Laurel and Hardy: Two angels of our time

As 'Stan & Ollie' is released in UK cinemas, Martin Chilton reflects upon the duo’s astonishing impact on modern culture

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“If you don’t like Laurel and Hardy, you are no friend of mine,” said Star Wars actor Mark Hamill, one of millions of people who have been charmed and inspired by the greatest comedy duo of all time.

Their impact on modern culture is astonishing: they influenced artists, writers, musicians and actors – everyone from Alec Guinness to JD Salinger, from René Magritte to Samuel Beckett – and inspired a whole generation of comedians. Two admirers, Steve Coogan and John C Reilly, star in the new biopic Stan & Ollie. Coogan plays Englishman Stan Laurel and Reilly stars as American Oliver Norvell Hardy in a movie, written by Jeff Pope, about the duo’s ill-fated tour of the UK in 1953.

Laurel and Hardy have always had a special place in the affections of British comedians, and not just because Laurel is from the Cumbrian town of Ulverston (home to the charmingly idiosyncratic Laurel and Hardy Museum). He was born Arthur Stanley Jefferson but changed his name because he thought a shorter one would get a bigger slot on billboards, choosing the new surname after seeing a drawing of a Roman general, Scipio, wearing a laurel wreath.

After a long spell in separate acting careers, they made more than 100 short and full-length films together, many of which were shown regularly on the BBC in the 1960s and 1970s. Ricky Gervais, Frank Skinner, Stewart Lee, Al Murray, Jennifer Saunders, Paul Merton, Peter Kay, Matt Lucas and David Walliams were among those who became ardent fans after seeing them on television.

The Oscar-nominated actor Minnie Driver tells me: “When there were only three channels on TV in England, Laurel and Hardy or Harold Lloyd were the only things on BBC2 at six in the evening,” she says. “It was that limbo time between the end of homework and beginning of dinner. I initially watched because it was all that was on. However, I swiftly fell in love and with a child’s optimism always thought eventually things would work out well for Ollie and he wouldn’t get pied in the face/smacked in the face/ poked in the eye. As a child who loved dance, I quickly realised that that is what Stan and Ollie did – a weird, beautiful ballet of physicality and humour. I still watch them to this day and marvel at Stan’s quiet grace and Ollie’s perfect timing.”

Physical grace was certainly one of the qualities of a pair who were so different in physique. The dance scene in Way Out West, with the slim Laurel and 20-stone Hardy performing a soft-shoe shuffle-come-waltz, as the Avalon Boys sing “At the Ball, That’s All”, is one of the most life-affirming moments in cinema history. Skinner even went to the extreme of saying that new girlfriends were “subjected to the Laurel and Hardy test”, when he would play a video of that sequence. “If she didn’t laugh at them dancing, I instantly wrote her off as a future companion,” he admitted.

Peter Sellers, who took a poster-size autographed photo of Laurel with him wherever he travelled, modelled his character of the gardener Chance on Laurel for the film Being There. The star of Dr Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb would have been tickled to know that the British radar system to detect Russian nuclear attack in the early 1960s was secretly codenamed Laurel and Hardy.

Older fans will also remember the time in 1975 when one of their comedy songs from Way Out West, “The Trail of the Lonesome Pine”, reached number 2 in the British charts, pipped to the top spot only by Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody”.

It is not just the Brits who fell in love with The Boys, as they were known in Hollywood. Bette Midler said that when she gets together with fellow comedian Billy Crystal “we have a debate as to who was better, Stan Laurel or Oliver Hardy?” Steve Martin was such a fan of his “comedy heroes” that he seriously considered doing a film about them in which he took on the daunting task of playing both roles.

Hamill, though, would be hard to top as a passionate Stan and Ollie man. When he landed the part of Luke Skywalker in Star Wars, he used to travel to the set on his days off just so he could talk to Peter Cushing. “He was stunned that I knew he had appeared as one of the students in Laurel and Hardy’s 1939 movie A Chump at Oxford,” Hamill told The Ross Owen Radio Show. “‘Oh my dear boy, you have done your homework,’ he said. Peter told me that Stan was very different from his screen persona. He said between takes Stan would talk to the director about the framing of the shot and specifics of the gags, while Oliver would sit quietly reading a newspaper and talking golf with the crew. Laurel was like the de facto director and everyone would look to him for advice.”

There was another connection among George Lucas’s cast. After Laurel was given an honorary Oscar in 1961, four years after Hardy’s death, Alec Guinness wrote to Laurel saying, “for me you are one of the true greats ... one of my earliest ambitions was to emulate you.”

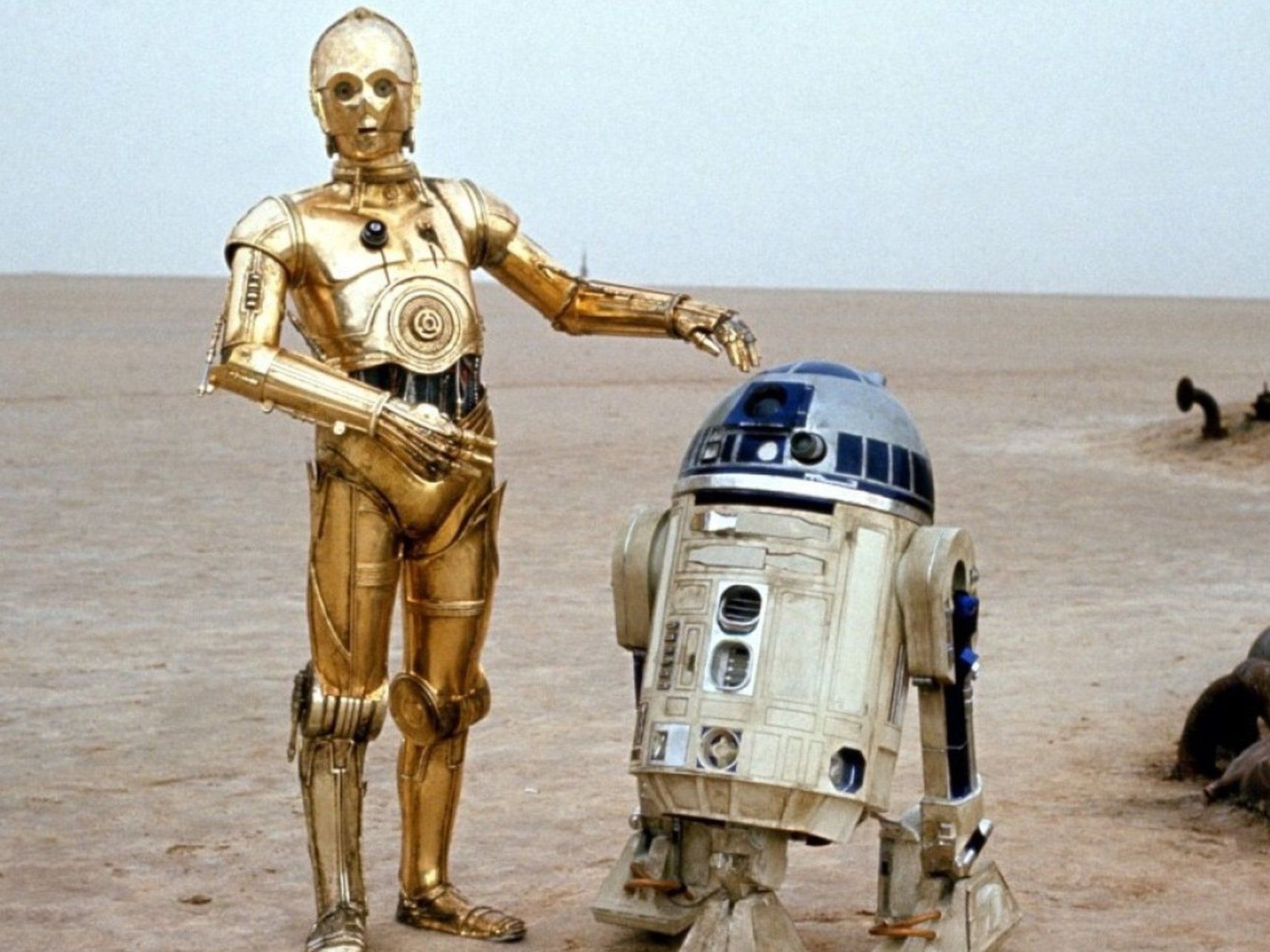

Hamill said one of the highlights of acting in Star Wars was being in scenes with the robots R2-D2 and C-3PO. “I was the straight man to them,” he recalled. “My impression is that R2-D2 and C-3PO were the Laurel and Hardy, the comedy relief, with one being the superior intellect and dominant personality, pushing around a more innocent friend.” Hamill said that when he first read the script to the 2015 sequel Star Wars: The Force Awakens, and saw that R2-D2 is switched off, he rang director JJ Abrams to complain. “One of my reservations, when I read the script, was that they were splitting up one of the great comic duos,” he recalls. “I said to JJ, ‘it’s as if you went to see a Laurel and Hardy film and Stan is in a coma’.”

Artoo-Detoo and his domineering gold friend are not the only double act inspired by Laurel and Hardy. The scenes involving Didi and Gogo in Beckett’s Waiting for Godot closely mirror scenes Laurel and Hardy created on screen, which is no surprise given the Beckett said he “never missed” their films. His absurd tragi-comic characters have so much of Stan and Ollie about them. When Mel Gussow compiled his book Conversations with and about Beckett, he said the Irish playwright admitted to being “tantalised” by the idea of what they would have been like performing a version of Godot.

Fahrenheit 451 author Ray Bradbury said that one of his happiest moments in life was seeing them on stage, while JD Salinger described them as “two heaven-sent artists and men”. Kurt Vonnegut, a master of written slapstick, said: “They were two angels of my time, I used to laugh my head off at Laurel and Hardy.”

So what exactly is it that makes them so great? There were low points in a film partnership that lasted from 1927 to 1951, but at their very best – with masterpiece shorts such Towed in a Hole, Tit for Tat and Big Business and longer movies such as Way Out West and Sons of the Desert – they created sublime and timeless works of art.

The Music Box, which won the 1932 Oscar for best short comedy, sums up the futility of much of human endeavour. It is a modern-day Sisyphus tale, as two men, totally unsuited for the task, have to move a heavy mechanical piano from the bottom of a steep hill to the top. Each time the piano slips away and goes bouncing back down the 147 steps you laugh as much as you cry. Do they succeed? Well, does Godot ever turn up?

They were the perfect pairing. Georgia-born Ollie always has echoes of the old faded southern gentleman about him, twiddling his tie as he yearns for order and dignity. He tries without hope to control the chaotic Stan. While Ollie twiddled, Stan fiddled with his hat and hair (singer Harry Nilsson used to do to do an impression of this to make John Lennon laugh) and, for both Stan and Ollie, tranquillity is forever elusive.

Hardy had a superb repertoire of close-up expressions: his eyes speak of his stoicism amid the despair. He called his “camera look” his “slow burn” – a way of registering disgust and frustration at Stan’s blunders. Ricky Gervais openly admitted in a previous interview “everything I’ve done I’ve stolen from them”, adding that Martin Freeman’s to-camera looks in The Office were modelled on the exasperated mannerisms of Hardy.

Hardy’s skill was no accident: it was founded on paying close attention to fellow humans. As a youngster, he had helped his single mother run a hotel. “I know Laurel and Hardy are dumber than anyone else,” said Hardy. “But I like to watch people. Wherever I travel in the world, I still am in the habit of sitting in the lobby and watching people walk by – and I tell you, I see many Laurels and Hardys.”

That everyman quality is one of the reasons their comedy is timeless and still popular with the many thousands of fan groups around the world who call themselves “Sons of the Desert”. Laurel and Hardy don’t rely on jokes per se, but on recognisable human situations that never change. “Laurel and Hardy are completely timeless,” Stewart Lee told The Independent in 1998. “It doesn’t matter that their films are old. They’re about power struggles in relationships, and everyone can relate to that. Laurel and Hardy will never not be funny because people will always be bickering with their partners or friends or colleagues.“

The person they quarrelled with most on screen was the character played by James Finlayson, who appeared in 33 of their films. Finlayson was just the sort of grim pedagogue who always lay in wait for the boys. The aggravation they cause him (particularly in the tit-for-tat destruction films) provoked memorable looks of rage from the stern, bald, moustachioed Scottish actor. Actor Dan Castellaneta said that when he and The Simpsons producers were searching for the best way to express Homer Simpson’s angst at the world, he remembered how Finlayson would mutter “D’oh!” when he was particularly frustrated by Laurel and Hardy.

On screen, Hardy was like the irresponsible father-figure to the more innocent Stan (who was also a model for Ardal O’Hanlon character Dougal in Father Ted) but off-screen their personalities were very different, with Laurel being the more serious professional. While Hardy was happy leaving his work behind when he left the set to go gambling or play golf (he was good, and won numerous trophies), Laurel was a workaholic, refining scripts and film takes long into the night. Both had chaotic love lives, with seven marriages between them.

Laurel told friends that part of the appeal of their cinema characters, who fight, cry, quarrel and destroy property in public, was that the pair unwittingly exposed social pretensions. Perhaps that is why surrealist artist René Magritte said he was such “an admirer” of Laurel, paying tribute to his look in the celebrated Man in a Bowler Hat painting.

Laurel had an interest in surrealism. Wrong Again was partly inspired by the films of Luis Buñuel and many of the sight gags in their films – eating their hats, being able to light a match with their own fingers, having a horse standing on top of a grand piano, being attacked by a gorilla while moving a piano across a narrow suspension bridge above the Alps – blended slapstick and surrealism. They are the only street musicians dumb enough to busk for money while playing “In the Good Old Summertime” during a snowstorm. Only Laurel and Hardy would try to be Christmas tree salesmen in August.

They were adventurous filmmakers, too. The idea of a custard-pie fight was old hat by 1927, so in The Battle of the Century they decided if they were going to have one, it would have to out-do all the predecessors. They bought 4,000 pies – genuine cherry, blueberry and banana ones – from the Los Angeles Pie Company and devised a stunning sequence which includes the sort of grandiose long shot that was later used in Gone with the Wind, when Scarlett O’Hara is surrounded by wounded soldiers. “It brought pie-throwing to apotheosis,” said author Henry Miller. “There was nothing but pie-throwing in it, nothing but thousands and thousands of pies.”

In the pantheon of movie comedians, Laurel and Hardy seem to hold a rank below silent film stars Chaplin and Buster Keaton, and have never received the scholarly attention given to that pair or to Harold Lloyd. Laurel worked with Chaplin during his early days on the British music hall circuit and deferred to the superior talent of someone he nevertheless believed was “a deeply unhappy man”. Stewart Lee is among those who believe that Laurel and Hardy have survived better than Chaplin, whose work does not “translate to the modern world”.

“Chaplin was a genius but he did not get as much pure laughter as Stan,” said actor Dick Van Dyke. “With Chaplin I can always see the technique showing but with Stan the technique never shows. Never. And that to me is proof that he is an infinitely better craftsman than Chaplin.” At Laurel’s funeral in 1965, a tearful Keaton said, “Chaplin wasn’t the funniest. I wasn’t the funniest. Stan Laurel was the funniest.”

Emmy-winning actor Stan Taffel, a film archivist and preservationist who has appeared in documentaries about the silent comedy era, is president of the Cinecon Classic Film Festival in Hollywood. He offers an explanation for their comparatively low status compared with their silent movie contemporaries. “The Laurel and Hardy films have never been treated with the same reverence as the films made by Chaplin and Keaton because, in part, much of their best work was in the short subjects they made and by the time they teamed up, two-reel comedies were not always held in the same regard as the full-length format,” Taffel tells me. “Reviewers of the time paid little to no attention to their work until they appeared in feature-length films. Chaplin and Keaton entered the feature-length market in 1920, a full decade before Stan and Babe made their first starring feature, Pardon Us (1931). By that time, they had made over 50 films together, virtually ignored by critics.

“Chaplin and Keaton are best remembered today for their classic features and not as much for their earlier work in two-reel comedies, that is, except by the ardent fans who have sought out these shorts. The other factor is that Laurel and Hardy’s two-reel films have more or less disappeared from television screens in any regular venue, making it harder for new audiences to experience their brand of comedy. With the rights to their films held by different companies, theatrical and television wise and uniquely held territory by territory, it is difficult to come to any agreement as to who has the rights for each exhibition. It seems everyone expects their share of the till, everyone except for the living heirs of Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy.”

There is no doubt they fell out of fashion in America for a time. One of the reasons they came back to the UK for that ill-fated eight-month tour in 1953-54 was that they were getting no work in Los Angeles. As Laurel lamented at the time, “Yesterday in Hollywood I was everybody’s host, today I’m nobody’s guest.“

One man doing his best to counter that is Ross Owen, the organiser behind the Laurel and Hardy Roadshow and the cinema screenings of their films in recent years. “Laurel and Hardy stuck by each other through thick and thin,” Owen tells me. “Nothing phased them. Whether they got soaked to the skin after falling into a pond or covered in soot from head to toe, they would always pick themselves up, dust themselves down and get on with their day. It was this special relationship that set them apart from other comedy teams of that era and that’s why they’re so beloved by their fans throughout the world to this very day. Kids saw themselves in them. Parent’s saw their kids in them. Laurel and Hardy appealed to everybody.”

Owen says that although the pair had “artistic disagreements”, it is certain that “Hardy recognised the creative genius in Stan and always trusted his judgement. They had a strong mutual respect for each other and there was never any jealousy between them.”

Although Stan & Ollie deals with one of the lowest times in their lives – both were suffering severe health problems and exhausted by the rigours of touring to provincial theatres up and down Britain – they remained resolute friends right up until Hardy’s heart attack ended their working life. “In their films, they suffer in such a dignified way. When things fall on their heads, they don’t really get annoyed. Stan will just rub his head and wait for the next thing to land on his head. I like that thing of just accepting your doom,“ said Lee.

Their catchphrase – “well, here’s another fine mess you’ve gotten me into“ – seems to sum up a pair whose friendship survives the severest trials. There is a warmth and companionship to them that is universal, something they even referenced ironically in the 1932 short Their First Mistake:

“My wife says I think more of you than I do of her?” says Ollie.

“Well you do, don’t you?” Laurel replies.

“We won’t go into that,” says a deadpan Ollie.

It is fitting that these accident-prone masters of incompetence got together because of a mishap. Hardy, who loved cooking, suffered third-degree burns on his arm when he was scalded while cooking a leg of lamb. Laurel came out from directing and started acting again while he recovered. Hal Roach had a moment of inspiration and saw what they could do together and teamed him up with Hardy when he returned from his injuries. “We got together on account of a leg of lamb,” Laurel said. “Everything seem to be by accident.”

Let’s hope the biopic Stan & Ollie helps entice a new generation into discovering their magical films. “Everything began and ended with Laurel and Hardy,” Gervais said. “It hasn’t really been improved on.”

Stan & Ollie is released in UK cinemas on 11 January

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments