Indiana Jones and the tempor of doom: The trouble with time-travel in the movies

As ‘Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny’ is released next week with a jarring time travel plot, Geoffrey Macnab looks at why certain movies thrive on skipping through the centuries or reeling back the years, while others fail dismally

In the new Indiana Jones film, The Dial of Destiny, out next week, Harrison Ford’s rugged archaeologist is up to his usual daredevil tricks. He and his even more thrill-seeking goddaughter Helena (Phoebe Waller-Bridge) compete against a former Nazi scientist turned Nasa adviser (Mads Mikkelsen) to get hold of the Antikythera, a contraption from ancient times that has been split in two. Anyone who can put it back together will be able to leap across the aeons and potentially reverse history.

In other words, the film provides just the rip-roaring fare we all expect and love whenever Indiana Jones has a new adventure.

For much of the movie, we think that the Antikythera is just another “MacGuffin”, as filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock used to call devices put into movies to keep the plot ticking along, but that turn out to have no particular significance. It’s a rusty-looking metal box that has been around since the time of Archimedes.

However, in a minor spoiler alert, the dial does indeed facilitate time travel. In an ill-conceived final reel set piece, the main characters in the movie leave the 20th century and arrive in another era altogether.

After the grudging and equivocal reviews the film was given following its Cannes Film Festival premiere last month – “short on both thrills and fun”, concluded The Hollywood Reporter and “an ultimately rather joyless piece of nostalgic hokum”, said Variety – it’s likely that its screenwriters would like to go back in time themselves and rewrite their ludicrous plotlines.

The first 20 minutes of the film, in which we see Ford’s Indiana Jones in flashback as a young man tussling with German soldiers, are terrific. Watching the last 20 minutes, though, you’re quickly reminded that time travel in certain movies is a very bad idea, especially when filmmakers are shuffling their characters thousands of years forwards or backwards in time, like pawns being moved randomly across a gigantic cosmic board.

IMDB lists well over 800 time travel films, but there are very few you’d want to watch again. Clockstoppers? Freejack? Time Flies? The Mark Twain novel A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (1889) about a mechanic in 1912 who bumps his head and finds himself in Arthurian Britain in AD528 has been the subject of several clunky movie adaptations – the 1949 film starred Bing Crosby.

There’s a good reason why we don’t see many films about time travel like this today. It’s jarring when characters from different centuries are hurled together into the same melting pot – and this is exactly what happens at the end of The Dial of Destiny. It isn’t a spoof and it isn’t a sci-fi picture. That’s why the sudden burst of time travel is so intrusive and incongruous.

No one is pretending that the first Indiana Jones adventure, Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) was an exercise in Ken Loach-like documentary realism. Inspired by serials like Zorro and Spy Smasher that its director Steven Spielberg used to watch as a kid, it is a matinee adventures with all the trimmings, a “Disneyland ride” as Spielberg called it.

The blockbuster sequels and prequels (The Temple of Doom, The Last Crusade, The Crystal Skull etc) are equally far-fetched. They have chases, swarming insects, explosions and lots of wry humour. Nonetheless, they still possess a dramatic coherence that the new film lacks.

Certain movies thrive on skipping through the centuries or reeling back the years. It happens often enough in Marvel and DC superhero yarns. Nobody complains either when in, say, a cheesy comedy like Hot Tub Time Machine (2010) some disillusioned and depressed middle-aged male friends are suddenly transported to the rowdy, carefree 1980s after having a dip in a Jacuzzi. The film is supposed to be crude and vulgar. “If you are a connoisseur of sexual, scatological or just plain stupid humour, you will find your appetite satisfied, even glutted,” The New York Times wrote in a generally approving review of a picture that aimed low and hit its target right in the nuts.

Nor are there many grumbles about films in which the undead leap across time. You expect Christopher Lee’s louche, cape-wearing Dracula to turn up in swinging London in 1972 and it doesn’t seem too strange when the “immortal” played by Christopher Lambert in Highlander (1986) exchanges 16th-century Scottish glens for the mean streets of contemporary New York.

When directors go highbrow and embrace the physics behind time travel, they can get away with plotlines that simply wouldn’t be tolerated in more conventional movies. Few critics complained about Christopher Nolan’s brilliant, very cerebral sci-fi thriller Interstellar (2014) in which “time dilation” means that weeks spent by characters in deep space are experienced as years by their loved ones back on Earth. The net result is that their children age far more rapidly than they do – this worrisome aspect of time travel isn’t addressed in the new Indiana Jones film.

George Pal’s 1960 version of HG Wells’s post-apocalyptic sci-fi tale The Time Machine won an Oscar for special effects that still seem pretty nifty today. The film begins in vivid fashion with George Wells (Rod Taylor) returning to Victorian London after five days away. He’s just in time for a dinner party with his sceptical scientist friends. He suddenly bursts through the door into the dining room looking exhausted and bedraggled. They pour him a stiff drink and then he tells his outlandish story about his recent journey far into the future. Unlike in The Dial of Destiny, the time travel isn’t just tagged on at the end. It’s the entire justification for the film.

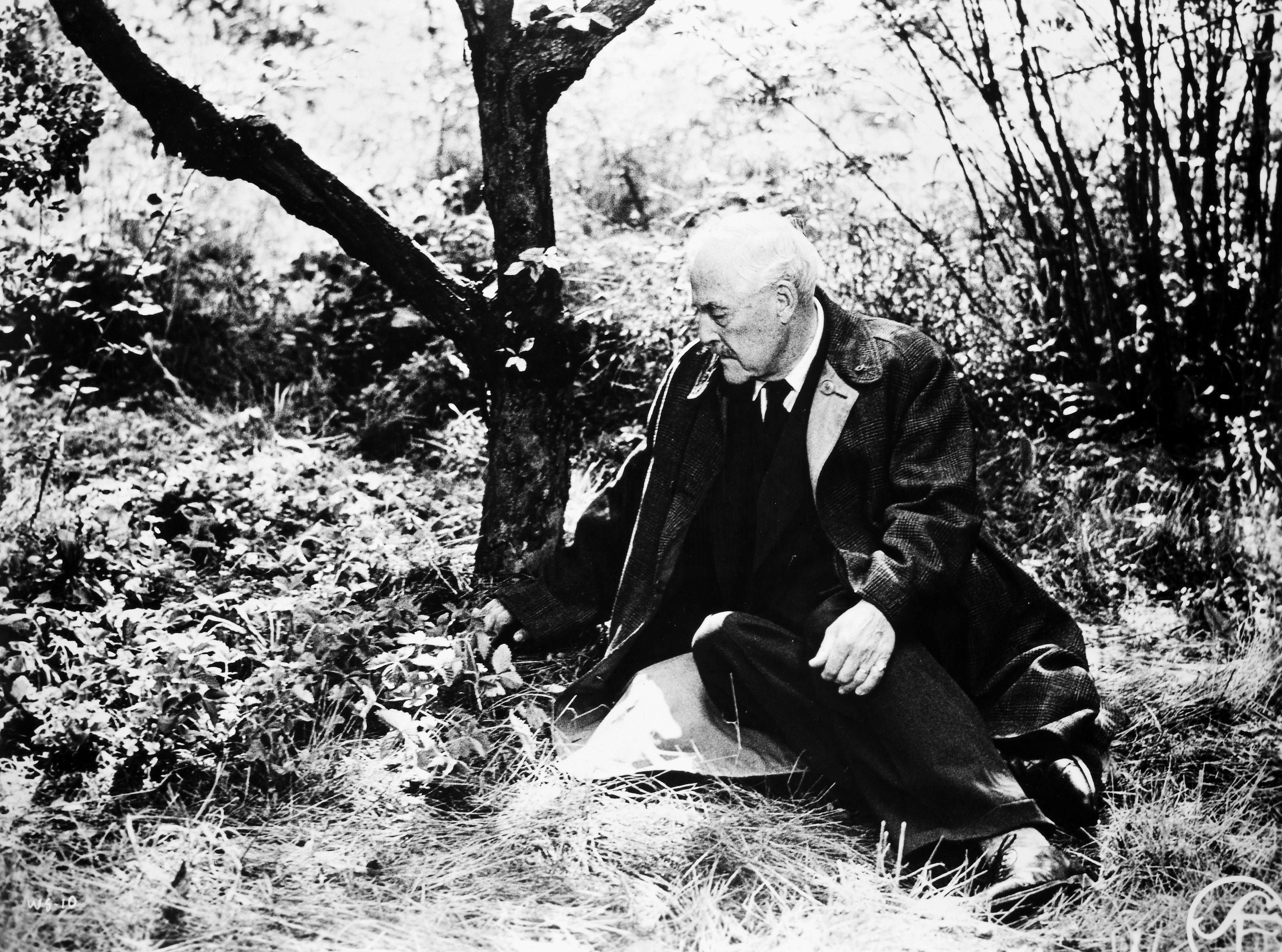

Time travel isn’t just for sci-fi and matinee romps either. Several reflective and introspective art house dramas have allowed ageing characters to venture back to their childhoods. For example, Ingmar Bergman’s 1957 classic Wild Strawberries has some lovely, wistful scenes in which the crotchety old professor (Victor Sjöström), who is coming toward the end of his life, is transported to the lost kingdom of his youth. On a far darker note, in Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), Clarence the angel gives James Stewart’s character, the small-town banker George Bailey, a nightmarish glimpse into the near future – and into the world as it might have been if he had not existed.

The great Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky famously described filmmaking as “sculpting in time”. “Time is a state: the flame in which there lives the salamander of the human soul,” Tarkovsky once wrote. In his films, especially in his masterpiece Mirror (1975), the storytelling isn’t linear. He is far more interested in his characters’ emotions and memories than in chronology. He leaps back and forth in time and includes incidents from his own childhood. His lyrical images of fields rustling in the wind and fires in forests are accompanied by evocative verse, written and recited by his father Arseny Tarkovsky, a celebrated poet. It’s a beautiful and very opaque movie – not a tall tale in which Indiana Jones is trying to keep sacred amulets out of Hitler’s henchmen’s hands.

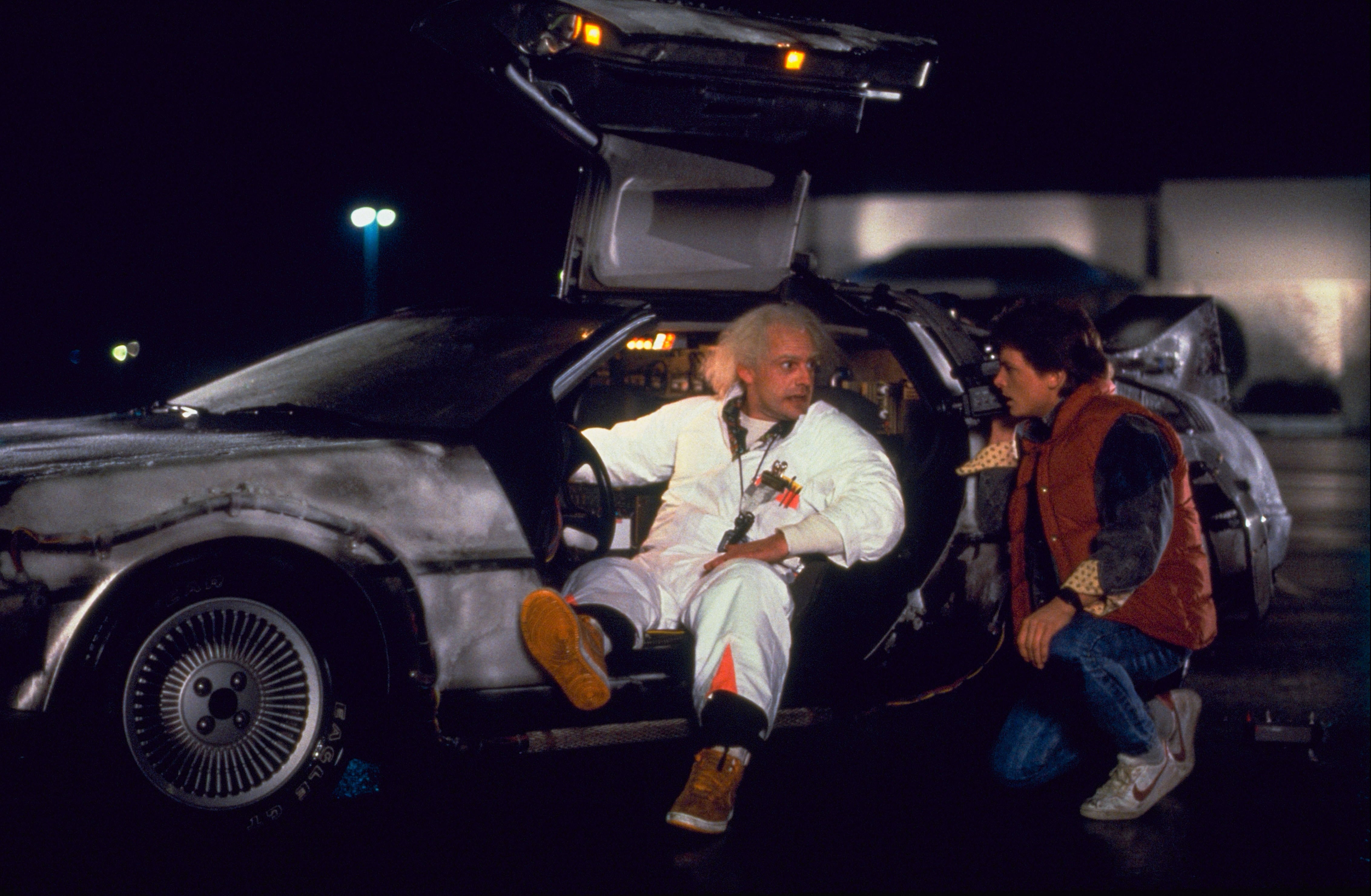

In a very different storytelling tradition, Robert Zemeckis’s funny and surprisingly subversive Back to the Future (1985) stands as Hollywood’s quintessential time travel picture. Its plot is very familiar. As he tries to escape Libyan terrorists, Michael J Fox’s 1980s skateboarding teenager Marty McFly is whisked back in time in a plutonium-fuelled DeLorean sports car travelling at precisely 88mph to 1955, the year when his young parents first came together. He meets his mother when she is still a very young woman and she disconcertingly develops a big crush on him.

Zemeckis isn’t just making an American high school version of the Oedipus saga. He is also able to squeeze out comedy from the smallest details, for example the bewilderment the 1950s suburban American folk feel about Marty’s 1980s clothes, in particular his red gilet, which they’re sure is a life jacket. Beyond its time travel elements, this is also a rite of passage story. It’s about Marty’s attempts to understand why his parents have turned out the way they have – what made his father so meek and submissive and his mother so reliant on alcohol.

Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris (2011) is another time travel movie that holds up well. A contemporary American screenwriter (Owen Wilson) stuck in Paris with his fiancée and her obnoxious right-wing parents, is given an intoxicating taste of the city in the 1920s when it is swarming with artists and writers. The director is both satirising and celebrating the hedonistic, bohemian world evoked in Ernest Hemingway’s memoir A Moveable Feast and in countless other books and dramas about Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, Pablo Picasso and co.

Romcoms often use time travel to engineer unlikely love affairs. “The secret is the men in this family can travel in time, more accurately back in time,” the laidback dad (Bill Nighy) tells his son Tim (Domhnall Gleeson) early on in Richard Curtis’s About Time (2013). All Tim needs to do is clench his fists and stand in a dark cupboard. He plans to use his new-found powers to get himself a girlfriend – a process that turns out to be far more fraught and complicated than he envisages.

In a similar vein, Audrey Niffenegger’s bestselling novel The Time Traveler’s Wife has inspired both a 2009 movie and a TV series last year. It’s easy to see why filmmakers are so drawn to it. It’s the story of a man with a genetic disorder that causes him to travel through time. Romance, sci-fi and philosophy are all thrown into the same heady mix without too much concern as to whether the plot hangs together or makes any sense.

As many of the films cited above show, time travel in movies doesn’t need to be a curse. The real trouble arises when filmmakers flagrantly break genre rules and deposit characters in periods far removed from their own. This is where The Dial of Destiny comes unstuck. It isn’t Interstellar, Back to the Future or The Time Traveler’s Wife. It’s an Indiana Jones movie. Audiences have expectations. It’s fine for Ford’s archaeologist to be racing away from boulders and clinging to runaway trucks or getting up close and personal with snakes, beetles, ants and other creepy-crawlies, but crashing through the fourth dimension is a step too far even for him. This is surely one case in which the filmmakers should have been told to stop the clock.

‘Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny’ is out on 28 June

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks