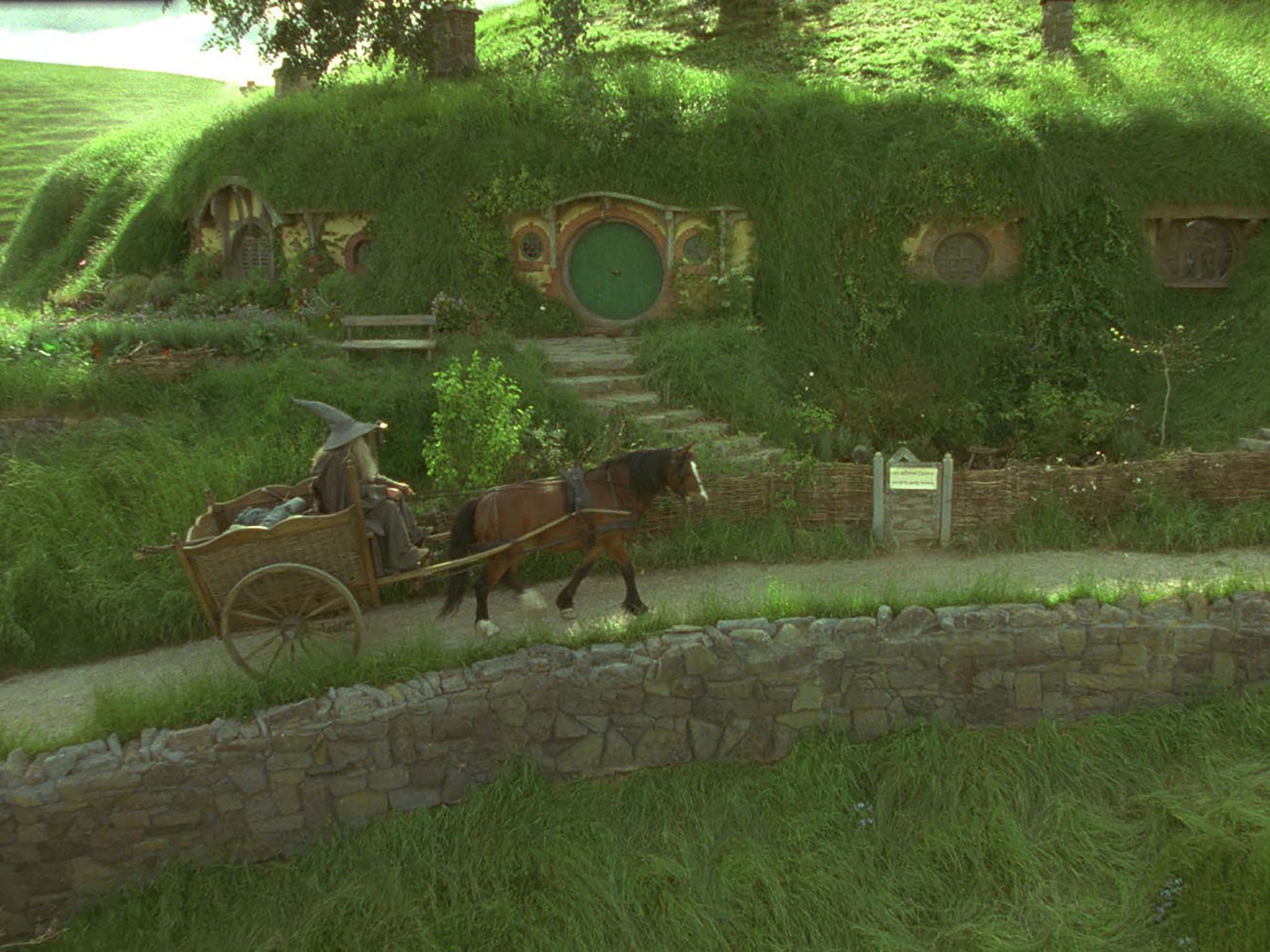

Grant Major (Production designer): It took an entire year to create The Shire. We found an area of rural New Zealand that resembled Tolkien’s descriptions and we had to persuade the farmer to let us use the land. Then we built everything. We’d lay out roads, build the houses, all the stone walls, it was really like building a town. We went around New Zealand looking for the right type of hedge and then we’d transplant it to the set. We’d grow and replant flowers, make sure the grass was the right length. It all took a year.

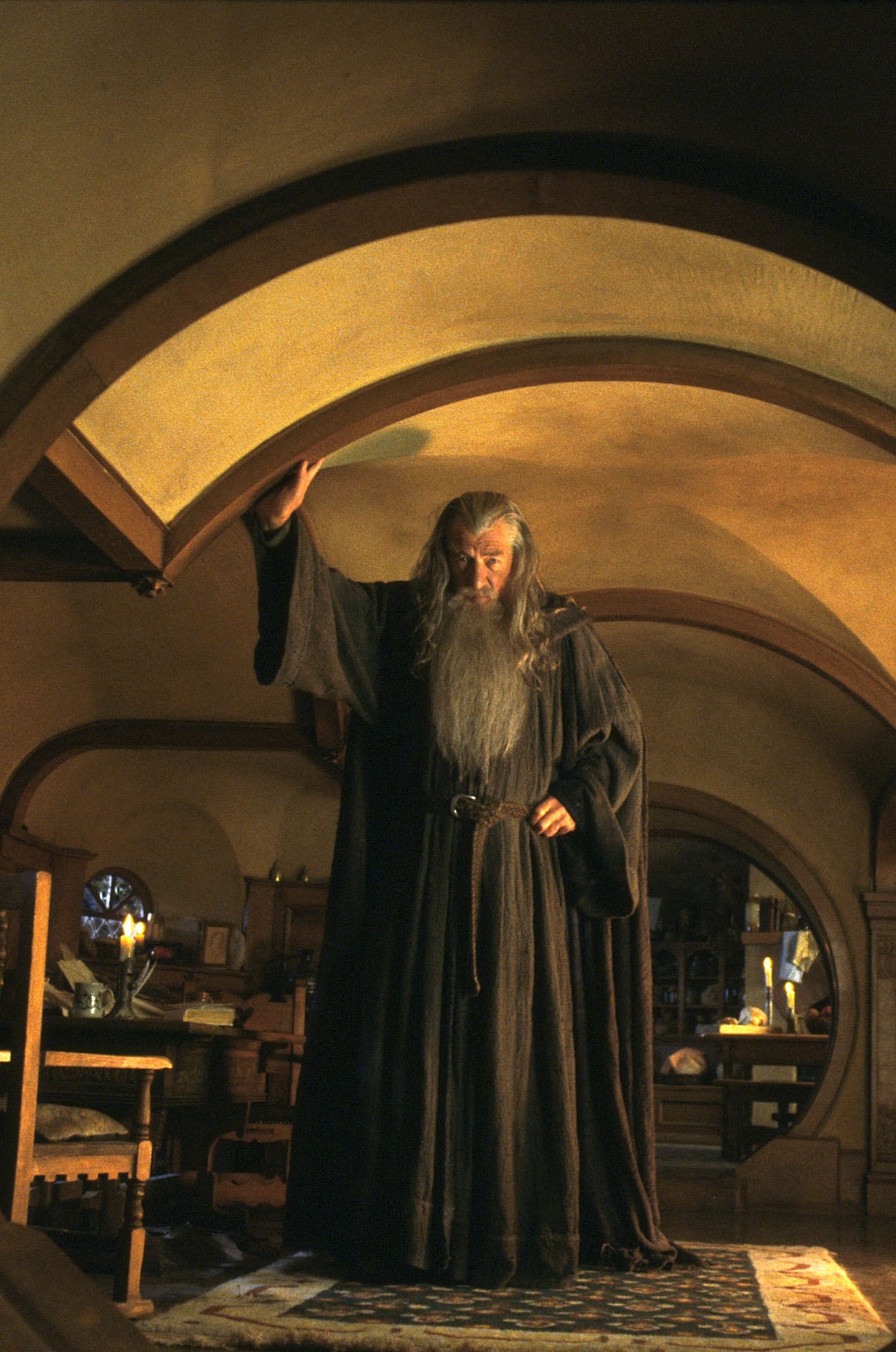

Dan Hennah (Art director): Peter always stressed that it was going to be big and he wanted it to be real. He didn’t just want to use furniture you got from the supermarket. Every single piece was our work. The fabrics were homespun, we established our own pottery, we made the glass, the cutlery in Bilbo’s house was all made. There was nothing in the films that wasn’t specifically made. For Bilbo’s house we thought about what he was like – he was an adventurer, a writer, he was an old guy who lived alone but he had seen things no one else had. And there were two versions of his house, one for Ian McKellen and then another for the doubles.

Hennah: We really treated the books like a Bible. In terms of the descriptions, what we wanted to achieve – we just looked at the books.

Major: Everything had to be designed at two different scales – one for the Hobbits and another for Gandalf. We had to work out how far apart the actors needed to stand. The Hobbits were originally three foot six but Peter changed his mind to four foot because it was what we could get in the film and that was how tall the doubles were. It was all done mathematically. We had to use scaleable material like wood and paper too.

McKellen: I never really got over having to work with scale. I’d be standing on a box or Elijah would be on his knees. If we had a two shot I couldn’t look into his eyes and vice versa. I had to look at his midriff and he’d be looking at the tip of my pointy hat. The scale doubles were a large part of it too. They found a very large policeman called Tall Paul to double me.

Monaghan: Tall Paul was often our Gandalf. He was like seven foot and we’d be on our knees. Ian would still be on set, unless it was just a walking shot. It was never just a day with the double, Ian was always there and we were always with Ian.

McKellen: Spending time on Gandalf’s appearance was very helpful to me. I just sat in front of the mirror trying on all these different wigs and beards and moustaches and eyebrows. I’d stick them on and people would come in and out telling me what they thought. I began with a beard which went down to my knees, which is how it’s described in the book. But that wouldn’t work for a film that is supposed to be real, it’d look ridiculous.

Monaghan: When we had to work with special effects, Peter was great at painting those mental pictures for us. Everything was so descriptive, but the reactions from all of us were pretty organic because we’d never experienced anything like this before.

Rhys-Davies: [My] prosthetic was brilliant, but it needed a high quality adhesive and it bonded to the outer layer of my skin. It’s not designed to be taken on and off again and each time you do it, it takes away a layer of cells. In the end, the irritation factor meant you were itching to the point your entire face becomes swollen. It was tough on me.

Serkis: When I was cast, they weren’t sure whether it was going to be just animation or something more, but Peter wanted an actor on set. His thinking was, “Why should the other actors have to imagine something when Gollum is actually driving a lot of these scenes?” When I got to set, Peter said, “We’re going to film you and we’re going to use your physicality.” Firstly I was filmed with the other actors, then I’d come back later on to do the motion capture stage and recreate those movements. It wasn’t a difficult process. I’ll never forget seeing myself puppeteer Gollum for the first time – lifting my right hand with Gollum staring back at me and lifting his was extraordinary.

‘If I had a tattoo for every movie I’ve done, I’d look like the illustrated man’

Spending nearly two years together made the cast as close as family, with many remaining friends to this day. The camaraderie on set became symbolised by the tattoo each of the nine members of the fellowship got to mark the making of the movie.

Monaghan: Our first day filming was the Hobbits rolling down the hill and falling on top of each other. I think Peter purposely started with just the Hobbits. We did a lot of work together before our scenes with Ian and Viggo.

Wood: It was really exciting getting to work together on that first day. Us Hobbits had a real bond with each other and it was lovely that all our stuff at first was together.

Monaghan: My horse absolutely hated Billy Boyd’s horse. I have no idea why they put them together. We were always together and all the horses would do was bite each other. I also wore a fat suit on the first movie – by the second I’d put on a couple of stone in the gym and I didn’t need the fat suit anymore but they did tell me to stop going to the gym as they’d have to keep making bigger clothes for me.

Rhys-Davies: I so enjoyed working with that cast, even if I was a bit of a loner at times because of the disfigurement from the prosthetic.

Bloom: John was a really good sport. It was really challenging for him with the makeup but he always nailed every scene.

Rhys-Davies: All the girls ask me what it was like hanging out with Orlando, to which I have to gently point out that he was 20 and I was 55. If I’d been hanging out with him a lot it would have been a cause for concern. He was perfect for that role – just raw talent.

McKellen: I had a pocket sewn into my costume that I could fit a copy of the book in. The atmosphere on the set was so friendly. It felt like we were in a big home movie. Film sets were never comfortable places for me but Jackson created a lovely atmosphere. You wanted to be there and help everybody out.

Serkis: I had quite a solo experience on the set and that suited me because of the character. The cast I got to know was really Elijah and Sean Astin [who played Sam] and while it took some time to figure out exactly what was going on, they were incredible. When you’re doing a scene and just looking into an actor’s eyes, it doesn’t matter what you’re wearing, you’re just acting. The fellowship had their camaraderie, going off to get tattoos, so the people I spent the most amount of time with were the visual effects team.

Rhys-Davies: If I had a tattoo for every movie I’ve done, I’d look like the illustrated man. The drunken elves and Hobbits came back from a night of debauchery in Christchurch declaring that they had this great idea to get a tattoo celebrating the making of the film and the fellowship of the nine. As I was a member of the fellowship, they said I had to have one, too. I objected, they insisted, I declined, they persisted. Finally I relented and did the wisest thing an actor can do when faced with a challenge that can be life-threatening – I sent my stunt double.

Bloom: I don’t remember it like that. In New Zealand, tattoos are a big thing with the Maori and I remember thinking I wanted to get a tattoo. I thought it would be a cool gift. So I told Viggo – he finds this great artist and we scheduled ourselves in. I tried to convince John but he thought we were poisoning ourselves. In the end Bret Beattie, his stunt double, [got it instead]. We have photographs of the moment we all got it done and we were going to keep it secret but it was such a great story that it just took off. I think Ian was the first one to show his on a TV show.

‘He liked nothing better than gossiping about long dead actors’

The late Christopher Lee, star of over 200 films and an icon of horror cinema, was cast as the villainous Saruman and by all accounts was a delightful man. He would have been 100 next year.

McKellen: When I first got to New Zealand, Peter invited me to a restaurant and sat me next to a certain actor who was playing Saruman. He announced when meeting me that he had read Lord of the Rings and always thought he should have played Gandalf.

Monaghan: He was larger than life. Literally. He was like, six foot six with this big booming voice. He would regale us with stories about Marlon Brando and Marilyn Monroe and Errol Flynn and I’d just gush listening to him. He was on the front line in the Second World War doing some crazy stuff and I watched him once take a pen and throw it at a tree and it stuck into the tree like a knife. He was an impressive gentleman.

McKellen: He did not take his career lightly. He’d expect you to know who he is but nothing more than that. He was getting on at that point, but his wife would be there to guide his offscreen life. He liked nothing better than gossiping about long dead actors and telling stories about Larry Olivier. I think he would have liked to have been considered in the same category as someone like Ralph Richardson. Receiving the knighthood gave him great pleasure.

Ordesky: Christopher Lee was the best dinner guest you’ll ever have. His most boring story is somebody else’s best story.

‘I said “The Fellowship of the Ring” was going to be bigger than the new “Star Wars”’

Upon release, The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring became the fifth highest-grossing film of all time and left an immeasurable impact on the creative and tourist industries of New Zealand. Twenty years later and fans from all over the world still travel to see filming locations. With an Amazon TV adaptation of Middle Earth on the way, Tolkien’s lore holds as strong as it ever did.

Rhys-Davies: I remember the press being suitably sceptical about Peter Jackson and me saying to them that they needed to revise their expectations upwards. I said The Fellowship of the Ring was going to be bigger than the new Star Wars and Peter put his head in his hands.

Major: For New Zealand, there was really before Lord of the Rings and after Lord of the Rings. A huge amount of the population was involved in the film in some way. The government came on board and gave us access to spaces we wouldn’t otherwise be allowed in, such as the ecologically sensitive areas. As a result of the films, tourism just took off in New Zealand and so many people still come here because of them.

McKellen: I remember a friend saying to me that my life was going to change and I didn’t believe them. I’m known as Gandalf to people who have never seen me in anything else. I don’t resent that at all – a lot more people have seen me play him than King Lear or Richard III.

Rhys-Davies: I have a 15-year-old daughter as a consequence of my revisiting of New Zealand [Rhys-Davies met his current partner, TV presenter Lisa Manning, while promoting the films]. She’s never seen it, she’s never even seen Raiders of the Lost Ark [in which he played Indiana Jones’ sidekick, Sallah]. But I’ve taken her to fan conventions in the past and she was very proud to stand by me and reassert that this is her daddy.

Bloom: I have a real blind spot about a lot of that period [after the release of Lord of the Rings and Pirates of the Caribbean] because my life was moving so fast. It was wild and I wasn’t very good at hiding myself. I didn’t have a lot of people I could talk to about that level of fame. It was such an odd one. But I actually revisited the films for the first time in lockdown with my son because he hadn’t seen them before. That experience on Lord of the Rings informed everything else I’ve done with my life. My son was a big fan of the film and he’s a pretty nonchalant kid. He lives a unique existence – not many kids can say their dad is an elf and a pirate. I’m just grateful for the whole thing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks