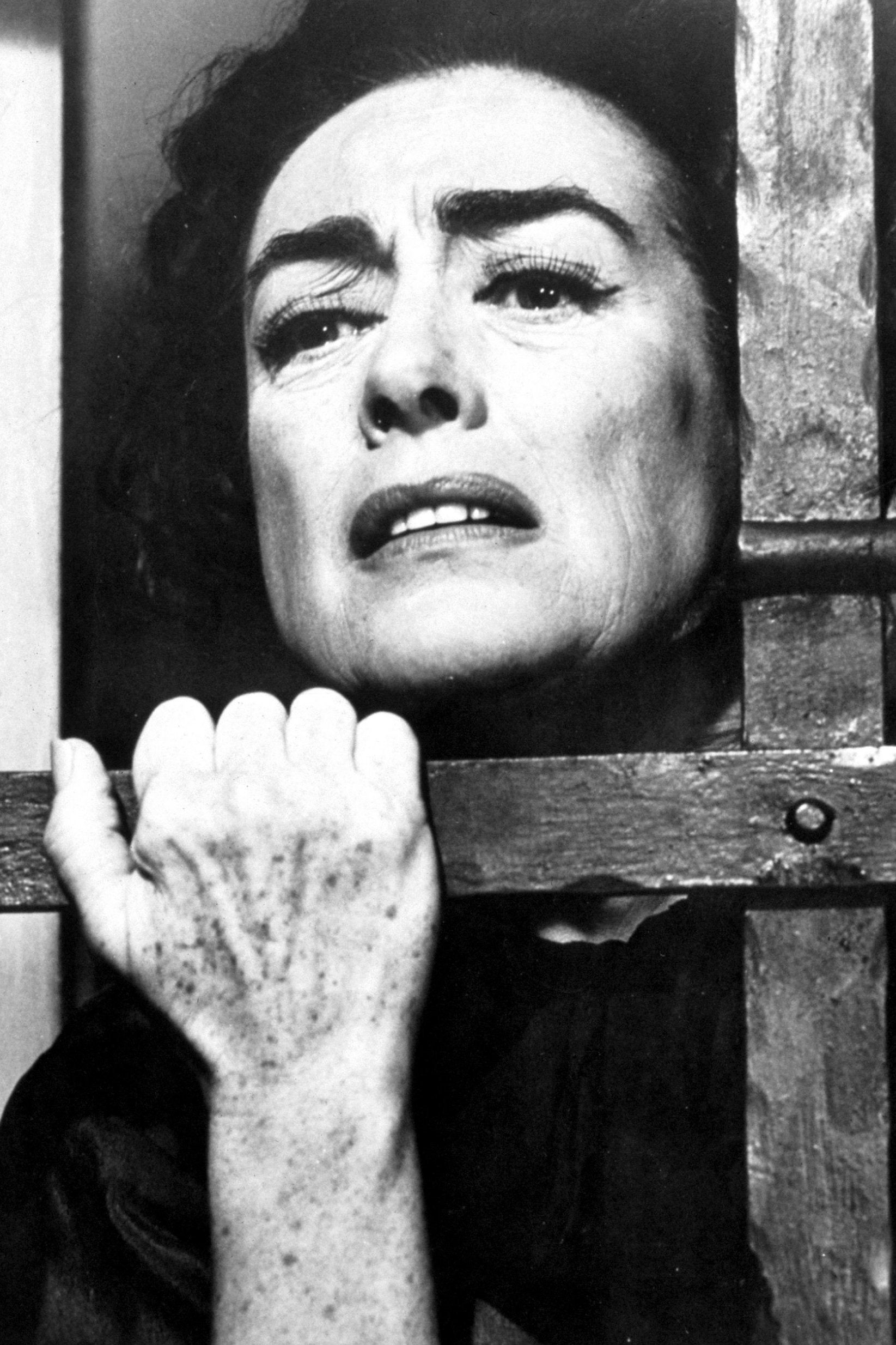

Joan Crawford: A Master of Reinvention

The subject of a film season at the British Film Institute in London, Crawford was a magnetic yet shrewdly calculating actor

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Joan Crawford understood the power of reinvention. From the wide-eyed, carefree flapper of the silent era, to the prowling, coolly natured screen goddess of The Women (1939), to the camp icon of What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962), Crawford moulded and remoulded herself, refusing to be cast aside when she grew out of starlet roles.

Recently, she’s been on our screens again: first as portrayed by Jessica Lange in the US drama Feud, now as part of the BFI’s two-month season Fierce: The Untameable Joan Crawford. So why is she still so beguiling, after all these years?

Born Lucille LeSueur in San Antonio, Texas, she had a difficult childhood. Not only did her parents divorce, but she was sexually abused by her stepfather. It was at his theatre that she became fascinated by vaudevillle; indeed, it’s not hard to imagine they offered her some means of escape, if only for a brief moment.

She first launched her career as a chorus dancer, performing in travelling revues, before making her way to Broadway to appear in the chorus line of 1924’s Innocent Eyes. The prospect hardly satisfied her, however, and she pushed for more work, eventually securing a screen test and her first Hollywood job, as Norma Shearer’s body double in 1925’s Lady of the Night.

A handful of small, uncredited roles later, and she was finally pinned for her big break by MGM’s head of publicity, Pete Smith. And thus, her first step towards transformation began: Smith was convinced her name sounded phony, so he threw the reins to the general public, organising a contest titled “Name the Star” in Movie Weekly magazine.

Joan Crawford was eventually settled upon. Blossoming in her new identity, Crawford threw herself in every direction across Hollywood in the hope of securing bigger and better quality parts, gathering trophies from hotel dance competitions to centre herself as Hollywood’s new it girl flapper.

Her calculations paid off and, following roles in Sally, Irene and Mary (1925) and Our Dancing Daughters (1928), she became an equal to the formidable Clara Bow, though it was Crawford that F Scott Fitzgerald described as “the best example of a flapper, the girl you see in smart night clubs, gowned to the apex of sophistication, toying iced glasses with a remote, faintly bitter expression, dancing deliciously, laughing a great deal, with wide, hurt eyes. Young things with a talent for living.”

Crawford thrived during the transition from silent film to talkies, eagerly accepting the larger cultural shifts. The Roaring Twenties came to their conclusion and the Great Depression opened its cavernous jaws; Crawford, in turn, shifted towards less girlish, more sophisticated roles, starring across from Clark Gable in Dance, Fools, Dance (1931), Laughing Sinners (1931), and Possessed (1931). She constantly lobbied for better, more dramatically inclined parts, never shying away from altering her own image in pursuit of those goals.

After endless hours of elocution practice, her southwestern drawl was replaced by the favoured mid-Atlantic accent. She altered her mannerisms, even changed her laugh. “It grew softer, more modulated, less spontaneous. It became a finishing-school laugh,” her first husband, Douglas Fairbanks Jr, once recalled. She refused to leave the house until she looked like Joan Crawford, the movie star.

That dedication allowed her career to flourish during the 1930s, but it was a success not without its expiration date. On 3 May 1938, Harry Brandt, the president of the Independent Theatre Owners Association of America, published an open letter in the Independent Film Journal, listing several stars he deemed “Box Office Poison”, whose inflated salaries saw no justification in ticket sales they brought in. Crawford was among those named, alongside the likes of Greta Garbo, Katharine Hepburn, and Fred Astaire. Sadly, Brandt’s declaration ran true: Crawford suffered a string of flops.

Her survival instinct kicked in and Crawford moved into what’s now become her most memorable period of work: the age of complex women. In 1939, she fought to play second-string to a star she’d long deemed her own nemesis, Norma Shearer, in George Cukor’s The Women.

The move bemused Hollywood, but hindsight has allowed us to see just how shrewd Crawford’s calculations were; as Crystal Allen, the unapologetic, calculating seductress who has Mary (Shearer)’s husband wrapped around her finger, Crawford is nothing short of magnetic.

The Women initiated a pattern of unconventional roles. For Strange Cargo (1940), she shed her usual high glamour to trek across jungles with Clark Gable; for A Woman’s Face (1941), she wore prosthetics to play a blackmailer marked by burn scars. Best known, however, is her role in Mildred Pierce (1945), as a woman who gives everything to provide for her daughter, but is spited in return.

Director Michael Curtiz fought against Crawford playing the part, but it was the star who had the last laugh: she won the Academy Award, and doors started swinging back open for her.

Thanks to a contract with Warner Bros that guaranteed her approval on all scripts, she continued to seek layered, conflicted women to play and remained popular throughout the 1950s. This marked Crawford in full ownership of her career.

Humoresque (1947) centred on the love affair between an older woman and a young man; Possessed (1947) saw her play an emotionally unstable woman obsessed with her ex-lover, earning an Academy Award nomination in the process. She was also nominated for Sudden Fear (1952), in which she played a woman whose husband is plotting to kill her. However, by the early 1960s, Crawford’s career once more fell into decline.

Crawford, dutifully, looked to another transformation. Here, it infamously came in the form of What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? Crawford hoped that the electricity sparking off her public feud with Bette Davis would resuscitate her career.

This was aided, surely, by the film’s brazenly melodramatic plot, adapted from Henry Farrell’s 1960 novel of the same name. In it, Bette Davis plays Jane Hudson, a quadriplegic former actress held captive in her own home by her delusional sister Blanche, played by Crawford. For once, the gamble failed to pay off. Davis stole the limelight and nabbed the Oscar nomination.

Instead, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? offered only momentary success, giving way to professional decline, as Crawford was relegated to repeating her new horror shtick in William Castle’s Straight-Jacket (1964) and I Saw What You Did (1965). She made her last appearance on film in the sci-fi shlock Trog (1970), before her death in 1977.

She left behind a career that spanned 45 years and more than 80 films – a feat only possible due to her endless ingenuity, and her ability to shift guises to reinstate herself as Hollywood royalty. As a well known quote, uttered by MGM screenwriter Frederica Sagor Maas, goes: “No one decided to make Joan Crawford a star. Joan Crawford became a star because Joan Crawford decided to become a star.”

‘Fierce: The Untameable Joan Crawford runs’ at the BFI until 4 October. ‘Mildred Pierce’ and ‘The Women’ are now screening in select UK cinemas