From Buddies to Blue – the pioneering Aids films that paved the way for It’s A Sin

Russell T Davies’s new Channel 4 drama has its characters fighting until the very end – DNA it shares with two groundbreaking films of the Aids crisis, writes Katie Driscoll

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A naked light bulb in a dark and ruined room” is how British filmmaker and gay activist Derek Jarman described his mind while his body was decaying from the effects of Aids. It’s a Sin, Russell T Davies’s latest series on Channel 4, keeps that light alive, celebrating the legacy of the people at the frontline of the Aids pandemic – the people who fought and died for the advancements we have today.

In the five-part drama, set between 1981 and 1991, HIV/Aids doesn’t reverberate openly – it is spelled out in hushed conversations, guesses and conspiracy theories, homophobia an implicit and contagious part of modern life. What stands out most, though, is how fully alive its central characters are. The Seventies and Eighties brought with them a new liberation for the LGBTQ+ community, and Colin, Ritchie, Ash and Roscoe take full advantage of that, as they dance and laugh their way through parties and trysts. They are sparkling, gorgeous, funny and alive, in stark contrast to the later dread of the hospital room, where they are left to stew in shame without human contact. Still, Davies’s series has its characters fighting until the very end – DNA it shares with two pioneer films of the Aids crisis.

Before Tom Hanks played an Aids victim taking on a prejudiced legal system in 1993’s Oscar-winning Philadelphia, there was Buddies. Released in September 1985, a full four years after men began dying from Aids, underground gay filmmaker Arthur J Bressan Jr’s film was nonetheless the first to depict the crisis onscreen. Rarer still, it was made by and about gay men during a time when the US and the UK still prohibited schools from “promoting” homosexuality.

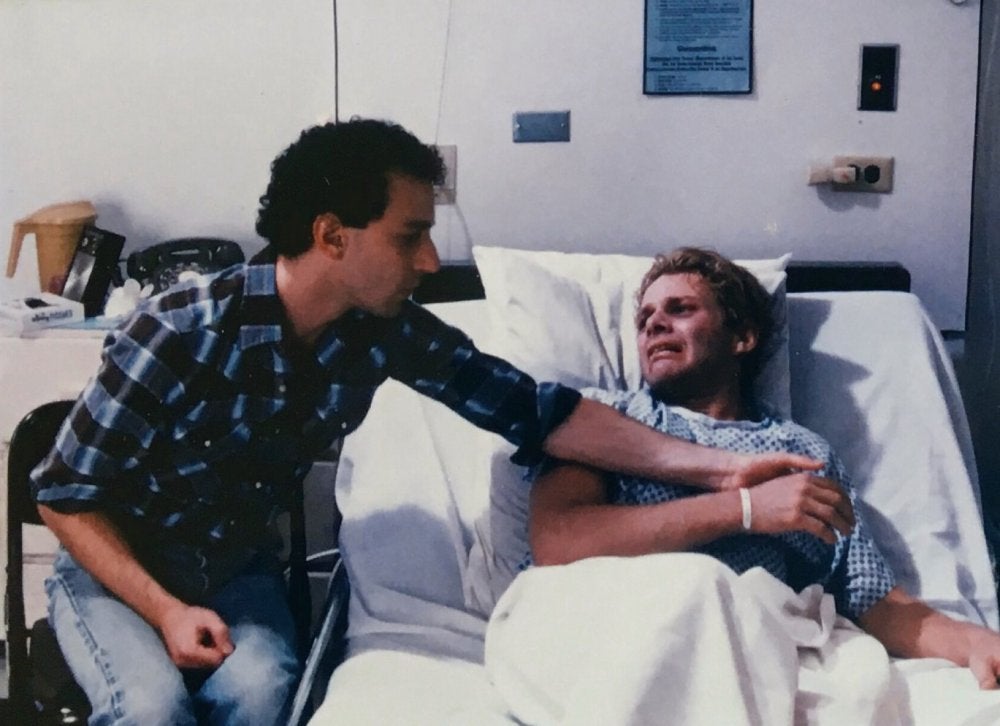

The film is an exercise in empathy through cramped and isolated hospital rooms, challenging the assumptions of gay men like David (David Schacter). David takes on the role as volunteer “buddy” to Aids sufferer Robert (Geoff Edholm), whose only contact with the outside world has been through doom-laden newspaper headlines. Before Aids became a subgenre of the tearjerker movie, Buddies favoured simplicity and honest dialogue over raw emotion. The film is scattered with real-time footage of protests and marches, showing history in the making – the Reagan-era-ravaged city piling up the dead.

Hollywood’s role in commercialising Aids onscreen is problematic when Aids patients are more of a plot point than a fully fleshed human being – when empathy is formed and then quickly forgotten once the credits roll. It stings that no one wanted to depict or be associated with Aids until it was safely relegated to the past, by which time they could milk audience tears and Oscars from it. Dallas Buyers Club gave its transgender character Rayon (Jared Leto) Aids but no semblance of identity outside of her disease and gender.

Derek Jarman’s final film Blue – an experimental meditation on melancholy, affinity and the disease that was slowly destroying him – was released at the tail end of the Aids pandemic (1993), when there were 2.5 million cases worldwide. A single static shot of blue screen serves as a symbol of decay: Jarman was losing his sight due to Aids complications, only seeing the world through a blue hue. He muses on the colour blue, like the “roaring water” where he hears the “voices of dead friends”, chanting names of dead lovers like an incantation.

With eviscerating images, Jarman situates us totally in his subjectivity. We have no choice but to bear witness to his lived experiences. It’s a brave piece of work that immerses the viewer in his mind, looking out from his eyes, the surreality of being a part of a world of neon signs in bustling London, the same world where there is always “infection bubbling at the corner”. Eight years after Buddies wasreleased, Blue painted the world in much of the same way – although there had been advancements in medicine, there was still no way out of Aids except in a coffin.

Like Buddies, Blue allow us the privilege of experiencing Aids through first-hand accounts of its victims; Derek Jarman became a figurehead of the Aids movement in Britain by virtue of being one of the few who were public about their status, and Arthur J Bressan Jr passed away from the illness a mere two years after completing his film. Both films were radical in creating a space where Aids could be more universally considered – Blue was released on primetime TV and on BBC radio – and paved the way for a world where It’s a Sin was broadcast to 6.5 million views during its first week on Channel 4.

Given that there were only 428 Aids-related deaths in the UK in 2017 (out of 101,600 people living with HIV) compared with over 500,000 in 1990, it’s easy to think of the Aids crisis as a thing of the past. But the stigma still sticks: many people who watched It’s a Sin felt a heady mix of guilt and shame – for not being aware enough, or perhaps not caring enough, about what was happening on their streets and beyond their doorsteps.

These films don’t exist as relics but guide maps for art that continues to represent and explore the lives of Aids victims, activists and survivors. It’s a Sin has arrived in the cultural consciousness at a time when a pandemic of a different nature has become our shared collective reality; there is less stigma attached to coronavirus, but the show still serves as a reminder to keep in check our shared humanity instead of blaming a marginalised group.

Buddies ends with David, who has grown close to Robert, unable to look away from the crisis: “that room and all his dreams and hopes and memories”. It speaks to the unfairness of time cut short, illuminating the burden of a shared past that Hollywood schmaltz like Philadelphia and Dallas Buyers Club dismissed, choosing instead to drown reality in theatrics.

While he’s lying in his childhood bed, dying of Aids, It’s a Sin’s Ritchie tells his mum he doesn’t want to be a secret. “Boys die in London, and they say it’s cancer or pneumonia, and they don’t say what it really is,” he tells her, his voice weak. “But it’s a lie, and I don’t want that. You know why?” He breaks into a smile. “I had so much fun.” It is a sentiment shared by Jarman in Blue, and by Robert in Buddies. Even when the world was telling them otherwise, they refused to regret how they’d lived their lives – clinging to the beauty of life beneath the degradation of death.

It’s a Sin is available now on All 4

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments