Ken Loach on retirement and Keir Starmer: ‘It’s good for Labour to be seen to attack me’

The celebrated filmmaker behind ‘Kes’ and ‘I, Daniel Blake’ speaks to James Mottram about the culmination of his unofficial trilogy of films about modern Britain, his expulsion from the Labour Party, and who he’ll vote for come election time

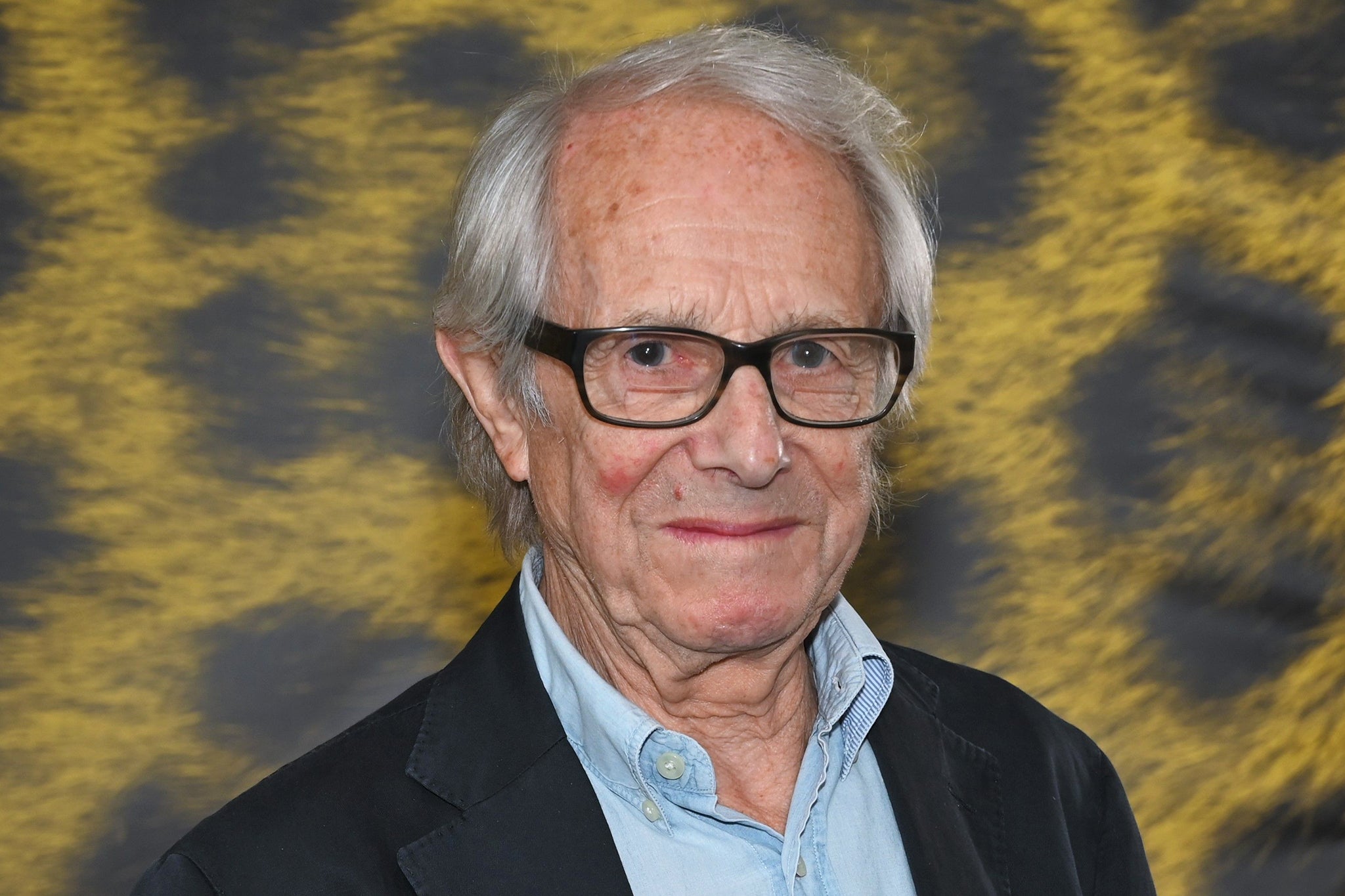

A decade ago, when Ken Loach was shooting his period drama Jimmy’s Hall in the northwest of Ireland, rumours spread that it would be the last film he’d ever make. The left-wing filmmaker behind Kes, Raining Stones and Riff-Raff, movies that defined the British working-class experience with humour and heart, was in his late seventies. Retirement wouldn’t be unexpected, and Loach did little to extinguish the notion. “Well, I was sinking in an Irish bog at the time,” the 87-year-old reflects today, cutting a studious-looking figure in his glasses and navy jacket. “Why am I, a man of mature years, losing my shoes in an Irish bog?”

After Jimmy’s Hall, though, Loach found his footwear again, so to speak. He followed it up in 2016 with I, Daniel Blake, a blistering look at the cruel and byzantine UK benefits system and the boom in food banks. It won him a second Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival (following 2006’s The Wind That Shakes the Barley), putting him in a very rarefied group of directors. Then came 2019’s Sorry We Missed You, a heart-wrenching swipe at Britain’s gig economy. Now, with The Old Oak, he’s completed an unofficial trilogy of sorts. And this one may actually be his last film.

Another hard-hitting study of Britain’s underclass, like its two predecessors, The Old Oak takes place in the North East, in a part of County Durham left decimated by pit closures and the miners’ strike in the 1980s. Or “monuments to the destruction of communities,” as Loach puts it. Like Liverpool, Manchester and Glasgow, working-class cities he’s set many a film in, he felt drawn to the region. “I’d always wanted to work there,” he says.

Again scripted by his ever-present collaborator Paul Laverty, the film is largely set around its eponymous run-down pub, run by TJ Ballantyne (Dave Turner). Riddled with unemployment and poverty, the area has also seen an influx of Syrian refugees rehomed there by the government. “Paul had read the first story of the Syrians arriving in the North East,” Loach says, sitting across from me in a conference room in a King’s Cross office. “So it began with Paul and then we talked about it and what ideas we would explore through the collision of the two communities.” Gradually, through TJ and Syrian photographer Yara (Ebla Mari), there is a coming together.

Compared to the likes of Loach’s social services drama Ladybird, Ladybird (1994), or 2002’s Sweet Sixteen, his Glasgow-set coming-of-age drama that gave Line of Duty’s Martin Compston his first major role, The Old Oak is one of the director’s more hopeful films, I tell him. He nods. “Hope gives you confidence, despair destroys you. And so there is that hope and it goes back to the strength of the miners’ strike. Eat together, stick together.”

The Old Oak isn’t the only recent film to tackle the refugee crisis. Agnieszka Holland’s Green Border and Matteo Garrone’s Io Capitano – which revolve around Syrian and Senegalese refugees, respectively, seeking shelter in Europe – both screened to rave reviews at the Venice Film Festival this month. Is there something in the air? “I wasn’t aware of the films, but I think there’s a broad opposition to the hostile environment,” he says. “Suella Braverman talking about ‘invasion’… [the country] being ‘invaded’ by small boats.” He also cites Robert Jenrick, the Minister for Immigration, ordering the painting over of Disney cartoons at a reception centre for the children of asylum seekers. “Disgusting man. Who would do that in their own right mind?”

I better not name anyone or I’ll be in trouble and it’ll hang around my neck. I think people can read between the lines. If Jeremy were to stand, I would certainly vote for him or someone with that background, absolutely

How does he feel when he hears of such things? “Well, you fight back,” he says, bluntly. It’s something he’s done his whole career. After studying law at Oxford, he began working for the BBC in the Sixties; his 1966 homelessness drama Cathy Come Home “hit the headlines”, as he modestly puts it – so much so that it led to a change in the law, meaning homeless fathers could stay with their wives and children in hostels. Three years later, he made the classic Kes, about a boy and his kestrel, but remained largely confined to television over the next decade.

In the Thatcher era, he rubbed the establishment the wrong way, making documentaries like A Question of Leadership, about the 1980 steel strike – which came under attack by the Independent Broadcasting Authority for being “unbalanced”. It was only in the 1990s that he returned to film, winning the Jury Prize in Cannes for 1993’s Raining Stones, and shortly afterwards meeting Laverty, the writer who has been a near-constant by his side ever since. But the more visible Loach became, the more open he was to criticism.

Those critics have included the Labour Party. Loach has had a turbulent relationship with the party, previously turning in his membership in the Nineties in protest over Tony Blair, then rejoining once it was led by Jeremy Corbyn. But under his leadership, Labour was engulfed by an antisemitism row, with a 2020 report by the UK’s equalities commission finding that under Corbyn’s leadership the party “did not do enough to prevent antisemitism and, at worst, could be seen to accept it”. In 2021, as part of new leader Keir Starmer’s crackdown on antisemitism, the party expelled Loach for his support of organisations purged by the party. The Corbyn-supporting groups included Labour Against the Witchhunt, which claimed the antisemitism allegations were politically motivated.

“What’s changed in the last few years was the political climate,” Loach says. “Because when Jeremy Corbyn became leader of the Labour Party and a lot of people supported him… I was known to support him… but then the attacks came, and the right wing attacked him. And they also attacked people who were associated with him. And some people ran for cover, and others stuck with him.” That Loach also spoke out about Palestinian rights didn’t help, he feels. “Put the two together, and they’re going to attack you.”

In July, Labour shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves was challenged by The Guardian’s Simon Hattenstone on whether Loach’s views automatically make him antisemitic. “You don’t think Ken Loach is antisemitic?” she replied. “OK. Well, I think we might have to agree to differ.” Asked why she believed Loach to be antisemitic, Reeves said: “Look, I’m not on the bodies that make these decisions, but I think it’s right we have a zero-tolerance approach [to antisemitism].” Further asked whether it’s right to make an accusation without supporting it, Reeves repeated: “Well, look, I’m not on the body who makes these decisions.”

Loach claims Labour’s leadership targeted him as a signal to “the establishment” and voters to the right. “I think they reckon that they get points by attacking me like that,” he says. “Now the people they are looking to for support… they’re not looking to people like me for support, or people on the left or traditional Labour voters. They’re looking to the establishment. So it’s good for them to be seen to attack me because the establishment will back them up. “It’s very distressing,” he continues. “But I think they rely on that. They want to cause as much political and professional damage as they can and personal distress. They want to take you out, basically.” (Labour declined to comment on Loach’s statements.)

Does he hold any hope for Keir Starmer leading Labour to an election victory? “I’ve no hope for Starmer at all,” he says. “I mean, I think he’s a real political vacuum. There is a political vacuum on the left, because he’s moved to within a cigarette paper of the Tories. I mean, the whole 2017 program [by Corbyn] has been wiped out of public discourse. You think what it was; it was public ownership, kicking out the privateers from the health service… I think he promised to take energy back into public ownership. Social justice, economic justice.” Starmer has, he says, “torn up everything he said. Predictably. So I’ve no hope.”

I ask how he will vote at the next election. “Personally, I can’t vote for Labour and Starmer,” he says. “I would find the least damaging candidate. And I think there’ll be one or two who will be less damaging. For sure.” An independent candidate? “I better not name anyone or I’ll be in trouble and it’ll hang around my neck. I think people can read between the lines. If Jeremy were to stand, I would certainly vote for him or someone with that background, absolutely.”

For years, the Nuneaton-born Loach has lived in Bath with his wife Lesley, mother to his four grown-up children, including filmmaker Jim Loach. “I’m kind of lucky,” he says. “I lead a middle-class life, I suppose, given the business I’m in.” How does he keep in touch with younger generations? “We’ve got grandchildren who are in their late teens, mid-twenties now. They and their friends are very bright and aware – much more aware than an old octogenarian is – of things that are going on, and I look to them for a clue on what’s going on in that generation.”

Even approaching 90, Loach is still engaged – he is knowledgeable, for example, on the “Barbenheimer” phenomenon of early summer. “I went to see Oppenheimer because I know Cillian [Murphy, its star]. We worked together [on The Wind That Shakes the Barley]. He’s a lovely man and I have great respect for him. A brilliant actor. Very modest and just normal… very easy to work with. And just one of the gang.” And Barbie – did he see it? “No. I didn’t treat myself to Barbie!” he chuckles.

Judging from the themes of his films, the soft-spoken Loach seems like he carries the weight of the world on his shoulders. I wonder how he unwinds. Does he watch reality TV? He screws up his face. “I can’t watch reality TV.” He likes Have I Got News for You and Antiques Roadshow. “I watch that from time to time, though I’m disappointed… there’s far too many trinkets and war memorabilia,” he says. “I look for a decent old chair now and then if it comes on.” He even made an appearance on the show a few years back – he took a pewter ashtray to be assessed. “I like seeing enthusiasm for old things.”

I’m curious to know if The Old Oak will truly be his final film, or whether he could do a reversal, like on Jimmy’s Hall? “I mean, I can’t see it at the minute,” he says. “The physical and emotional energy and commitment [required] and just keeping everyone buoyant [is a lot].” And anyway, there’s lots to keep him active, he says. “Films are a joy. But once you’re connected to politics, it’s hard to avoid taking part. The left has such potential, so many good people. To bring it together… if you could contribute to that, that’d be really something worth doing.”

‘The Old Oak’ is in cinemas from 29 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks