Legend: An in-depth look into the violent history of Ronnie and Reggie, the Kray twins

Ronnie, Reggie and the legend of ‘old-school’ villainy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The flowers are all dead. I’m standing by the grave of Ronnie and Reggie Kray in the rain, looking down at stalks and plastic wrap.

There have been no fresh tributes for a while and the weeds are taking over. The Krays were once called the most evil men in Britain, the most feared twins in history, the most infamous gangsters the East End has ever produced – but in this quiet corner of Chingford Mount Cemetery they seem forgotten.

Soon that will change. A superb new movie called Legend, starring Tom Hardy as both the Krays, will bring new pilgrims and dark tourists to this place. But, for now, it is quiet as the rain hisses in the trees.

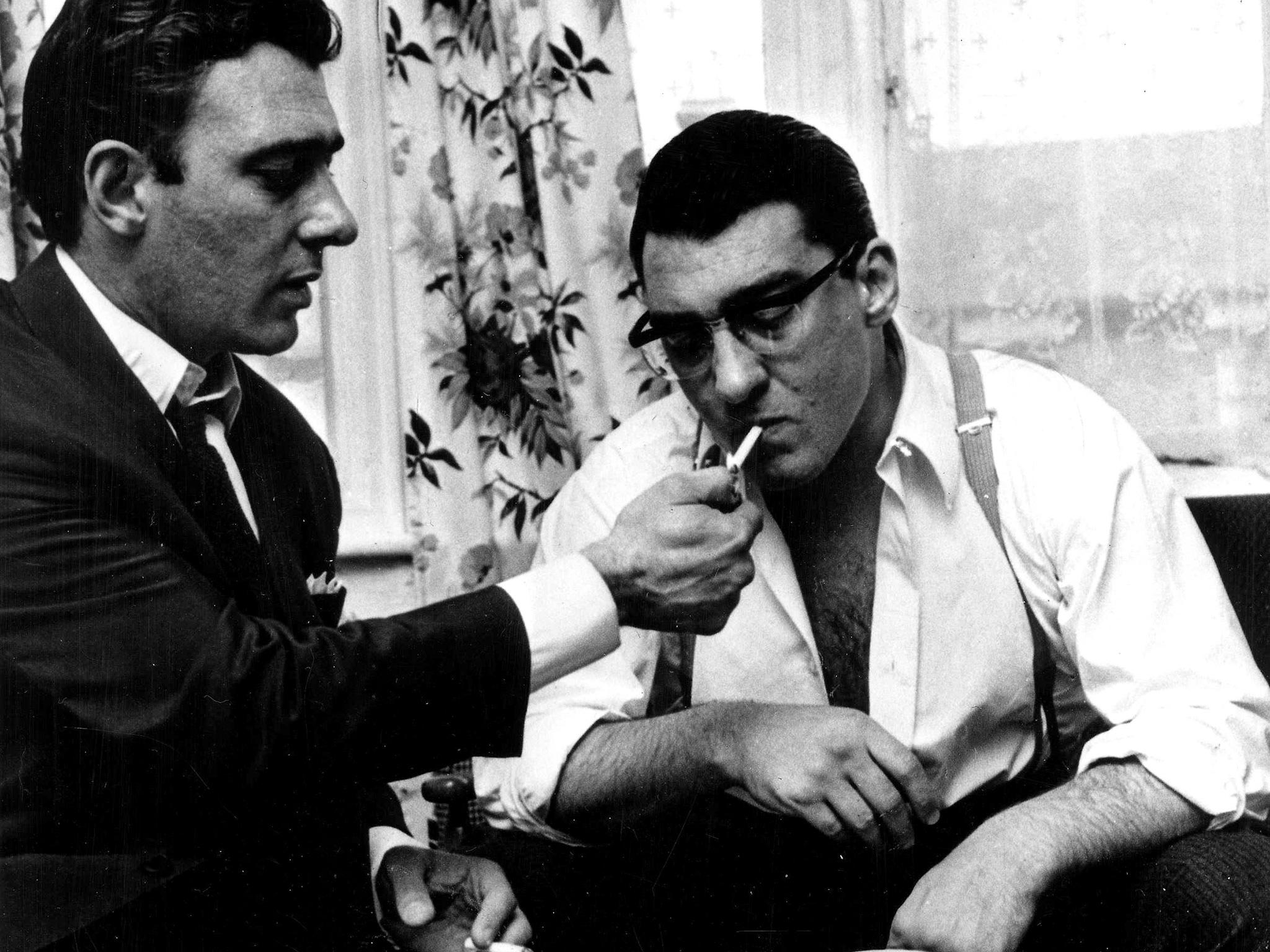

The faces of Ronald and Reginald Kray are reproduced, on glistening black marble, as they were in a famous photograph by David Bailey: in the dark suits, white shirts and slim ties that gave these bad men glamour. “Grant them eternal peace, O Lord,” says the inscription, but they gave no peace to those they intimidated, extorted money from, beat up, stabbed or shot during the Sixties.

To their mother, Violet, buried close by, they were “my lovely boys”. I have been to this place before, but it is the first time I have paid attention to the more ornate headstone next to theirs. Built at the height of their fame, it marks the passing of Reggie’s wife. An angel looks down in sorrow at a little white model of a Scottie dog. “Frances Kray, passed away 7th June 1967, aged 23 years”.

The Krays went to prison for murdering fellow gangsters George Cornell and Jack McVitie. Frances, or Frankie as she was known, was described by people who knew her as a beautiful innocent, who died as a result of contact with them. On the day they were married, her mother wore black as if at a funeral.

Reggie was the cheeky, charming one who wanted to go straight for the sake of love; and Ronnie was the psychotic, slobbering hulk who messed everything up. At least, that’s the story of the film, which paints her as a fragile Juliet to Reggie’s Romeo. Real life is more complicated. She left him after two weeks and killed herself two years later.

“I want people to see her for what she was, not as Reggie Kray’s trophy wife,” said her niece Frances Shea last week, before seeing the movie. It was her bed that Frankie lay down on after taking pills. “My grandad witnessed all that and was heartbroken.”

The Sheas have tried in the past to have the body moved elsewhere, to distance Frankie from the Krays. But now she has become central to their story, thanks to an American director, Brian Helgeland, who won an Oscar for LA Confidential.

I’ve seen posters all the way to the cemetery, on the bus stops, at the train stations: Tom Hardy looking slick and handsome as Reggie, or big and frightening as Ronnie. Airbrushed, stylised representations of a new version of an old myth, not much to do with the dead carnation heads on their graves. But the twins always knew glamour was a cover for grim reality.

“They came from nothing and managed to create an image for themselves in a way that nobody else had done,” says Dr Ruth Penfold-Mounce of York University. “Most criminals become famous when they get caught and go to jail. They achieved it while they were still active.”

They put their steel fist in a velvet glove, she says, by running glamorous West End nightclubs that attracted stars such as Judy Garland and acres of attention from the gossip columns. Reggie would have been a very successful businessman on his own, but his brother was darker.

“Ronnie was very much into the gangster image, getting them to dress the same in suits with slicked-back hair. He wanted to live the gangster lifestyle in a way that he thought Al Capone did ... import it to Britain.”

Gentlemen criminals, a cut above the riff-raff. A force to be trusted in chaotic times. People bought it, as they went to jail for killing other gangsters. “They never hurt the public,” said their brother Charlie on the day their mother Violet was buried in August 1982.

That was the day I first came across them in the flesh, as a 15-year-old in my first week of work experience on the local paper. Vi’s boys were let out for the day, handcuffed to the biggest guards the prison service could find, to make the twins look small.

There were horses with black plumes as the hearse drove from her flat in Shoreditch a dozen miles up north to Chingford Old Church, with 60,000 people lining the streets. It was the kind of journey many of our families had taken, out of the old East End and into Essex for an escape from poverty to a bit of comfort, space and greenery.

The cortège passed the family home of a football-mad seven-year-old boy called David Beckham. We were both of us raised on the borders of an East End that still felt postwar. It was long before the Olympics.

We were raised on the milk of a myth: that we looked after our own; that the Krays were tough but they had manners; they were good to their mum and loved their dogs. Not like the new thugs. Not like the blacks and Asians colonising the old streets, some of our elders said, making no secret of their racism.

They were out of touch. Our school mates were black and Asian, and few of us could understand the appeal of the National Front. But I knew, as I stood among the crowds at the funeral, that part of the reason some people still had strong feelings for the Krays was because they were white. They represented something lost, even then.

They were twin symbols of an idea that stretched back to the so-called Spirit of the Blitz: the people of the East End running their own lives, working together, keeping their own code without interference from officialdom in any form.

They would not speak to a copper, as one character says in Legend, but they would kiss a gangster.

Diana Dors was at Violet’s funeral. So was Barbara Windsor. People came out to see the stars, but also because the Krays were still a force. They were still running rackets from behind bars, even providing bodyguards for Frank Sinatra when he came to Britain. So security was tight both ways, villains and coppers side by side for once, but my news editor had a plan.

“You’re a kid. You don’t look like a reporter. Put my jacket and tie on and go and join the queue of mourners, see if you can get into the church.” I’m still not sure if he was joking, but I went anyway, shaking with fright, wriggling my way through the crowds until I was at the back of the queue to get in. I hadn’t really thought this through, and now I was committed, there was no escape.

It was a hot day and I was sweating in torrents. We inched forward to the door of the church. Then a huge man in a suit and shades took a step forward in front of me, blocking the way. His arms crossed, he leant down and said very quietly in my ear, in a deep and threatening voice that gives me shivers to this day, “You must be fucking joking.”

I ran then – back into the crowd and through a hedge, feeling him close behind. By the time I got back to the news editor, I was a wreck. He laughed, and said at least I had tried. And when a job came up, I got it.

Meanwhile, the influence of the Krays was fading. Ronnie died in Broadmoor in 1995. Reggie was released from prison because of his cancer, eight weeks before he died in 2000. The crowds were much smaller for his funeral. Their generation was dying off.

My nan was part of it. She spoke in an accent that was a product of time and place but which has now vanished like her culture; a curious blend of Cockney and the received pronunciation she had heard as a child and a young woman, when the wireless was all they had.

The last time I heard that accent was when I went to interview Dame Vera Lynn last year. She was 97 but still clearly remembered driving through an air raid in a car with a soft top, wearing a tin hat for protection, to a recording studio in north London. She read the words, the orchestra played. then she recorded the song, just like that. “One take Vera, they called me, dear.”

It was “We’ll Meet Again”. I heard that song the last time I saw my nan, when we sang together, holding hands, along with all the other residents of the care home. She’s gone now. Her voice is gone. That communal spirit has gone, too.

As the East Enders moved out of London, made a little money and fell in love with Mrs Thatcher, community gave way to just immediate family and then to greed: the narcissistic culture of EastEnder Essex today, in which cheap fame and piles of dosh are all that matter.

They’ll love the flashy charm and swagger of Reggie in Legend. The twins would love that love, but the real East End they knew has gone. The Krays have passed out of reality into Jack the Ripper or even Robin Hood territory, their story can be anything a film-maker wants.

Still, there is a real woman lying in the grave. The remains of her, anyway. As dominated by the Krays in death as she was in life.

“If I could write the beauty of your eyes, and in fresh number, number all your graces …” says the poem on her headstone. At first, because of where we are, I take it to be sentimental tosh. But it’s not. It’s Shakespeare. Even his words are corrupted by the twins’ presence.

The poem is about immortality, which Frankie will achieve through Legend, and deeply sympathetic to her. It’s just another fantasy, of course. Poor Frankie.

The Krays created their own legend. But that cost lives, and here in the rain by Frankie’s grave, the legend feels like nothing but a tragedy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments