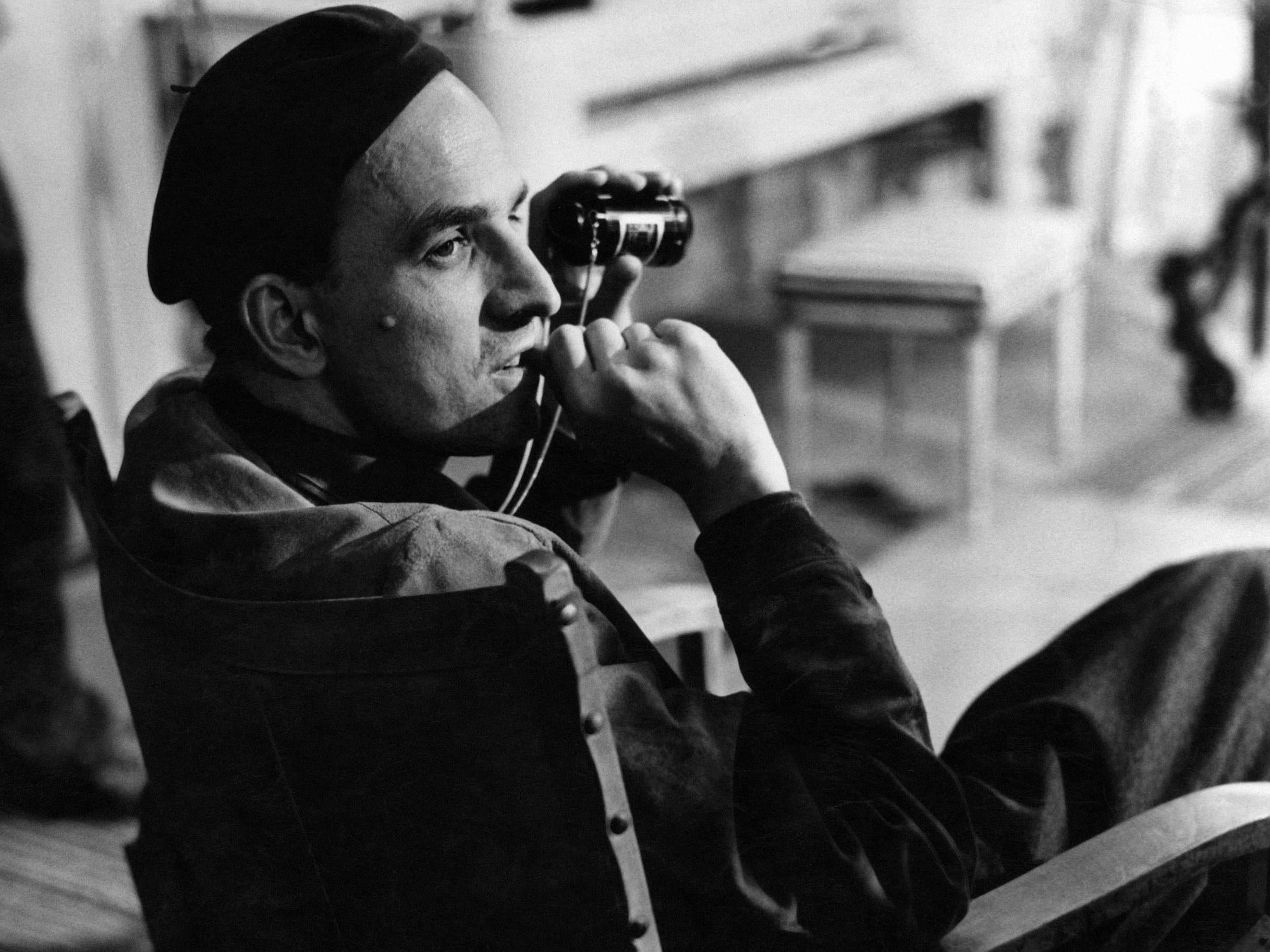

Ingmar Bergman: The messy life of a magic filmmaker

As a new documentary about Ingmar Bergman is released, Martin Chilton reflects on the method behind the legendarily intense Scandinavian filmmaker’s madness

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There are many sides to Ingmar Bergman, the filmmaker who came up with that unforgettable image of a medieval knight on a seashore playing a game of chess with Death.

As an 83-year-old, Bergman stood up after watching George Clooney and Julia Roberts in Ocean’s Eleven to enthusiastically tell his family they must watch the film again. This is less incongruous when you acknowledge that for eight decades the so-called “gloomy Swede” was a self-confessed movie addict who had been captivated by the cinema since seeing his first film at the age of six.

In a career as one of cinema’s true visionaries, he made more than 55 films, including masterpieces such as The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries, Through a Glass Darkly, Winter Light, The Silence, Cries and Whispers, Persona, Scenes from a Marriage and Fanny and Alexander. As a person, though, he was destructive and disorderly, a temperamental boss and a predatory womaniser. His story is explored in a new documentary film called Bergman: A Year in a Life, which is directed by Jane Magnusson, a Swedish filmmaker.

For many years it was an accepted narrative that Bergman suffered lifelong mental scars from a desolate and physically abusive childhood in Uppsala. He called his mother Karin “cold and rejecting” and said his father Erik, a volatile Evangelical Lutheran parson, was a violent parent who beat Ingmar, elder brother Dag and younger sister Margareta, frequently locking them up in dark closets.

“One of the strongest feelings I remember from my childhood is of being humiliated; of being knocked about by words, acts or situations,” Bergman told Torsten Manns, the co-author of Bergman on Bergman. He repeatedly described himself as “a scared child” and, at the age of 53, was still complaining to television interviewer Dick Cavett that his “pedant” father had been “very tough, very hard” on him. After fleeing home, he told Cavett, he did not speak to either of his parents for five years.

We don’t know how much he manipulated the story of his childhood, but we should be wary of trusting a man who said he was always enthralled by “cruel fairy-tales” and who described himself as “a talented liar”. It seems that Ernst Ingmar Bergman, who was born on 14 July 1918, constructed his own mythology. The makers of Bergman: A Year in a Life looked at more than 400 hours of interviews and behind-the-scenes footage and the result is a fresh perspective on the punitive taskmaster father, who was later to become chaplain to the Swedish royal family.

For one thing, it is not clear which child bore the brunt of the parson’s anger. “It is hard to tell when Bergman is being untruthful about his childhood and when he’s embellishing and just being a great storyteller,” Magnusson tells me. “One thing I did find during the production was that his older brother’s versions of key events in their childhood differs quite a bit. It seems Bergman borrowed stories about his brother and ascribed them to himself. At the same time, Bergman’s brother was a notorious sadist. He tormented his younger brother when they were children; maybe he continued this process until late in life. You never really know with the Bergmans.”

What is clear is that being forced to attend hundreds of bleak church services in remote Swedish villages, especially during an era of staunch moral rectitude, instilled in the young Ingmar a lifelong distrust of religion and its practices. In an interview in Bergman on Bergman, the filmmaker admits he was repelled by “the poverty of their sermons, and the nonchalance and indifference of the ritual”. He believed that clerics in Sweden were propagating a system “to create obedient slaves, with God at the top”.

The solution to this controlling religious upbringing was for a highly imaginative boy, a natural day-dreamer, to devise his own world, one in which the creations did what he wanted. After starting with magic lantern projection displays, he moved on to complicated puppet theatre shows, producing his own Strindberg spectacles – Bergman quickly got used to pulling all the strings.

A key person in his life was his maternal grandmother Anna Calwagen. This humourous woman, whom he later described as his “best friend”, regularly accompanied him to the cinema, a passion ignited by the thrill of seeing his first film, a silent version of Black Beauty from 1921, which was so preferable to home life and the school he “hated”.

At Stockholm University, where Bergman studied art and literature, he spent most of his time around the student theatre. Almost the only other thing he seems to have been ardent about in his teenage years was the charismatic power of Adolf Hitler, whom he saw address a Nazi rally in Weimar during a summer holiday.

After he left university, his film career began in earnest in 1941 with some work re-writing scripts. Over the next decade, he patiently learned his craft by directing or writing. The first time he took on both roles was for the 1949 film Prison (released as The Devil’s Wanton in America), which he later dismissed as “a mess”.

The 1950s was his breakthrough decade, with highlights such as Summer with Monika (1953) and the 1955 Palme d’Or nominated Smiles of a Summer Night (a favourite of his acolyte Woody Allen). The transformative year in his life was 1957, which is at the core of Magnusson’s documentary. Magnusson calls 1957 “Bergman’s mad year”, because in addition to releasing The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries, he also directed his first television film and put on four stage shows, including a demanding production of Henrik Ibsen’s Peer Gynt.

Bergman was exploring his feelings about death and religion (and Christian architypes) in The Seventh Seal, themes that helped spawn the adjective “Bergmanian”. Disillusioned knight Antonius Block (Max von Sydow) returns from the Crusades to find that the plague is wiping out his homeland. It is a memorably dark movie. “Love is the blackest of all plagues,” bemoans one character. “Isn’t life a dirty mess?” asks another. The film includes the startling image of the knight playing Death – in the form of the Grim Reaper – at chess. Death, who naturally uses the black pieces, wins. In the disturbing finale, the cloaked figure leads a chain of doomed victims across a desolate moor.

Bergman, who was 39 at the time and already suffering from stomach ulcers that frequently woke him in pain in the early hours, said that his fear of death “was overwhelming” when he made the film. He called his phobia “an infantile fixation”, although possibly it was an inevitable consequence of a childhood spent watching hundreds of funerals. “I felt myself in contact with death day and night, and my fear was tremendous,” Bergman said. Only half in jest, he once said that the reason he had no real interest in politics was because “the only party I ever belonged to was the Party of the Scared”.

The Seventh Seal “was good medicine” for Bergman, and helped him overcome his pre-occupation with death. By the time he was in his late fifties, he was sanguine about the inevitability of the grave (or good at pretending this was the case). “I used to be scared of death, but now I think it a very, very wise arrangement. It’s like a light that is extinguished. Not very much to make a fuss about,” he told Charles Thomas Samuel.

Wild Strawberries, released in December 1957, is also full of haunting, indelible images – such as a clock with no hands and shocked look on an old man as he is being pulled into the coffin by his own dead body. Some reviewers saw a message of salvation in the film, suggesting that the main character, the 78-year-old widowed Professor Isak Borg (superbly played by Victor Sjöström), is redeemed through compassion after a lifetime of emotional detachment.

When Bergman was asked in 1964 whether the film was a positive tale of redemption, Bergman was unconvinced. “But he doesn’t change. He can’t. That’s just it,” he told Playboy magazine. “I don’t believe that people can change, not really, not fundamentally. Do you? They may have a moment of illumination, they may see themselves, have awareness of what they are, but that is the most they can hope for.”

Bergman may have been reflecting on his own inability to change because 1957 was a year of wild affairs, during which he met Käbi Laretei and Ingrid von Rosen, who would go on to become his fourth and fifth wives. During the making of The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries, he was also enjoying an intense affair with 22-year-old Bibi Andersson, the lead actor in both films. At the time, his marriage to the journalist and linguist Gun Grut was starting to unravel.

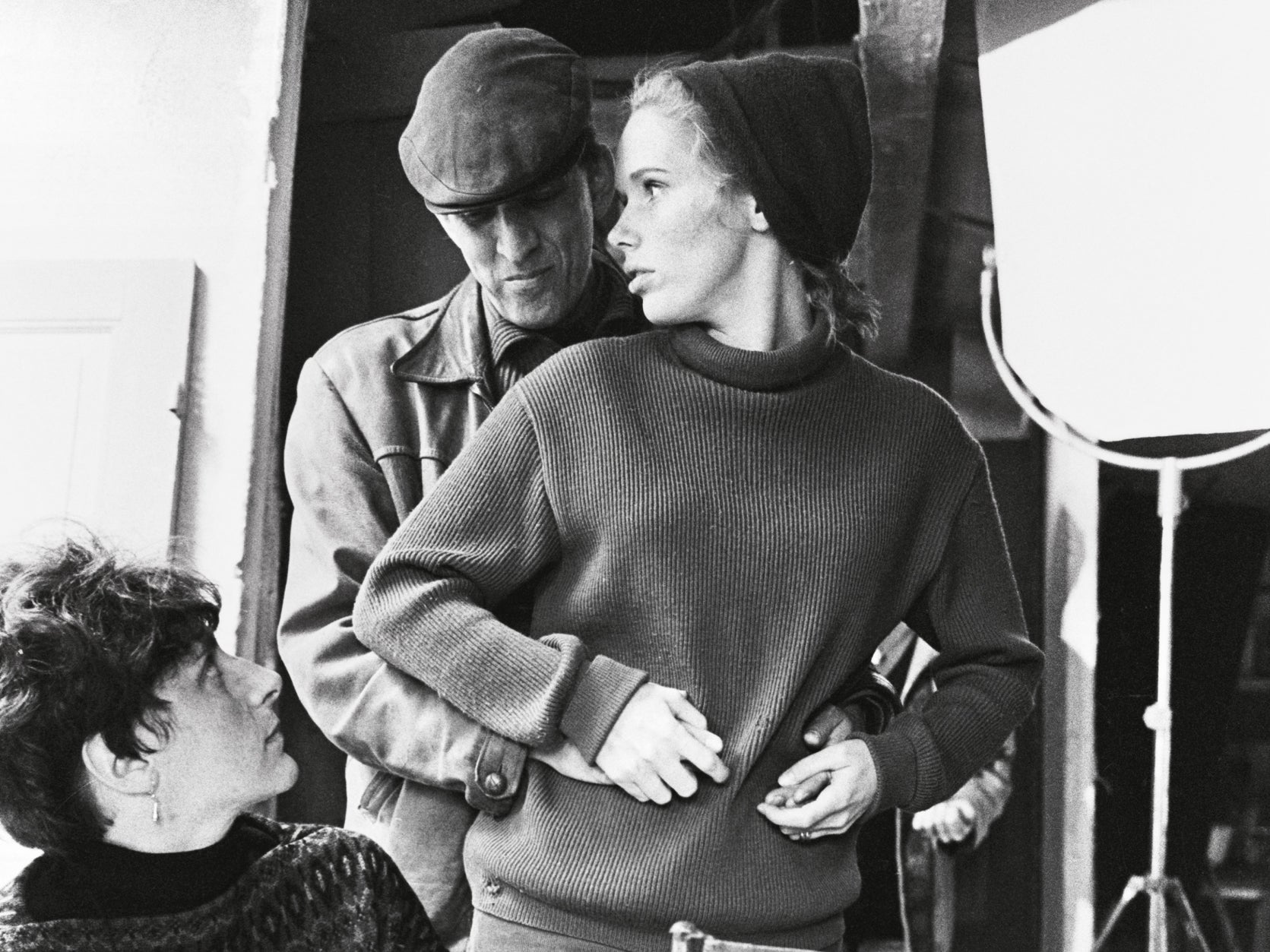

His personal relationships with women seem at odds with his respect for them on screen. “Some people who watch my films say, ‘what a horrible sexist, how could you make a film about someone so unfaithful and abusive to women?’” Magnusson says. “This certainly is a valid point when you consider Bergman’s private life. And it is truly strange that he, at the same time, gave his actors such amazing roles. In films like Persona, The Silence, Cries and Whispers and Autumn Sonata we have two female leads, sometimes more. In this aspect Bergman is ahead of his time, even today. He was born in 1918 – maybe his attitude to women in his personal life reflects his generation.”

For 1971’s The Touch, Elliott Gould became the first American to star in one of his films and the actor remembers a rather salacious man, who told him he had once “jerked off” after seeing a Mae West film. Bergman told Gould he wanted to build “a f***ing machine” – a platform with a hole cut in it for the camera to peek through – to film the sex scenes between Gould and Bibi Andersson. “I had a feeling that Ingmar wanted Bibi and me to share our intimacy off-camera, and that was not to be,” Gould later told The New Yorker magazine.

When he died on 30 July 2007, aged 89, Bergman left behind eight children (his son Jan, who had appeared in his 1968 film Shame, had died of leukaemia at 54), whom he had largely ignored during their formative years. He had dozens of mistresses and would justify the affairs to his various wives by telling them: “I have so many lives.” He said one of the reasons he became such a workaholic – in addition to his films and plays, he wrote radio dramas, a novel and even a libretto – was to escape “the fiasco” of his personal life. “I wanted to become a good director because as a human being I was a failure. In the studio and the theatre, I could live happily. I still feel that way,” he told The New York Times.

He surrounded himself with devoted actors – including regulars such as Harriet Andersson, Gunnar Bjornstrand, Bibi Andersson, Max von Sydow and Liv Ullmann – and utilised the same set of superb technicians. David Lean once asked Bergman about his modus operandi. “I make my films with 18 good friends,” Bergman told the acclaimed director of Doctor Zhivago. “That’s interesting,” Lean replied, “I make mine with 150 enemies.”

Bergman’s core crew was his alternative family and the members of that clan seemed to love and respect the sometimes despotic paterfamilias. “Ingmar was an extraordinary theatre director, an inspirer and teacher for his actors. He created a relationship between all the people he worked with. He was a very sensitive, intelligent man who knew a lot about human beings,” Von Sydow said.

As ever with Bergman, this is not the whole story. He was not universally respected. The Oscar-nominated Lena Olin (best known for her role as femme fatale Sabina in The Unbearable Lightness of Being) experienced the nasty side of Bergman during rehearsals for a production of Strindberg’s A Dream Play. Olin said Bergman was “very furious” when she told him she was pregnant. “He was very unforgiving. He was really mean,” she recalled.

Actor and filmmaker Mai Zetterling (who worked with Bergman in the 1940s) said he only really liked actors who were “one of his puppets”, while Ingrid Bergman (who appeared in Autumn Sonata in 1978, just four years before her death from cancer) was so upset by Bergman’s demanding approach on set that she slapped him.

It seems he was also something of a chip off the parson’s block when it came to 11-year-old Bertil Guve. Bergman had chosen Guve to play a character based on the young Bergman in the autobiographical Fanny and Alexander. During one scene, Guve laughed unexpectedly, causing Bergman to lose control. “He jumped up and grabbed my arm and said: ‘This is the most outrageous, the most unprofessional behaviour I have ever seen,’” recalled Guve. The child was left in tears by Bergman’s manhandling.

Bergman admitted he could be “cruel” to actors and conceded he had a short fuse. There are examples in Magnusson’s documentary of his rages on set. He is also shown as control freak who could fly into a tantrum if a crew member ate one of his favourite biscuits. “Bergman always had a terrible temper, from his early days as a theatre director – to his last productions,” says Magnusson. “People want to work with him despite his tantrums, mainly because working with Bergman could lead to amazing roles outside Sweden. Not that I really understand this motivation – what’s wrong with working in Sweden? As Bergman got older his temper got worse. The crap that people had to put up with at the Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm during the 1990s is insane. He crushed and destroyed people and should have been told to go home. But he kept the crowds coming and no one intervened.”

Bergman was sufficiently self-aware – and arguably crafty enough – to admit his flaws to interviewers. “I am very much aware of my own double self. The well-known one is very under control; everything is planned and very secure. The unknown one can be very unpleasant. I think this side is responsible for all the creative work — he is in touch with the child,” Bergman told The New York Times Magazine in 1983.

On set, everything was meticulously planned. Gould praised Bergman’s impeccable organisational skills as a director, saying that “every day on set was administered to perfection”. In preparation for making Winter Light in 1963, Bergman and cinematographer Sven Nykvist would sit for hours every day in a church in northern Sweden, just so they could see how the light changed between 11 and two o’clock each day. Nykvist, who won an Oscar for 1972’s Cries and Whispers, was one of his most regular collaborators over three decades and said he learnt so much about the importance of location and natural light from Bergman. “Initially, I was quite apprehensive when I first met Ingmar, because he was known as the ‘demonic director’. But from the first day, we worked well together. Perhaps we understood each other because we were both the sons of pastors,” Nykvist said in an interview for the book Cinematography Screencraft by Peter Ettedgui.

Bergman was also a prolific theatre director and, from 1963 to 1966, he was head of the Royal Dramatic Theatre, Stockholm. Nykvist believed this experience was another key element to his success as a filmmaker. “Because Ingmar had worked in the theatre, he was fascinated by light and how it can be applied to creating a mood. One of the unique privileges of working with Ingmar was that there were a few actors who were always in his films. I came to know their faces intimately, and learnt how to photograph every detail. It takes time to learn how a face will take light.”

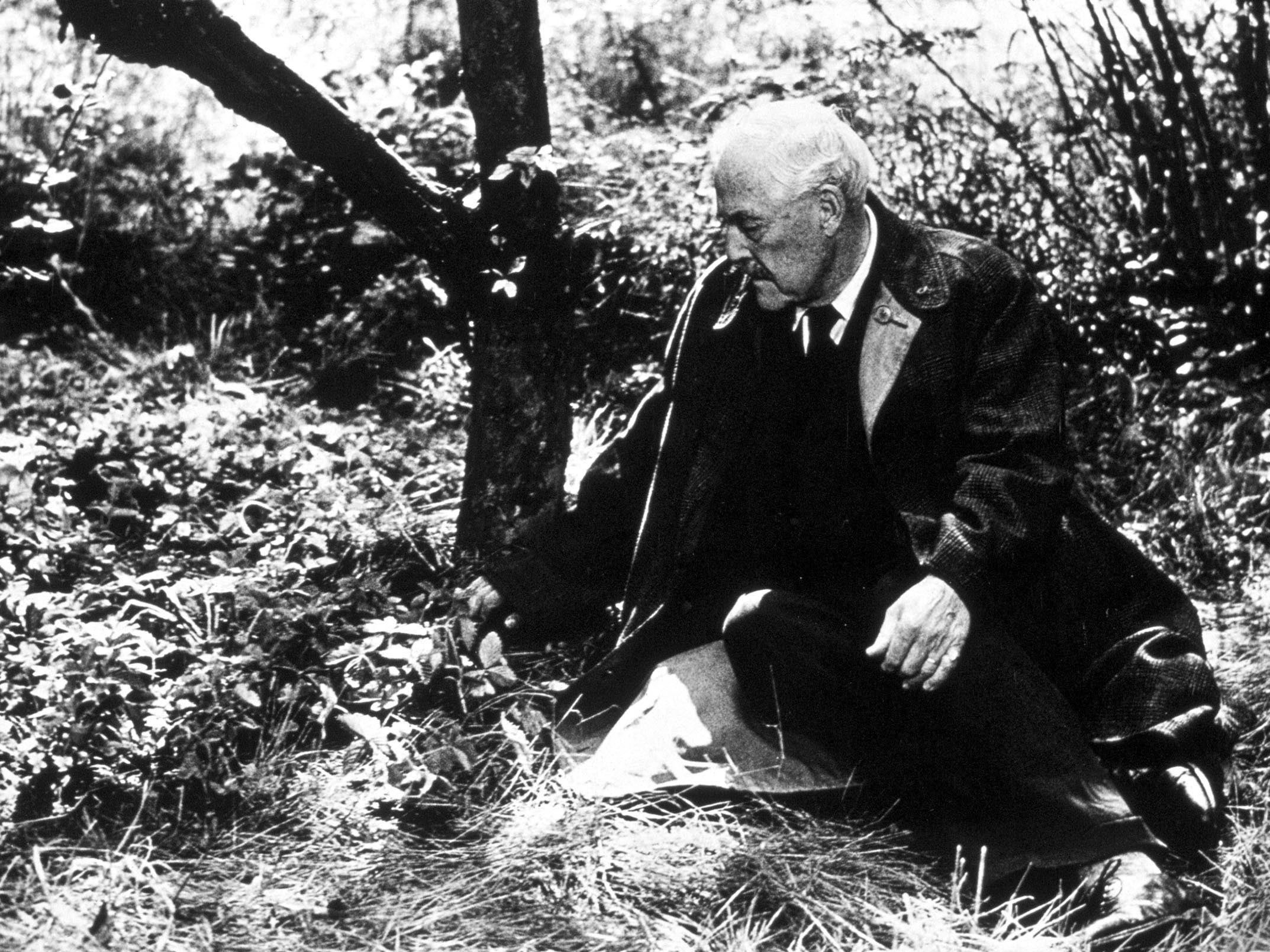

This obsession with the look on an actor’s face is central to Bergman’s brilliance. “Faces are a big thing. The human face is the most cinematographic thing that exists. It is sensational and fascinating to look at a face,” Bergman told Melvyn Bragg. Reflecting on his legacy, Bergman said that the emotion he captured in a lingering shot of Sjöström towards the end of Wild Strawberries revealed everything about the tenderness and the sadness of life slipping away. “That’s one of the most beautiful close-ups I got in my life,” Bergman said.

Although Bergman’s films were revered throughout the world, his home country’s attitude towards the filmmaker was something hostile. In 1976, during a theatre rehearsal in Stockholm, he was arrested for alleged tax evasion and interrogated for hours while his house was searched. Although the charges were dropped and the Swedish government issued a formal apology three years later, the experience helped trigger a nervous breakdown and Bergman went into exile in West Germany. It took him years to forgive his treatment by the Swedish authorities.

When he returned to Uppsala in 1981, it was to begin filming Fanny and Alexander, a movie that would be hailed as a modern classic. Fanny and Alexander followed The Virgin Spring (1960) and Through a Glass Darkly (1961) in winning the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. Bergman, indifferent to gala ceremonies, unplugged his phone in his Munich flat and slept through the announcement of his final Academy Award win. In all, Fanny and Alexander won four Oscars, yet after all the acclaim, he announced that he would not direct a film again. “I want peace. I don’t have the strength any more, neither psychologically nor physically. And I hate the hoopla and the malice. Hell and damnation,” Bergman told Reuters.

Although he continued to work occasionally – his final film, a drama for television in 2003 called Saraband, was well received – his final years were spent quietly on Fårö, the remote Baltic island where Bergman lived on and off from the early 1960s until his death. It was a bleak setting. Incoming phone calls were strictly rationed to an hour each week. Liv Ullmann, who had been Bergman’s partner between 1965 and 1970 and remained close after they split, said that he used to mark black crosses on a door for periods of depression. She called Fårö “that miserable dark island”.

It wasn’t all joylessness, though. Bergman remained a voracious film watcher on his island home, although not of his own films, which he said made him feel jittery and tearful. Henning Mankell, author of the Wallander novels, was married to Bergman’s daughter Eva and he recalled that Bergman hosted screenings every day at 3pm, in the state-of-the-art cinema he had built in a converted farmhouse. Bergman used to sit in the front row, with his own special foot stool, and Mankell especially remembers the director’s enthusiasm for the remake of Ocean’s Eleven. “Jesus!” said Bergman, as the credits rolled. “We need to see this again next week.”

Ullmann believed that the public didn’t get to see her former lover’s lighter side. “He is, to a certain degree, optimistic in life, but he doesn’t put it into his movies,” she said. When a Swedish film magazine asked for negative reviews of The Seventh Seal, Bergman used a pseudonym and penned an attack on himself. He had a dry wit. After joking with Dick Cavett about the time he consulted a psychiatrist about his “restless legs” in bed, he noted drolly that the shrink had been very polite and said: “Yes, Mr Bergman I have seen all your pictures and I have been waiting for you!”

Bibi Andersson said that when she first worked with him as a 16-year-old schoolgirl, after he hired her for a series of one-minute cinema adverts he was making for Bris soap bars, she was struck by his love of practical jokes, adding, “Ingmar is very funny when he shows you movements you should do in scenes.”

Andersson also made the salient point that Bergman “was so full of neuroses that if he took them away he would not be able to make films anymore”. Maybe that is an essential clue to the mystery of Bergman. He was ruthless and his private life was messy, yet he knew how to exploit his own demons. “I have learnt that if I can master the negative forces and harness them to my chariot, then they can work to my advantage... Lilies often grow out of carcasses’ arseholes,” was his vivid explanation in 2001 to Reuters.

Stanley Kubrick is among those who consider him “the greatest filmmaker” of the 20th century. So how do we square our admiration for the movies with the flawed man who made them? “All the good and bad things I have learnt about Bergman during production, have not made me like him less,” says Magnusson. “In fact, he becomes more fascinating because he is so open about his shortcomings. He isn’t the first negligent father, unfaithful husband, or megalomaniacal artist – he is just more honest about it. Truth be told, I don’t think him being all these things makes, say Persona, less of a masterpiece.”

In that candid interview with Playboy, Bergman talked about the magic of cinema and summed up his quest for the meaning of love, truth and mortality. “What matters most of all in life is being able to make that contact with another human. Otherwise you are dead, like so many people today are dead,” Bergman said. “But if you can take that first step toward communication, toward understanding, toward love, then no matter how difficult the future may be – and have no illusions, even with all the love in the world, living can be hellishly difficult – then you are saved. This is all that really matters, isn’t it?”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments