How two cousins made a documentary about their aunt, Joan Didion

The writer Didion gave unprecedented access to her archive for Griffin and Annabelle Dunne’s documentary and granted her nephew a series of honest interviews

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The actor and filmmaker Griffin Dunne learned that his aunt, the writer Joan Didion, had become the new face of the fashion brand Céline the same way the rest of the world did: he saw the picture on the internet. He was travelling at the time and, all of a sudden, he says, “my phone exploded. Everyone was calling about that photo”.

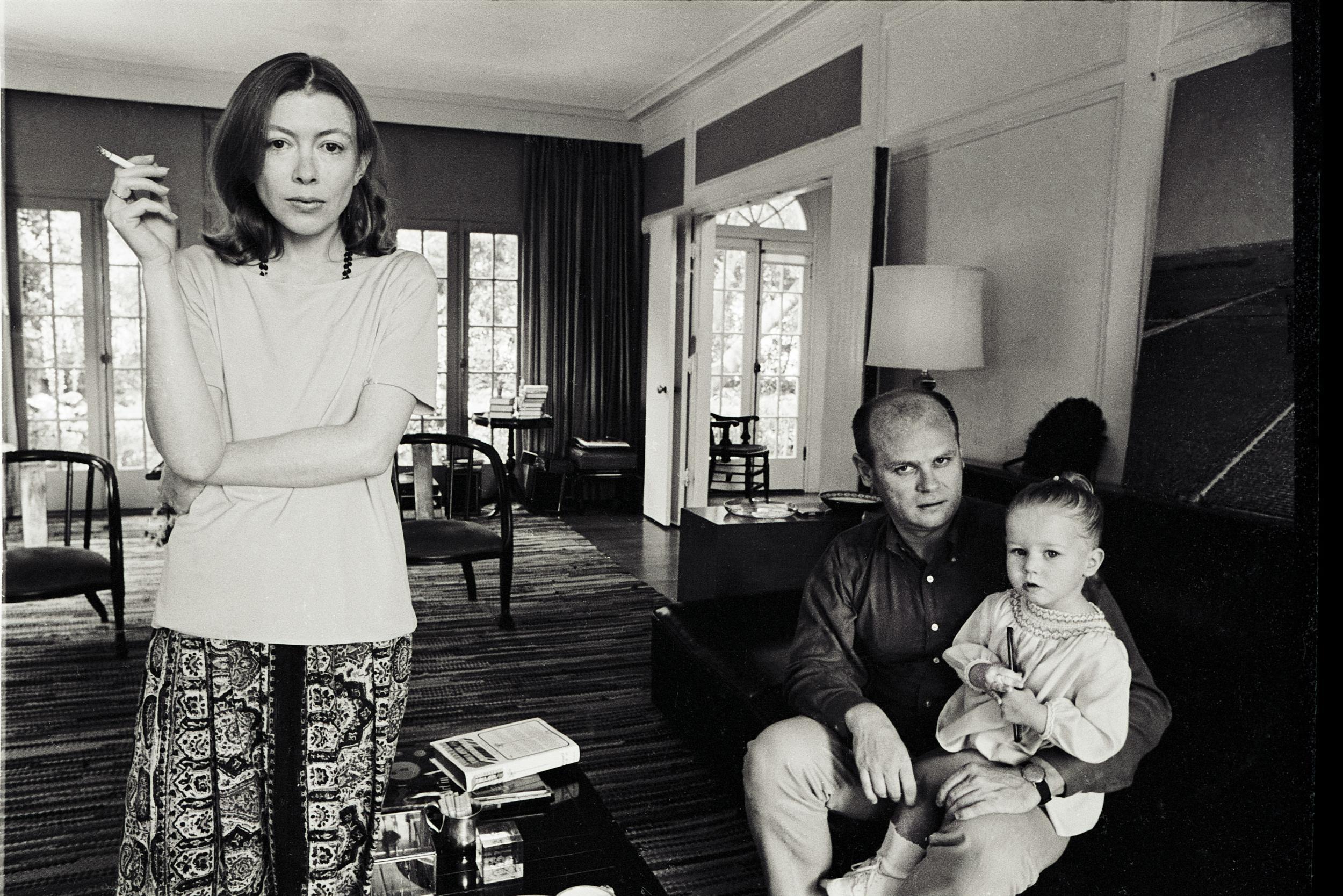

The 2015 photograph was certainly striking: Didion was perched on her sofa in a black turtleneck, her customary blunt silver bob and sunglasses so large they obscured half her face. Dunne had no warning about the advertisement, even though he had been working on a documentary about Didion’s life produced by his cousin (and Didion’s grandniece) Annabelle Dunne. Although they had been spending hours interviewing Didion, now 82, she kept the shoot a secret.

“But that’s Joan,” Annabelle says, sitting on a recent morning in her cosy West Village townhouse with a bespectacled Griffin, 62, drinking his second cup of coffee. “She’s still really savvy. She recognises good style, and how to create a moment.”

Didion was also savvy about whom she chose as her documentarians. She had been approached several times by filmmakers, but she turned them all down, Griffin says. It was only when she felt that the movie could stay within the family that she allowed unprecedented access to her archive and granted her nephew a series of frank interviews in a process that proved personally wrenching for him. As a member of a family that has been particularly touched by loss and grief, Griffin had to experience past tragedies all over again in order to make the film.

Though fans admire Didion’s ability to write coolly about matters of the heart, Griffin says he could not separate his emotions from the filmmaking. “It was always going to be a love letter,” he says. “She’s my Aunt Joan.”

In the new film, Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold, which is out on Netflix, Didion’s notably distant cool is immediately apparent when she discusses her classic 1967 essay, “Slouching Towards Bethlehem”, which chronicled the dark side of the hippie movement in San Francisco. While reporting on free love and flower children, Didion encountered a harrowing scene inside a flophouse, where a five-year-old girl was tripping on LSD. When Griffin pressed Didion to describe this incident for the documentary, she said: “Let me tell you, it was gold. That’s the long and the short of it, is you live for moments like that if you are doing a piece. Good or bad.”

Didion’s candid comment, recorded during a long conversation in 2013 that makes up the bulk of the documentary, reflects the levelheaded yet ambitious tone that made “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” and her first essay collection of the same name a national sensation in 1968. Though she had already published one novel, Run River, in 1963, it was her nonfiction that turned Didion into a writer-celebrity, a glamorous cultural space she still occupies five decades later. In her long career, Didion has published more than a dozen books, written or co-written six screenplays, and received the National Book Award and the National Humanities Medal.

Still, Griffin says, she waited a long time to consent to a documentary. “She kept saying no,” he says. “It wasn’t until she asked me to film the trailer for her book Blue Nights in 2011 that I started to think about being the one to do it. I saw how much she loved the process. I thought, this is all going so great, why don’t I just ask her?”

To his delight, she said yes. Writing via email, Didion says: “I’m still not sure it is the right time. Six years ago, when I said yes, it did not seem possible that the time to actually do it would ever arrive. I’m naturally sceptical that these things can work. But here we are.”

Annabelle says with a laugh: “Of course, neither of you knew what you were getting into,” and Griffin agrees.

“The gravity and the burden of responsibility only kicked in later,” he says, after it became clear how much interest there was in a Didion documentary. A crowdfunding campaign for the film reached its goal in one day and news that the project was in the works made international headlines. He realised he had “better not screw this up”, he says.

Griffin, who has directed five features including Practical Magic (1998), said that while Didion “is no chatterbox”, he felt that there was a cathartic effect to asking her about her past. Didion agreed, saying by email: “I felt at home with Griffin and Annabelle from the beginning. Feeling at home was most important. It was nice at the very least to talk to someone who knew John and Q. I couldn’t have described either of them to another interviewer.”

“John and Q” were Didion’s husband, the writer John Gregory Dunne, who died in 2003 after a heart attack, and her daughter, Quintana Roo Dunne Michael, who died as a result of an infection in 2005 at only 39. Griffin and his cousin have also experienced their share of grief — his sister Dominique was murdered in Los Angeles in 1982, and both of his parents, including his father, the longtime Vanity Fair writer Dominick Dunne, are gone.

“It was torture.” Griffin says of approaching the last quarter of the film, in which he raised the subject of loss with Didion, who had written two books exploring the tragedies, the best sellers The Year of Magical Thinking (2005) and Blue Nights.

“I think it was easier for her than it was for me,” he says, adding, “For me, the good news was I’m related, so I got permission to make this movie. The bad news was I am related, so I know all the people she lost. Quintana is my cousin, John is my uncle, and I have to make her go through it all over again. If I was a more dispassionate, regular documentarian, that would be questions on the clipboard.”

Still, Didion, who saw several cuts of the film along the way, says: “I did find it fortifying to know that I was telling these secrets to people who regarded them as such.”

The feeling was mutual. “I was really conscious of how just through attrition, there was just Joan and I in the room,” Griffin says. “It’s probably one of the reasons she let me make the movie. I know all those people who are not here, I loved all those people, we share that love.”

“Without being too mystical, I was always aware of my parents, and John, and Quintana, in the editing room,” he adds, his chin shaking, fighting back tears. “And I think they would have liked it.”

‘Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold’ is out on Netflix

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments