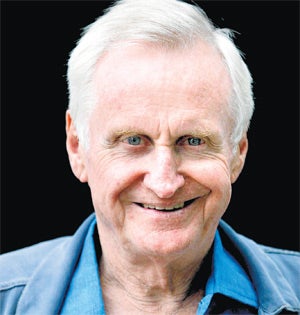

John Boorman - A very English visionary is back

No two films by John Boorman, the veteran British director of 'Deliverance', are quite alike. Up next, he tells Geoffrey Macnab, is a $25m animation of 'The Wizard of Oz'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.John Boorman has the fantasy bug. It is 40 years now since he tried, and failed, to adapt Lord of the Rings. United Artists had the film rights to JRR Tolkien's celebrated tale at the time, and had asked Boorman to make it into a movie.

"I spent many months on a script. It was going to be one film, not three," the English director recalls of his flirtation with hobbits and Middle Earth in the late 1960s – a period when he was still basking in the critical success of his thriller, Point Blank. Tolkien, with whom Boorman had corresponded during this period, was relieved that the film was to be made as live-action and not an animation. However, just as Boorman was ready to shoot, United Artists ran out of money.

"They couldn't afford it and so it was dropped," Boorman sighs. He tried to persuade Disney to step into the breach. "That didn't come off either. Disney were too worried about the violence." After several attempts at reviving the project, Boorman admitted defeat. "It was very fortunate because, had I made that film, we wouldn't have seen the wonderful trilogy that did get made [by Peter Jackson]. That was brilliantly done, much better than I would have done it." (Boorman doesn't comment on the animated version of Tolkien's yarn that was directed by Ralph Bakshi in 1978.)

The Lord of the Rings may have slipped through his grasp, but instead, the English director went on to make Deliverance (1972), Zardoz (1974), Excalibur (1981) and The Emerald Forest (1985) – all of which gave vent to his appetite for epic adventure. Now, Boorman , 76, is just about to start work on his first animated feature, aw, $25m version of another much loved fantasy, The Wizard of Oz.

"This is probably going to sound like a kind of heresy but I always found the film of The Wizard of Oz to be very clunky," Boorman confides of the celebrated MGM musical of 1939 in which Judy Garland danced down the yellow brick road in her red slippers. He insists that L Frank Baum's original novel is "much better than the film".Boorman's forthcoming foray into Munchkinland promises several significant twists on the Judy Garland version. "Why is Dorothy an orphan? How did she become one? And why is she so anxious to get back to this ghastly place, Kansas?" the director rhetorically asks. His screenplay will explore such questions in depth. It will also flesh out the backstories of Dorothy's friends the Scarecrow and the Cowardly Lion. Boorman is also planning to beef up the role of her loveable mutt, Toto, who will be given the power of speech.

As he waxes enthusiastic about the Tin Man and describes his plans for an epic new film about emperor Hadrian, you realise what an anomalous figure Boorman is in British film culture. While other directors of his generation (he was born in 1933) have made realist dramas or headed off to Hollywood to work for the studio system, Boorman has always plotted his own, idiosyncratic course. Look over his filmography and you will struggle to find any two movies that are overtly alike. It's a long way from the backwoods of Deliverance to the wartime London of Hope and Glory, or from the 1960s California of Point Blank to the muddy Camelot of Excalibur. Nonetheless, look beneath the surface, and common themes emerge.

Boorman might best be described as a very English kind of shaman, who regards cinema as a way of taking audiences into another world. During the mid-1980s, when he was making The Emerald Forest in a remote part of the Amazon rainforests, he was introduced to a local witchdoctor. Their conversation together was instructive.

"The tribes who lived [in the forests] had no notion that there was anything outside of their world," Boorman recalls. Through an interpreter, Boorman tried to explain what he did as a filmmaker. "'In a film', I said, 'you can move from one place to another. You can be very close to a person or you can be very far away. You can move very fast or slow.'" His listener, who had never seen a film or even watched television, seemed fascinated by this description of his craft. "The shaman said to me, 'this is exactly what I do in trance. I can go from one place to another. I can fly through the forest.'"

As a youngster, growing up in the London of the late 1940s and early 1950s, Boorman was fascinated by silent cinema, and, in particular, by the work of DW Griffith. "Griffith believed that film was the universal language promised in the bible," the director notes. "Cinema was a universal language when it started. It swept the world."

However, if cinema is a dreamlike art, it is also a business. It's a truism of film history that visionaries – or directors who chafe against the mainstream, even a little – are neither appreciated nor understood. Since Star Wars, Boorman suggests, the situation has grown even worse. The studios now target their films at 14-year-old boys, releasing them on thousands of prints and judging them as successes or failures on the basis of their opening weekend performance.

"Films used to open up in four or five major cities and then slowly roll out," Boorman recalls of the studios' old distribution campaigns, before George Lucas and Steven Spielberg burst on to the scene. He cites the example of Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, which was released on two prints and opened on one screen in New York and one in Los Angeles. Reviews were mixed and audiences were slow in coming. Kubrick couldn't find enough positive remarks from critics to put a "quote ad" together, so he contacted his filmmaker friends, Boorman among them, for upbeat comments. Gradually, the film became a success, but "In the present circumstances, it would have died ... it would have disappeared".

Boorman is a deceptive figure. At a retrospective of his work at the Midnight Sun Festival in Lapland recently, with his son Lee in tow, he cut a genial figure. He was happy to share anecdotes with his Finnish hosts about Lee Marvin's drinking, Marcello Mastroianni's womanising and Marlon Brando's unlikely admiration for Michael Winner. He explained the origins of the famous "squeal like a pig!" line in Deliverance. (The line was added late on in the editing process for the TV version, because the original dialogue was too full of expletives, but Boorman then decided to leave it in the theatrical release too.) And he didn't seem disgruntled when his films were shown on murky prints with very variable sound quality.

A polished and witty raconteur, he introduced screenings with gently barbed stories about the circumstances in which the films were made. At times, he seemed like a slightly less curmudgeonly version of the elderly eccentric played to such brilliant effect by Ian Bannen in Hope and Glory. However, well-mannered, cricket-loving Englishmen don't generally have the gumption to make epic movies in far-flung locations. Nor do they talk about cinema in the visionary terms that Boorman uses.

"As a member of an audience, I want a film to take me into another world, another universe, and to lose myself in it," he declares. "That is what audiences want: to be lost in a movie."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments