Acting’s last great character – John Standing on Elizabeth Taylor, Cary Grant and the day Peter O’ Toole dragged him off to a nunnery

The veteran and wickedly irascible thespian is a pukka former RAF pilot in ‘The Great Escaper’. In an outrageously indiscreet interview with Jasper Rees, he shares his stories of being caned at Eton, acting naked, wild nights with ‘Larry and Vivien’ and a cult appearance on ‘Game of Thrones’ – ‘I loathe that cr**!’

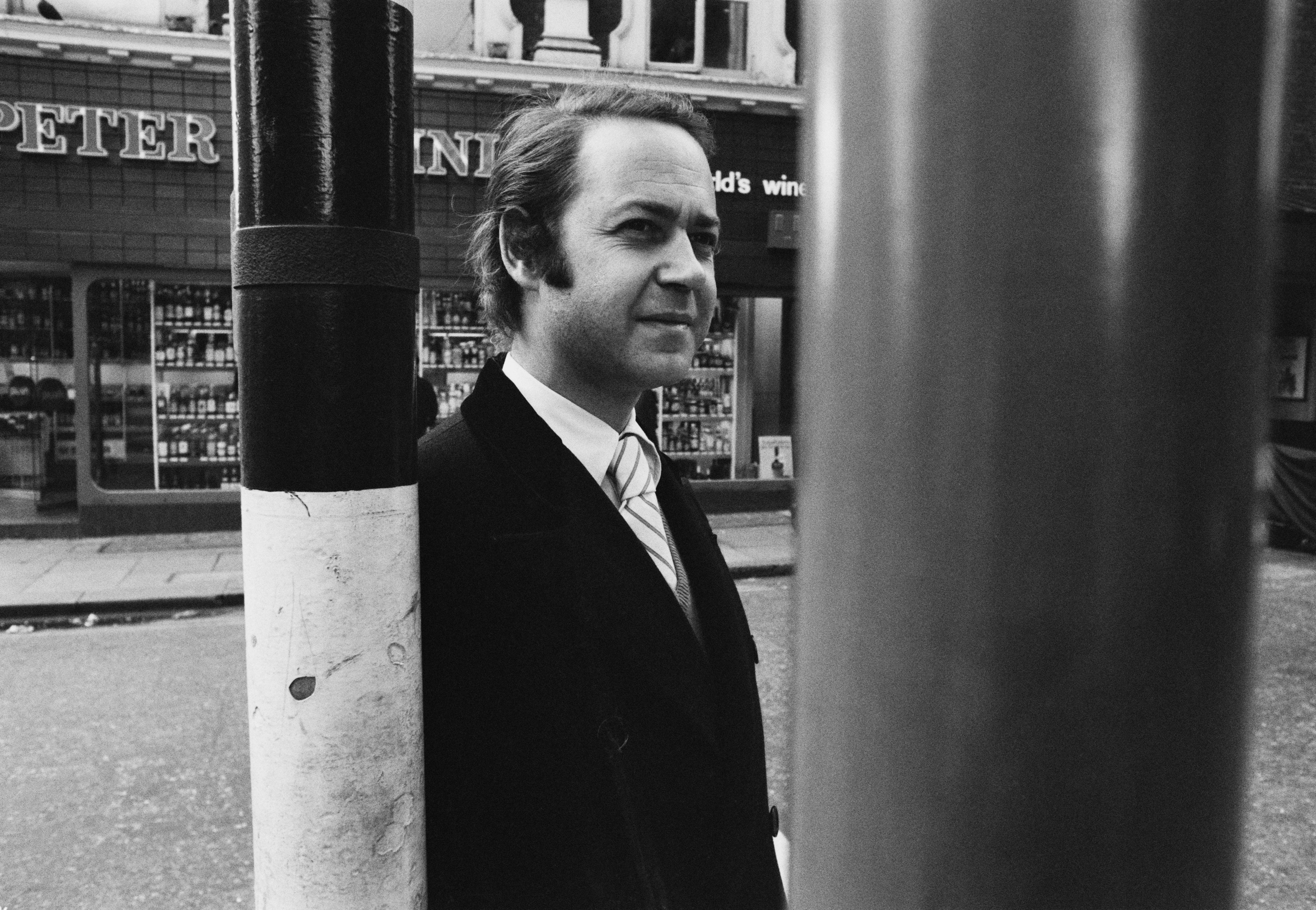

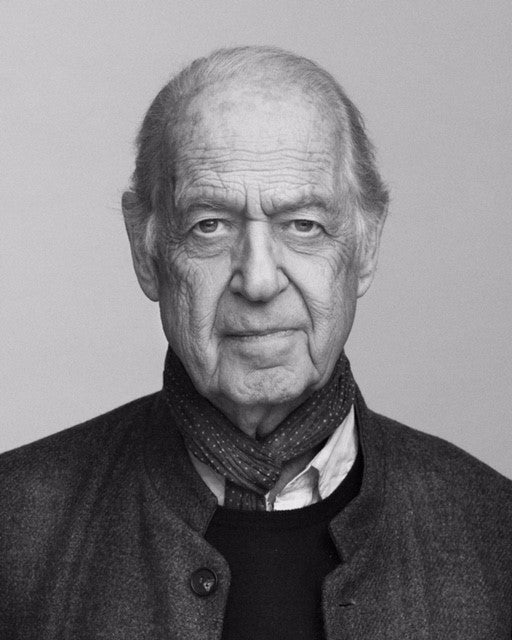

To meet John Standing is to glimpse a vanished world. He’s 89 and he seems to have shared a stage or a screen with everyone who was once anyone. There can’t, for example, be another actor left alive who has worked with both Vivien Leigh and Elizabeth Taylor.

“They were marvellous women,” he proclaims. “Staggering beauties, both completely different. Vivien was like a wonderful porcelain doll but somehow ravishing. She was very withdrawn. Elizabeth Taylor was much more earthy and outwards. She used to drink bullshots at lunch every day. She was ‘here I am, tits and all, look at this’.”

You may not think you know John Standing, but you do. Onstage a light comic actor who excelled in Coward and Wilde, on screen he was and still is perennially cast as plummy establishment types: a vicar in The Eagle Has Landed, a doctor in The Elephant Man, a bishop in V for Vendetta. (His camp hairdresser in X, Y and Zee with Taylor was an exception.) And now he’s a pukka former RAF pilot in The Great Escaper.

Oliver Parker’s touching film fancifully reconstructs the story of Bernard Jordan, who in 2014 famously snuck out of his care home to attend the 70th anniversary of the D-Day landings. The lead is played by Michael Caine, his wife by Glenda Jackson in her final performance before her death in June. Standing plays a veteran, still haunted by his role in carpet-bombing Caen, and has a powerful scene in which he admits to being an alcoholic.

“I consider myself bloody lucky to have got a gig like that one,” he says. “Michael is the biggest movie star we’ve ever produced. I’m not a movie actor.” Indeed, Parker cast him on the memory of a West End performance of Noël Coward’s Hay Fever in 1992. “Really peculiar,” he muses. “I don’t think it was very good.”

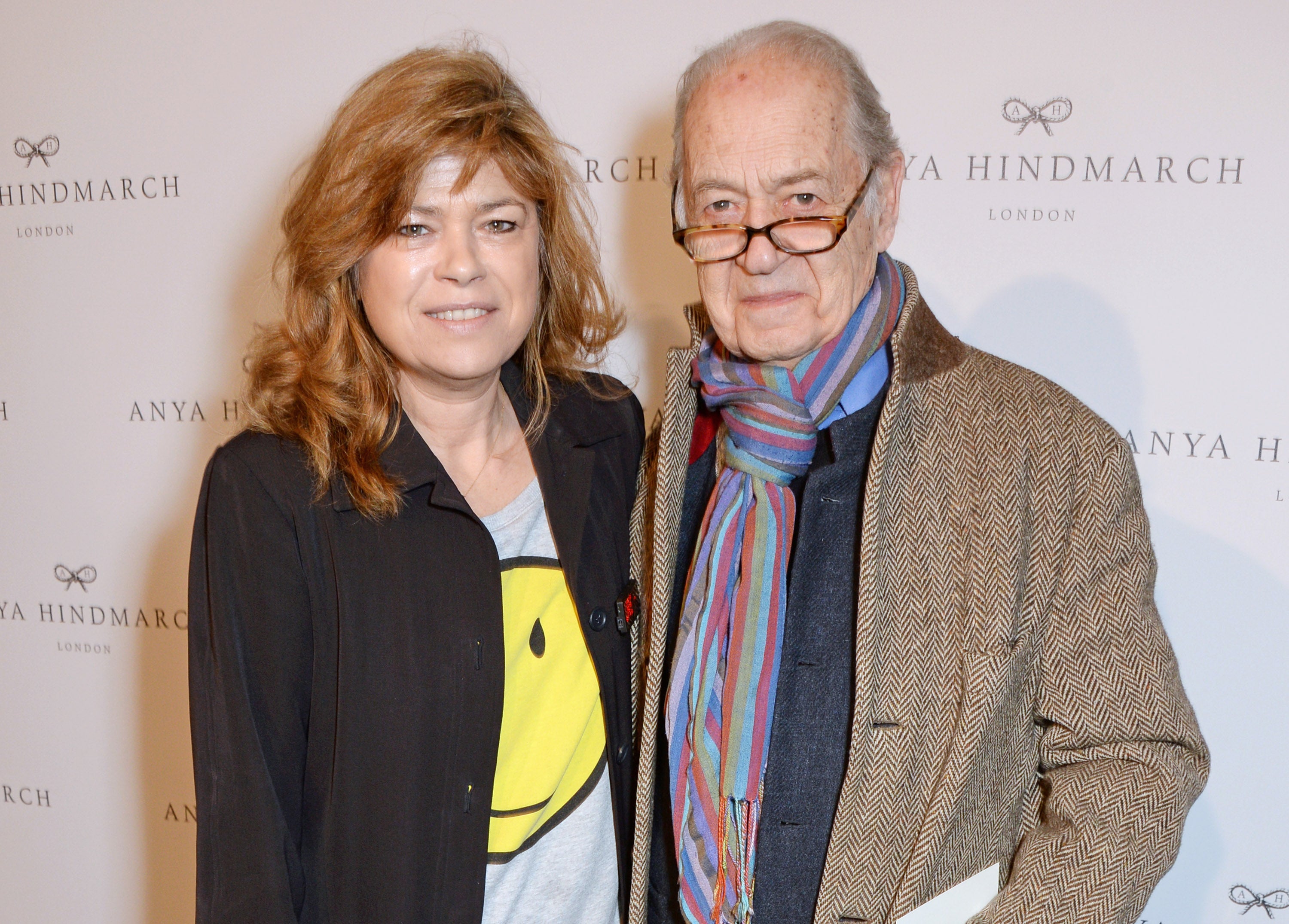

We meet at Standing’s home in Pimlico. On the walls of a beautiful open-plan main room are photos of the Rat Pack, his old mucker Peter O’Toole, his father-in-law the director Bryan Forbes. Standing and his second wife Sarah have three children, all now in their thirties. So he was an older dad. “You’re not kidding!” he says. On his right wrist is a thicket of friendship bracelets, at a guess gifted by grandchildren. Have they all kept him young? He certainly seems trim and spry as he bounces upstairs to a cosier room dominated by an easel, a piano, books, a massive TV and many of his own delicate landscape paintings. He plonks himself down on a modest day bed. “Sarah sleeps in the master bedroom and then I go and visit her from time to time,” he confides. “I sleep up here mainly because I’m a television addict.”

Does he ever watch himself on it? “What for?” he says, puzzled. He was in The Crown as an eccentric gent who sells his leaky Scottish castle to the Queen Mother, but he stopped watching after the first season. The controversy surrounding the most recent season – specifically the suggestion that Prince Charles plotted to dethrone his mother – means “really nothing” to him. In fact, the plotline involving the Waleses barely registered. “I saw in the newspapers a really pretty blonde girl playing Diana with a strange name.” He’s got no time for Game of Thrones in which his death scene as Lord Jon Arryn was cut and only his performance as a corpse with painted pebbles for eyes remained. “I loathe that sort of crap. I can’t bear it. And I get fan mail from people saying, ‘Please can I have your autograph?’ Fan mail for a corpse!”

And I get fan mail from people saying, ‘Please can I have your autograph?’ Fan mail for a corpse!”

As we leaf together through the pages of his memory, ghostly voices pour out through him. “I don’t get the girl and I’m not going to do it again!” he remembers Cary Grant telling him on set. Grant’s entire career was built on playing romantically successful men. His final film was Walk, Don’t Run, a romantic comedy set in the 1964 Olympics in Japan. For something to talk about one misty morning in Yokohama Harbour, Standing mentioned Cole Porter, whom Grant had played. “And I said, ‘I know Porter went both ways,’ and Cary said, ‘I was accused of going both ways and I never did and I never have! I have always been girl crazy.’ I thought, this is so strange. I’ve only been working with him for four or five days and he suddenly revealed all this.”

Then the unmistakable voice of O’Toole is exhumed, poking his head round the door of Standing’s dressing room at the RSC in the mid-1970s. “You’re a very funny man. I want to do a gig with you.” The gig, for BBC Two, was Rogue Male, a Thirties thriller about an attempt to assassinate Hitler adapted from a novel by Geoffrey Household. They went to O’Toole’s place in Ireland intending to rehearse. Mainly they smoked weed in the pub, O’Toole having forsaken alcohol. “We never opened the script once in two weeks. Not once. One day Peter said to me, ‘Johnnie, have you ever f***ed a nun?’ And I said, ‘Mm, I don’t think so, no.’ ‘Well we’d better go to the nunnery.’ So we went to the nunnery and of course we didn’t do anything of the kind. But a nun got on a table and sang a disgusting verse of The Sound of Music.”

Then, in 1976, he toured Australia with O’Toole in a detective comedy called Dead-Eyed Dicks. “It sounds bad and it was bad but we had more fun than any two actors probably have ever had. We went shark fishing and when he cast out he caught an albatross, which is deeply unlucky. ‘Bring that f***ing bird here, we’ll eat it!’” Did they? “No, course not!”

Though he has tended to play well-to-do types, Standing is proud that he “started life just like everybody else with nought but three farthings”. His parents were divorced and he rarely saw his father, Sir Ronald Leon, an alcoholic stockbroker who drank away his wealth. In 1964, Standing inherited £60 and a baronetcy. “I never use it ever, ever, ever. It’s nothing to do with what I do at all. I’m just Johnnie Standing.”

He got his professional name and his thespian leanings from his mother’s side of the family. He didn’t know much about his grandfather, knighted for war service, who was fatally bitten by a black widow spider in Malibu. One day, Standing was in a Dublin hotel when he spotted Fred Astaire, who invited him to breakfast. “He talked about my grandfather. He just said he was very popular in Hollywood in the 1930s.”

Standing’s mother Kay Hammond was an actress who for three years in the war originated the role of Elvira in Blithe Spirit. Her son would pitch in backstage with the play’s poltergeist finale. “I used to help with a stick to push little vases to make them come crashing down. So I was amongst all the people who used to have lunch and dinner at The Ivy. There was always Larry and Vivien in one corner and Gielgud in another corner and Coward and his entourage would often be there and my mother and stepfather John Clements.”

Being a child, none paid him any attention – a deficit he rectified at Eton by misbehaving. “I was preposterously naughty. I was birched on the bare arse for tapdancing on a master’s desk and covering it in muddy boot marks.” Did it hurt? “Blood but no pain,” he recalls. “But a proper caning from a boy f***ing hurt like no tomorrow, let me tell you. They’d take a run and hit you as hard as they could.”

He was eventually “superannuated”, to use the Etonian term (“I call it sacked”) for failing exams. He went to Millfield in Somerset and disliked that too. Having made “a total Horlicks” of school, he pulled his finger out in the King’s Royal Rifle Corps, winning a commission. “I loved the kids in my platoon. All Londoners. Every other f***ing word, ‘John, you c***.’ Then I became an officer and suddenly I was ‘No, no, no, I’m not a c*** any more, I’m sir to you.’ We used to laugh so much.”

Back in civvies after two years in West Germany, in 1955 Standing went to art school where he was taught by R B Kitaj, two of whose works hang downstairs. He was intending to make a living with his brush until his mother told him to get a proper job and his DNA asserted itself. “I was terribly familiar with the smell of it. So I learned a bit of Shakespeare and went to Stratford. My audition must have been lamentably bad but I think they thought it was quite funny.” His first role was spear-carrying in Peter Brook’s touring production of Titus Andronicus starring Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh. On Olivier’s 50th birthday, Leigh asked him to join them for dinner in Paris with Colin Clark (whose role as Olivier’s gofer was memorialised by Eddie Redmayne in My Week with Marilyn).

Could he tell the state of the marriage? “Yes, not great, obviously. Larry didn’t utter a word he was in such a state about being 50. ‘It’s all over!’ It was a strange evening to say the least. Colin and I had to do most of the chat. Vivien was very well read, very well educated, much more than he was. But his magnificence on a stage…”

I had to be naked quite a lot of the time in front of a lot of Japanese schoolgirls who were very shocked with one’s poor old thing hanging out

Also in the cast was Anthony Quayle as Aaron the Moor. “I used to have to make him black. He said, ‘You’ve got to learn how to black me up. The dressers when we go to Poland and Yugoslavia won’t understand how to.’” He accepts that this is a vignette from another time. He’s less tolerant of other changes to the profession. “It is the most boring, dreary depressing thing, wokery, it really is.” He sighs forlornly. “It stops people being funny. You can’t be offensive. Great comedians were always offensive.”

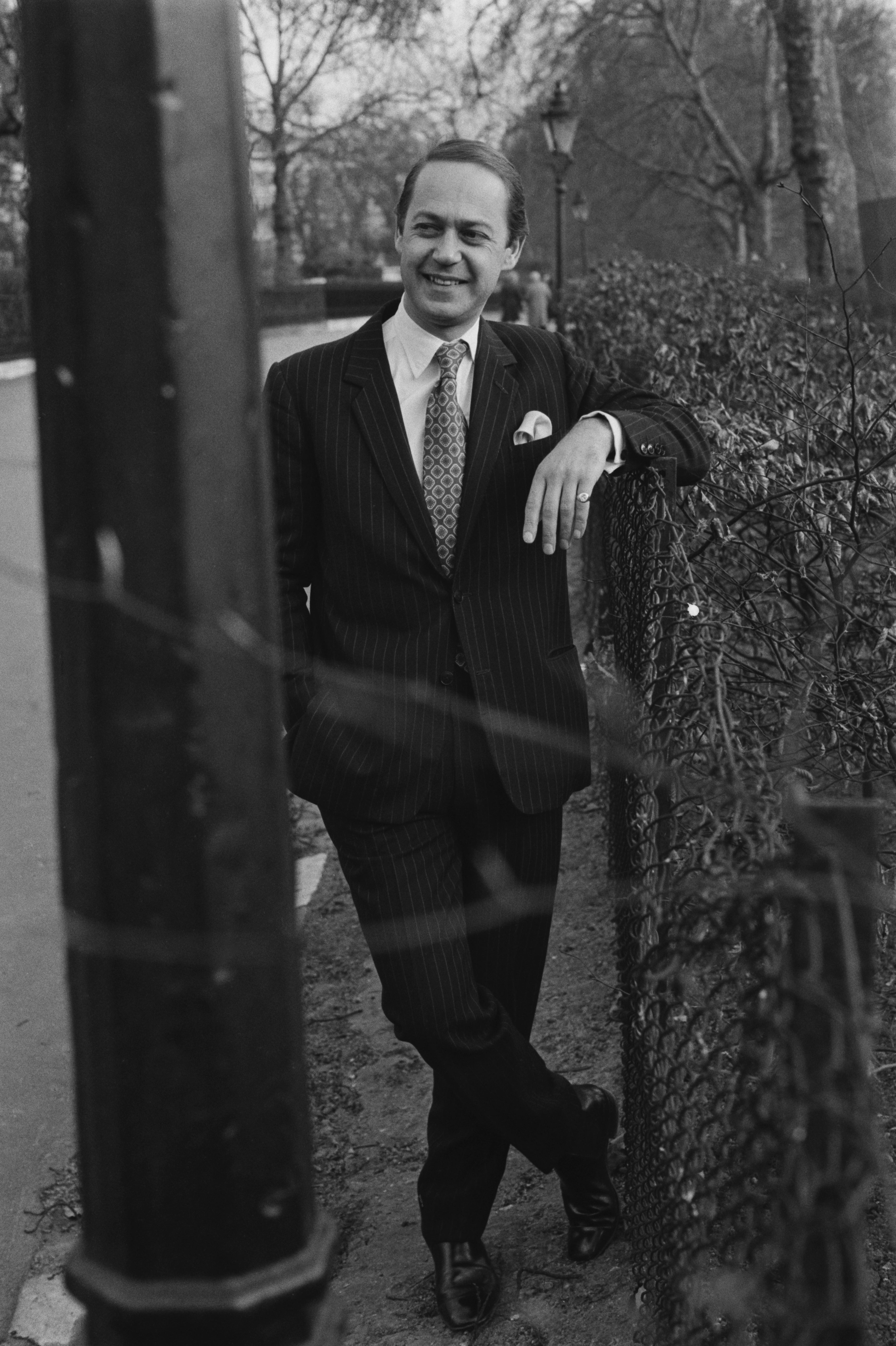

On the tight staircase up to his eyrie, there’s a beautiful poster advertising Titus Andronicus at La Fenice in Venice. Standing’s name props up the poster. Adjacent posters show it nearer the top as his theatre career flourished. Ring Round the Moon at the Haymarket with Flora Robson. The Importance of Being Earnest, when he and Daniel Massey corpsed so much one night in the muffin-eating scene that the stage manager dropped the curtain mid-performance. “It’s an appalling way to behave,” he accepts, “but it was electrifyingly funny.”

His biggest gig was Private Lives with Maggie Smith. He took over in 1972 at short notice after Smith and Robert Stephens, her husband and co-star, couldn’t stop rowing. Thus he was directed by John Gielgud. “He was adorable but he couldn’t make his mind up about anything! ‘My dear, stand over there. No, don’t stand over there.’ He used to ring me up from time to time. ‘I’m too terrified to speak to Maggie.’ He wanted me to speak to her on his behalf.”

He starred in Private Lives for 18 months in the West End, then on a US tour fetching up on Broadway. “Maggie and I did get on amazingly well. She is a master comedienne, stunningly clever. Then Jill Bennett took over who wasn’t funny, so it was uphill work. I played opposite all these girls. Judi Dench in Three Sisters. She’s naughty and likes to laugh. Vanessa [Redgrave] in a film of Mrs Dalloway, Eileen Atkins in A Delicate Balance. Eileen is a great friend.” The only time he acted with Glenda Jackson was at the script reading of The Great Escaper. “Which she did brilliantly. She died a really unhappy woman, I thought. I tend to like my fellow man. And she took life in a very angular way.”

He’s content that he never became comparably famous. “I don’t think I’m a romantic,” he says. “I’m just a balloon-faced clown figure. I’ve had a marvellous life. I’m the luckiest bastard ever, I think.” The rare screen leads that did come his way were random and various. In 1980, on the back of an Olivier Award nomination at the National, he was cast as Lorraine Chase’s MP boyfriend in the ITV sitcom The Other ’Arf. He discovered only after he’d signed to do four series that it was to be overseen rather than written by Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais. “The writing was lamentably bad.” Then, in 1999, he played a banker in Peter Greenaway’s 8 ½ Women. “I had to be naked quite a lot of the time in front of a lot of Japanese schoolgirls who were very shocked with one’s poor old thing hanging out. I’d been an art student. I wasn’t fussed at all.” (The extras may seem young in his memory, but they were clearly adults.)

Towards the end of our conversation, he slumps back, spent, as if the memories have been extracted at a cost. “Oh please,” he exclaims, “I can’t go on talking about myself!” Now and then we veer off into other passions – cricket, London architecture, his loathing of Brexit (but also grand actors pontificating about politics). I ask how he feels about old age. “F***ing hate it! And I’m going to die. The next gig is being wrapped up in one of those black plastic bags and hurled into the bin somewhere.”

He seems far from ready for it. Still up for working “if somebody offers me a job”, on the cusp of extreme old age he exudes a charming, indefinable boyishness. He has a wonderful smile. “I think I don’t look bad for 89,” he concedes. That ageless quality is captured in a performance of Hamlet’s “O what a rogue and peasant slave am I” soliloquy, which he worked up in 2020 while Sarah was having treatment for Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (from which she has fully recovered, and has written about in Dancing with the Red Devil, published earlier this year).

“I used to drive her to hospital and wait in the car and thought I can’t just wait like a great lemon, I must do something to keep this tiny thing I have up here active at some level.” He recorded it on the day bed in one unrehearsed take and posted it on Instagram this summer. It looks like the audition tape of a fine actor who is still Standing, not standing still.

The Great Escaper is out in UK cinemas now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

1Comments