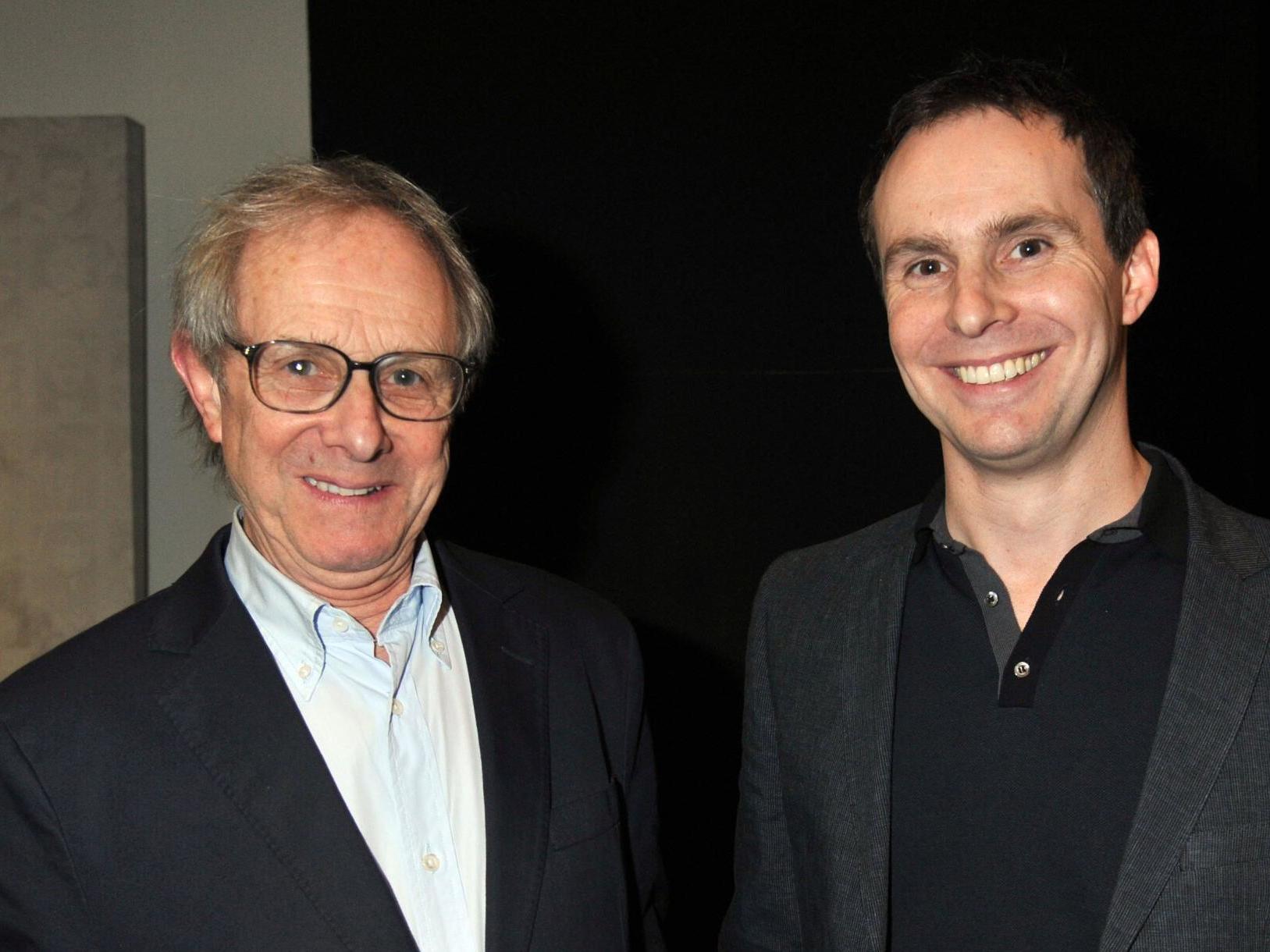

Like father, like son: Ken and Jim Loach on filmmaking, grief and the problem with Keir Starmer

To mark Father’s Day, the two directors talk to Ellie Harrison about 50 years of friendship and football, responding to antisemitism accusations, and trying to be a Tory in a socialist household

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I know this sounds very strange,” says Jim Loach, “but when I was little I thought Ken Loach was another person. I would read stuff in the newspaper or hear the name on television, but I didn’t think it was actually my dad.” Loach junior, an established TV and film director in his own right, is talking about his famous father from his home in north London. Later, I’ll catch up with the 84-year-old director of Kes and I, Daniel Blake himself. I had planned to talk to them together, until they said they’d probably just take the piss out of each other and I’d get better interviews with them separately. So here we are.

When Jim was born in the spring of 1969, his father was fast becoming one of the country’s most influential auteurs. His tour de force, Kes, a heartrending study of a young boy coming of age in the harsh surroundings of a Yorkshire mining town, was set for release. And his groundbreaking homelessness drama Cathy Come Home had aired three years earlier, sending shockwaves through British society. Over the course of his career, Ken has made 27 films and become one of the world’s best-known socialist filmmakers.

Ken and his wife Lesley were bone-weary but full of joy in the Sixties, living in a terraced house on London’s Highgate Road when Jim arrived, joining his brothers Stephen and Nicholas and sister Hannah. Emma, the last of the Loach children, came three years later, completing what Ken describes as a “handful” of offspring who were all “exasperating and delightful in equal measure”.

One trained as a solicitor, another as a pianist, but in spite of Ken’s best efforts to persuade Jim otherwise, he became a filmmaker like his father. His first directing job was Coronation Street in 2000, and after working on shows such as Hollyoaks and Shameless, he made his first feature film in 2010 – Oranges and Sunshine, a harrowing drama about the British orphans who were secretly shipped to Australia in the 1900s, and the abuse they were subjected to when they got there. Since then, Jim has directed episodes of Victoria, Tin Star, Deep Water and Lennie James’s gritty masterpiece, Save Me.

Jim admits he did not think highly of the film industry when he was a child, because it was forever taking his father away from him. “I remember Dad either being around all the time or disappearing off to make films,” says the 51-year-old. “I absolutely hated that. My mum said I used to hide his shoes to persuade him not to go.”

But when Ken was at home, he was a lively presence. Jim’s first memory of his father is of one of his mystery tours – “sometimes unkindly dubbed misery tours” – which involved the young dad whisking his children around London, telling stories about arcane places along the way. Sometimes they’d ride by double-decker bus, other times by tube, plumes of cigarette smoke twirling around them. It was the Seventies.

When Jim was five, the family moved to Bath, where Ken still lives. His father took him to the football every week, often to see “perennial underdogs” Bath City. “When I was about seven,” says Jim, “Dad would send me on to get an autograph from the players. It was for him – I wasn’t that fussed. But he didn’t want to ask himself.” After becoming a shareholder in a fan buyout, Ken was named as the club’s president last year.

While Lesley ran the house, Ken was intimately involved in the children’s academic lives and what they were reading. A huge amount of literature would come home with him every day. “Newspapers, pamphlets and political leaflets came in by the truckload,” says Jim. “Everything from Private Eye to The Morning Star.” Ken has 10 grandchildren now and he bombards them with books. “My eldest got Trotsky’s autobiography last week,” says Jim. “Ah yes!” says Ken. “The best book in the English language.”

The Seventies were mostly happy years, but they were tainted by a crushing grief that knocked the family sideways when Nicholas died. Jim was just two when his five-year-old brother was killed in a car accident. It was 1971, and Ken was driving on the M1 when a vehicle in another lane lost a wheel and forced his car into a bridge. Nicholas and Lesley’s grandmother died in the collision, and Lesley was left fighting for her life. Loach and his eldest son Stephen were injured, but not severely. The director didn’t work again for over a year.

“It devastated us,” says Ken, his voice quiet and brittle when speaking about Nicholas. “It changed everyone’s lives forever. It’s difficult to touch on something that is so profound and so morose in a few sentences, because there’s a danger it will become a cliché. Of course, a death is never that for any family. It’s not only very cruel, it’s harsh and destructive, and it has a terrible effect on everyone involved. He was an absolutely delightful little boy. To lose someone so significant in the family – it just leaves everyone bereft. Sometimes things are buried for many years and it’s very damaging. It’s a lifetime’s work, really, to come to terms with it. It’s something you don’t recover from, nor ever want to recover from, actually. I don’t want the waves to close over, not at all.”

While Jim doesn’t have any memories of his brother when he was alive, he remembers the aftermath of his death. “It is still a very potent and difficult area for the whole family,” he says. “Obviously, it casts a very long shadow and the ramifications are big. More recently, we got into a much better place about it all – just restoring his memory to its rightful place as part of the family story, and being able to talk about it, that’s what makes the difference.”

The first film Ken made after losing his son was Black Jack, an adventure set in 18th-century Yorkshire and the director’s one and only children’s movie. He went on to make dramas The Gamekeeper and Looks and Smiles, and following Margaret Thatcher’s election victory he directed the documentaries A Question of Leadership (1980) for ITV and Which Side Are You On? (1984) for Channel 4, both of which were deemed too political and banned by the very same broadcasters that commissioned them.

Jim was a teenager at the time, and he remembers experiencing a healthy dose of adolescent embarrassment over his father’s political zeal. “Going to school with ‘Support the Miners’ on my lapel in the early Eighties wasn’t the easiest choice to make,” he says, laughing. “And whenever my parents came into school I would be a little wary, because Dad would always challenge the teacher’s interpretation of the subject, which was anxiety-inducing for a teenage boy. I just wanted the ground to swallow me up.”

Whatever debates were happening in the classroom were most certainly happening at the Loach dinner table, too. Ken insists their home was “no intellectual powerhouse, it wasn’t a Bloomsbury circle, I promise” and claims conversations were more likely to be about football and daily domestic life than politics. Jim remembers thing slightly differently. “Gosh, this is going to sound so up itself,” he says, “but politics was always centre. Discussion was always wanted – it was what we were there to do. But obviously there was normal family life as well, it wasn’t like the United Nations.”

The Loach family would debate “pretty passionately” when Jim and his siblings were teenagers, but in a quiet and considered way. “It’s become shoutier as we’ve all grown older and wine has become involved,” says Jim.

Was Ken eager to instil his socialist values in the children? “It may seem hard to believe but he really let us find our own politics,” says Jim. “Obviously plenty of left-wing literature came into the house, so there were a lot of opportunities for radicalisation.” That said, Jim did flirt with becoming a Tory for six months. “God knows why,” he says, laughing. “I had the flag, I had some literature. I had a poster and everything – I think I put it up in the house. I don’t remember Dad asking me to take it down, surprisingly. I definitely would if it was my kids.” Ken has no memory of the Conservative phase. Perhaps he blocked it out.

“Jimmy was the one who made us laugh most, and he still does,” says Ken. “He’d always be doing daft things, sometimes consciously, sometimes without realising, which of course is much funnier. He’s the one you’d ask to go and fetch a left-handed screwdriver.”

In his teenage years, Jim wanted to be a journalist. He even made a pact with his sister Emma – who also later went into filmmaking – not to enter the same industry as their father. Ken had gone to a lot of effort to keep his professional life at arm’s length from his family, but that was hard, especially during the Thatcher years when his documentaries were banned. “It was financially difficult, of course,” says Ken. “I had to face leaving the business at one point.” He recalls the children writing to Channel 4 on his behalf, to persuade the broadcaster to air his documentaries. “It was great family loyalty,” he says. “They didn’t tell me, they just sent it. I was very touched by that. But it didn’t change anyone’s mind at Channel 4.”

Jim remembers his father seeming as though he had “the weight of the world on his shoulders” in the Eighties. “He’d bear it in a quiet way but it would be written all over his face,” he says. “I wish I had understood it more as a teenager, to be honest.” Ken resorted to filming a couple of adverts around that time, which no one was allowed to mention. “If they ever came on the television, we just had to look away or change the channel,” says Jim, chuckling. “Obviously now, looking back, it doesn’t matter. He did what he had to do to survive.”

Ken tried to dissuade all his children from pursuing a career in film. His own father, an electrician from a family of 10 who lived through the Great Depression, was “devastated” when his son went into theatre after university as he didn’t think it would bring financial security. When Ken himself became a father, he felt the same. “I had enormous luck,” he says. “I knew the odds of someone getting the same breaks as me were almost nil. It’s a very cruel business, film and theatre, very cruel. If you don’t make a success of it, no one wants to know you.

“You meet so many talented, intelligent, sensitive, thoughtful, generous people who should have a much better life than they do, but they get stuck and depressed because rejection is always the probable outcome. There are fleeting moments of satisfaction but long periods of uncertainty. People get to middle age and they just feel their lives are gone. That’s what I didn’t want the children to face.

“Anyway, Jimmy went into it and it turns out he’s very good at what he does. He’s a good professional, which is underrated, and he has empathy and a sensitivity to relationships. He’s done really well. I wouldn’t say it to him, though, because we take the mickey out of each other.”

Ken started out in the days when directors could stick with a producer and writer for years, or even a lifetime in the case of his collaborator Paul Laverty. In Jim’s era, however, broadcasting executives hold much more of the power, and directors are like “taxis in the rank”, according to Ken, making it harder for them to find their own voice. “The fact Jimmy has survived is extraordinary,” he says. “I wish he’d had the same luck as I’d had.”

Jim might not have had luck on his side, but he has had the support of his father. Ken is there with words of encouragement when Jim loses his nerve ahead of a shoot. And while Jim’s filming, Ken texts him “almost every day just as I’m about to start, with some suggestion or idea”. Sometimes it’s useful and sometimes you have to ignore it, Jim says, “because that’s what sons do, and he’s not always right, obviously.”

What’s more, Ken and Jim have very distinct directing styles. The kitchen sink realism of Ken’s films, from the 1967 adaptation of Nell Dunn’s Poor Cow to Riff-Raff to I, Daniel Blake, often involve improvisation and street-casting. While Jim shares his father’s flair for emotion and verisimilitude, he came up through the ranks on traditional series like Coronation Street, where spontaneity was not encouraged. In fact, Ken’s advice nearly got him fired from the soap. Jim was filming a scene where a character stood on a desk and ranted at his bosses about the injustices in his workplace, and Ken suggested that Jim ask the actor to improvise. “You can imagine how it pressed all my dad’s buttons,” says Jim. It wasn’t long before Jim was called up to the producer’s office at Granada. “She said, ‘We’ve been making Coronation Street for 50 years, and we’ve never improvised the show. And we’re not going to start now.’”

The supportive dynamic between father and son goes both ways – and Jim feels protective of Ken, who has long-been a polarising figure. In 2006, one critic said of his film The Wind that Shakes the Barley, a powerful indictment of British colonialism set during the Irish War of Independence: “Why does Ken Loach loathe his country so much?” Another compared him to Leni Riefenstahl, the Nazi propagandist filmmaker.

In recent years, Ken has been branded a racist, a misogynist and an antisemite, among other things. His support for Jeremy Corbyn and his pro-Palestinian stance has only encouraged yet more abuse. At the 2017 Labour conference, Ken landed himself in particularly hot water when he appeared to imply Holocaust denial was tolerable. He strenuously denied this in a letter to The Guardian, writing: “In a BBC interview, where speech overlapped, my words have been twisted to suggest that I think it is acceptable to question the reality of the Holocaust. I do not. The Holocaust is as real a historical event as the Second World War itself and not to be challenged.”

“The people I’ve worked with on political subjects have stuck their head above the parapet,” he says now. “Of course, if you speak up, people will attack you. I’m happy to defend all the ideas I’ve put forward in an open debate, in a fair discussion anywhere with anyone, but it’s the accusations that I find depressing. They’re lies.

“It’s immensely distressing for the family. And often leading the charge will be papers like The Guardian, bizarrely, who open the door for the foulmouthed abusers they know will follow. Or the BBC.

“The dishonesty, the abuse, the lies – they’re dangerous. It’s dog-whistle politics. And there are idiots out there who will act on the hatred that’s being generated. We’ve been pushed around in the street when one of the kids was having treatment for cancer and lost her hair, two blokes came up, one tried to push me into a corner. They shouted. We’ve had letters to the house, death threats, there’s stuff going to grandchildren. I mean, I’ll say what it is – it’s the pro-Israeli faction who will not tolerate discussions of that political tendency.”

Jim finds the online vitriol about his father very difficult to read, and has tried fighting his corner in the past. “It’s sort of impossible,” he says. “You can’t police the world. On the few occasions I’ve tried to, it doesn’t end well. There are one or two supposedly liberal political commentators who I have the least respect for, because they’ve written things they knew were untrue and it blows the whistle for the online trolls. They stand back and watch it happen as if their hands are clean, but really they’re the ones who started it because they knew what they wrote was incorrect and a complete inversion of the truth.

“I’m sure any son or daughter is going to want to look out for their parents, and it’s much harder when anyone gets to write whatever they want about them.”

For every person who reviles Ken Loach, there is another who adores him. He has won 104 awards over his six-decade career, including a Bafta and a Palme d’Or for 2016’s I, Daniel Blake, a staggering drama about Britain’s broken benefits system. His 27th film, Sorry We Missed You, came out last year to enormous acclaim, with critics hailing his damning takedown of the UK’s gig economy as “ingenious and devastating”.

Zero-hours employees have been extremely adversely affected by coronavirus, with many at higher risk of exposure or left with no income due to decreased demand. Ken has been following the government’s response to the pandemic avidly. “Oh god, where do you start?” he says. “It’s been absolutely buffoonish, grotesque incompetence from the moment the problem surfaced in China. Our politicians are like rabbits in the headlights. The failure to take action early enough, to provide protective equipment, to test – the incompetence just shrieks at you every day.”

Labour leader Keir Starmer’s approval ratings, meanwhile, are ever-rising. But according to Ken, he has been useless. “There have been all these open goals for the Labour Party,” he says. “Just stick the ball in the effing net, for Christ’s sake. I’m waiting for Starmer to mention the gig economy workers. When is he going to demand that every worker is given trade union rights from day one? When is he going to demand the end of the privatisation of the social care service? You’ve got care workers on zero-hours contracts who are visiting people’s homes – they’re not paid for their travel time. As we showed in the film, they get a 20-minute appointment, are paid a third of the minimum wage for the hour, £3 or less, then travel 40 minutes and then get paid. And they’re on the frontline, and risking their lives, and have no protective equipment, for £3 an hour. No one is helping them. The incompetence of this new Labour leadership really is shocking. Shocking.”

The current crisis feels like perfect fodder for Ken’s next film. “I don’t know,” he says, sighing softly. “At some point I’ll have to hang up the viewfinder.” Jim, meanwhile, is working on a script with Rona Munro, the writer of Oranges and Sunshine, who also collaborated with his father on his 1994 film Ladybird Ladybird.

“I always imagined I’d grow out of the feeling that when I show Dad something I’ve made, it’s like showing him my homework,” says Jim. “But I haven’t – and don’t think I ever will.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments