Howards End's James Ivory: 'I don't have some morbid preoccupation with detail for the sake of detail'

It's time to see beyond the frocks of Merchant Ivory films with the rerelease of 'Howards End', which has undergone a digital 4K restoration overseen by the director

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Merchant-Ivory’s Howards End (1992) is being given a major rerelease in British cinemas this month, 25 years on from its original release.

As it hits our screens again it is easy to forget just how polarising and contentious Merchant Ivory’s work once seemed. These films, produced by Ismail Merchant and directed by James Ivory, were a mainstay of British cinema at a time when the UK industry was in a parlous state during the mid to late 1980s and early 1990s.

However, to their critics, features like their EM Forster adaptations Room With A View, Maurice and Howards End were abominations. They stood for “heritage cinema”, a cosy, nostalgic and middlebrow escapism that gilded the past while ignoring contemporary social and political reality. They were famously dismissed by Alan Parker as being from the “Laura Ashley school of filmmaking”, while academics attacked them as “visually spectacular pastiche” that presented a picture postcard view of Edwardian Britain likely to appeal to American tourists.

The films’ lavishly detailed costume and production design was held against them. They were seen as snobbish and pretentious. This was the Thatcher era and here were Merchant Ivory turning out prettified period pieces based on old novels. England was burning and they were making “frock flicks.” In the mid 1980s, with the miners on strike and British cinema attendance at an all time low, Merchant Ivory was shooting A Room With A View, with its upper-class characters splashing around naked or going on trips to Florence.

A quarter of a century later, most of these criticisms seem wildly misplaced. We realise now that the best Merchant Ivory films were just as astute in their treatment of the class system, injustice and exploitation as most of the social realist dramas with which they were compared so unfavourably. Nor did the detractors seem to notice the nuance and skill with which the team’s regular screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala (a Booker Prize-winning novelist in her own right) adapted the books they made movies from.

Ivory, now 89, oversaw the restoration of Howards End together with the cinematographer, Tony Pierce-Roberts. No, this wasn’t a case of a film that had been neglected or vanished. It won three Oscars, including one for Emma Thompson as Best Actress, and has never really fallen out of circulation.

“The film was in fine shape,” the director told me at the Cannes premier of the restored version last year. “The negative was at the George Eastman House in Rochester [one of the world’s oldest film archives] along with all our other negatives. No bad thing had happened to it.” However, he says the digital 4K restoration has now improved the colour and sound of the film in time for its reappearance in British cinemas.

The director’s producer partner, Ismael Merchant, had made the arrangements with George Eastman House to collect the Merchant Ivory negatives. Three or four years before his death in 2005, Merchant set to work pulling together the material from the 40 or so films he and Ivory had made together, starting with The Householder in 1963.

Howards End is the first of several restorations that US company Cohen Media, which bought the Merchant Ivory Library in late 2015, is currently planning. It ranks with their very finest work. Adapted from EM Forster’s 1910 novel, it’s an Edwardian family drama with just as fraught and embroiled a plot as that of any TV soap opera. It has adultery, pregnancy, feuds over money and property, misunderstandings, acts of brutality and extreme snobbery alongside examples of decency and selflessness.

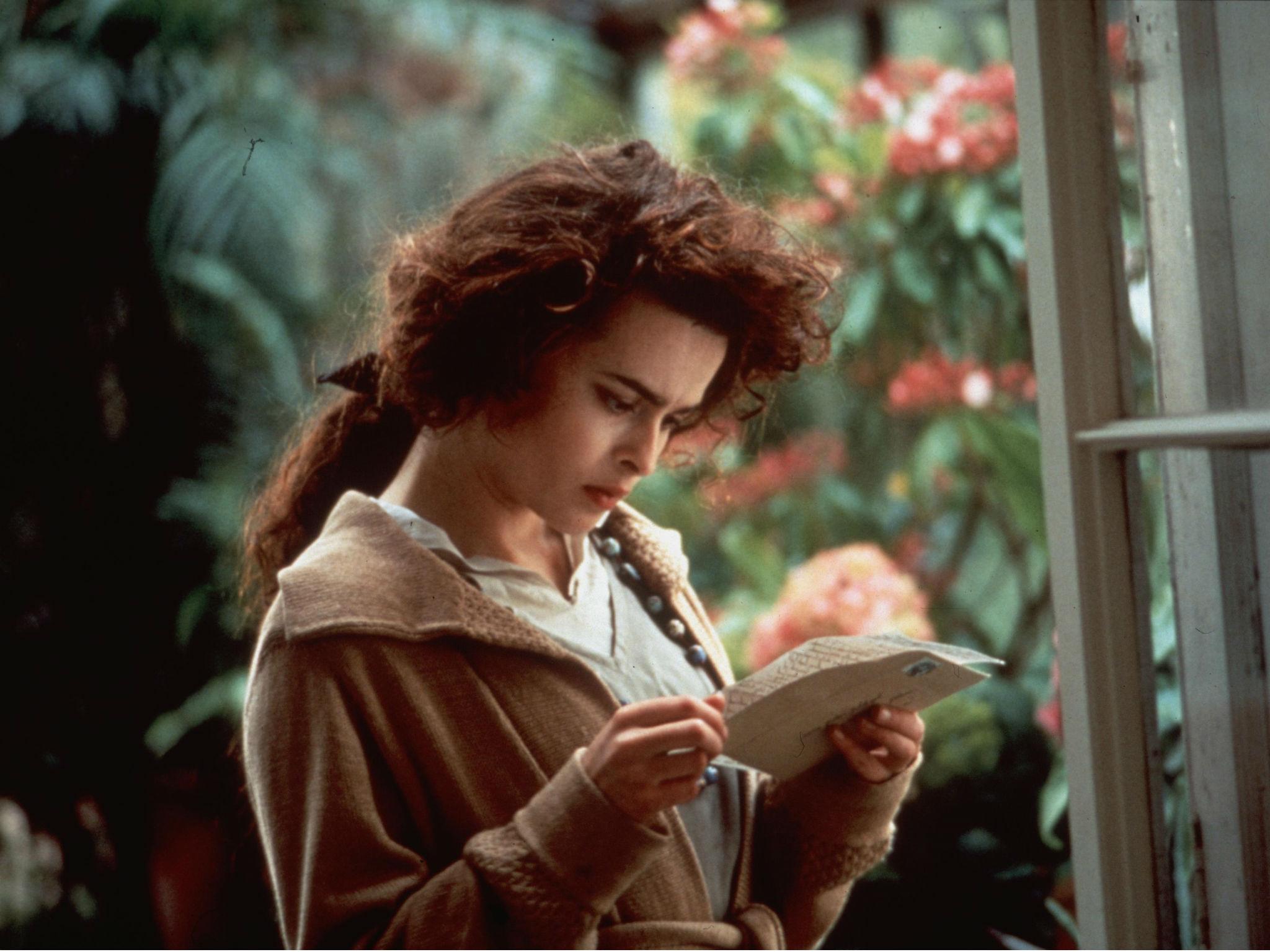

It also boasts some exceptional performances. Emma Thompson excels as the idealistic but strangely naive Margaret Schlegel. Helena Bonham Carter is almost equally good as her bluestocking sister. Anthony Hopkins brings a quiet intensity to his role as the ruthless but deeply repressed businessman, Wilcox, while Vanessa Redgrave impresses as the ailing but lambent Mrs Wilcox, who strikes up an unlikely friendship with Margaret. There’s also a poignant and creepy performance from Sam West as Leonard Bast, a frustrated young clerk with intellectual leanings who wants to better himself in a society that shuns him.

A quarter of a century on, films like Howard’s End and Remains Of The Day have a double fascination. They’re period pieces that also cast light on the era in which they were made. They are also notable for the talent they foregrounded. They gave early opportunities to newcomers such as Hugh Grant (in Maurice and Remains Of The Day), Helena Bonham Carter and Daniel Day-Lewis, who all went on to become major stars. They provided the platform for established actors like Anthony Hopkins to give some of the finest performances of their careers (in Howards End and Remains Of The Day).

Merchant Ivory is the name of the production company that the director and producer set up, but it has also been used in a very loose fashion as a label to describe their style of filmmaking. Their detractors can often make it seem that their entire career was based around making movies about the lives of overdressed aristocratic types in Edwardian times. Look through their filmography, though, and you’ll find work set in India, the US and France as well as in the UK. There are biopics, contemporary dramas and comedies alongside the costume dramas. Ivory is American and Merchant was born in India.

Ivory recently co-wrote and produced Call Me By Your Name, the latest feature from Luca Guadagnino (the Italian director of director of I Am Love and A Bigger Love Story.) Starring Armie Hammer, this gay love story is being talked up as a potential Oscar contender. He also announced plans to adapt Shakespeare’s Richard II for the screen with Tom Hiddleston in the lead role.

You can plot a line from the exhaustively detailed Merchant Ivory “heritage films” of the 1980s and 1990s to much of the equally lavish period drama being made today (from Parade’s End to Downton Abbey) in what is considered a golden age of TV drama.

Ivory disliked the idea Merchant Ivory always paid too much attention to costume and production design, to the trimmings rather than to the meat of their stories. “I’ll be damned if I am going to listen to people who criticise me for taking great pains to do things in the proper way,” he told me in 1999. “That’s what I call production value. It is not, absolutely not, some morbid preoccupation with detail for the sake of detail.”

He likened the unseen work that goes into a Merchant Ivory film to the “bottom of an iceberg” and argued that, without their meticulous approach, their films would have only a fraction of their power.

Maybe now, a quarter of a century on, audiences and critics will be able to approach these films without being distracted by the debates about heritage cinema and Laura Ashley. It is time to see beyond the frocks.

‘Howards End’ is rereleased on 28 July

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments