How to win an Oscar? Sex, spin and very dirty tricks

Harvey Weinstein may be gone, but the devious Oscar campaigning he masterminded remains alive and well. Geoffrey Macnab digs into the Academy Award manoeuvring that ensures the films with the biggest financial backing always come out on top on Oscar night

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Few today have heard of the 1997 Dutch movie Character, but it won the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar. So did Antonia’s Line (1995). At the beginning of the Noughties, the Netherlands produced further Oscar hits, earning nominations for dramas Twin Sisters (2002) and Zus & Zo (2001). Haven’t heard of those either? This streak was the product of a bit of Dutch film industry game-playing – having realised that the only Academy members with the time and inclination to actually watch international Oscar contenders tended to be at the end of their careers, the Dutch exclusively pushed tasteful, middlebrow dramas for consideration.

“In those days, [Academy voters] were all retirees, all older people,” says Claudia Landsberger, who was then the head of Dutch movie promotion agency Holland Film. They screened the films relentlessly and put ads in the industry trade magazines. “In those days, we could still have a party at the Consulate’s house. We’d have [Dutch filmmakers] Paul Verhoeven and Jan de Bont coming [to meet] all the Academy members.”

In the space of seven years, the Dutch racked up four Academy Awards nominations and two wins – and all for films that most of the general public outside the Netherlands didn’t even know existed. Their success cuts to an uncomfortable truth about awards campaigns. It isn’t necessarily the best films that win, but the ones that are marketed with the most chutzpah and cunning.

Sometimes, it can be as simple as choosing the right date – or dates. This year, many British audiences were puzzled by the decision to release Alexander Payne’s Oscar hopeful The Holdovers – a warm comedy-drama set around the Christmas break – towards the end of January in the UK. Particularly when it was first given a limited release in the US in late October, then a wide release two weeks after. But the protracted rollout in the UK was timed to the final round of Bafta voting, and the equivalent of the outsider in a horse race coming up on the rails. Everybody had been paying so much attention to bookie’s favourite Cillian Murphy for Oppenheimer that they were taken by surprise by the flood of late publicity on behalf of Holdovers lead Paul Giamatti.

In the end, Murphy won the Bafta, but both he and Giamatti had triumphed at the Golden Globes – in the Best Actor in a Drama and Best Actor in a Comedy/Musical categories, respectively. The awards buzz generated for The Holdovers also turned the film into a box office hit in the UK – something that may not have happened if it was released here any earlier.

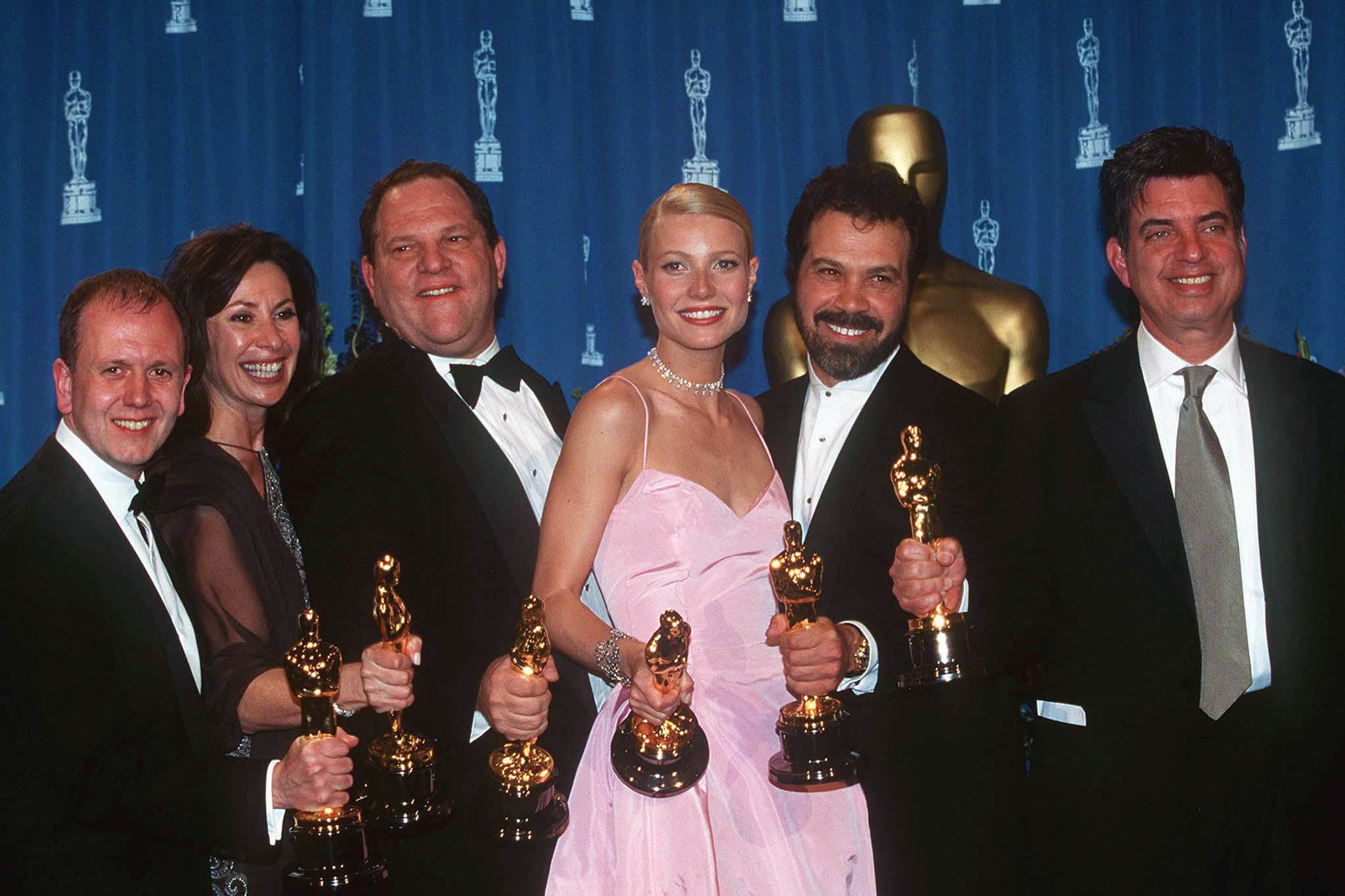

“Look, you have to keep it interesting,” the disgraced movie mogul Harvey Weinstein used to say about the annual Oscars scramble. Years before his sex crimes were exposed, Weinstein would famously go to extreme lengths to win awards for the films produced by Miramax, the studio he co-founded with his brother, Bob. In his book The Oscar Wars, author Michael Schulman reports in exhaustive detail the nefarious campaigning tactics Weinstein would deploy, most notoriously to ensure that Miramax’s Shakespeare in Love beat DreamWorks and Paramount’s Saving Private Ryan to the 1998 Best Picture Oscar. This included telling The New York Times that Saving Private Ryan rapidly went downhill after its famous beach landing opening scene. There were also reports of freelance Miramax publicists “totally trashing” Steven Spielberg’s movie to other journalists.

At one point in The Oscar Wars, Schulman describes how Weinstein borrowed campaign tactics from the political world to ensure his films came out on top. “By casting Ryan’s bravura D-Day sequence as a liability, Weinstein had channelled one of Karl Rove’s rules of the political dark arts: attack your opposition’s strength, not its weakness.”

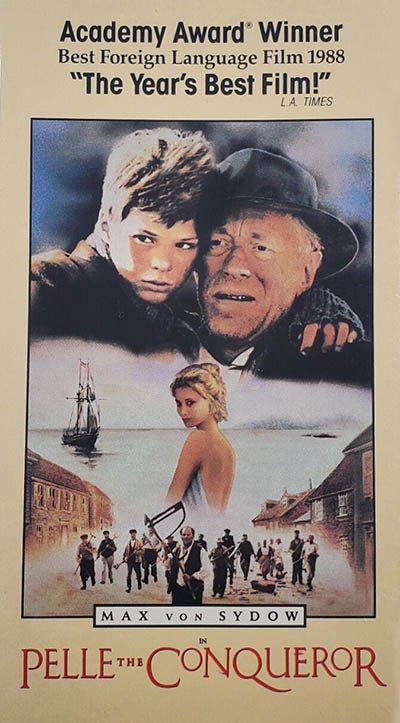

When it came to getting Academy voters on side for his movies, Weinstein was also no stranger to a “sex sells” approach. Early in his career, when he was tub-thumping on behalf of a bleak 1987 Scandinavian arthouse drama named Pelle the Conqueror, he issued posters foregrounding the nude back of a woman who barely appears in the finished film. It worked. The film won Best Foreign Language Film at the 1988 Oscars.

Later, when the company was promoting Neil Jordan’s The Crying Game (1992), about an IRA member who falls for a transgender woman, Weinstein and his team desperately tried to keep the film’s co-star out of the public eye. Jaye Davidson – the male actor who played the transgender character – was ultimately nominated in the Best Supporting Actor category, all but giving away the film’s central twist.

Gone are the days when you could effectively buy awards. This happened most notoriously with the Golden Globes in 1982, when millionaire Israeli financier Meshulam Riklis flew members of the Hollywood Foreign Press Association to Las Vegas. They promptly responded to Riklis’s hospitality by giving his young wife Pia Zadora a New Star of the Year award for her critically derided performance in steamy thriller Butterfly. The other nominees included Elizabeth McGovern for Ragtime and Kathleen Turner for Body Heat – but they were never in with a chance. “With her bee-stung pout and undulating child-woman hips, Pia Zadora is an American Bardot,” critic Rex Reed enthused about her performance. No one seemed to find it incongruous that this blatantly sexist quote was used in the campaign ads.

The “Pia Zadora scandal,” as it quickly became known, represented a nadir in awards campaigning. Nonetheless, there has been plenty of subterfuge and fast practice in the Oscars and Golden Globes races since then.

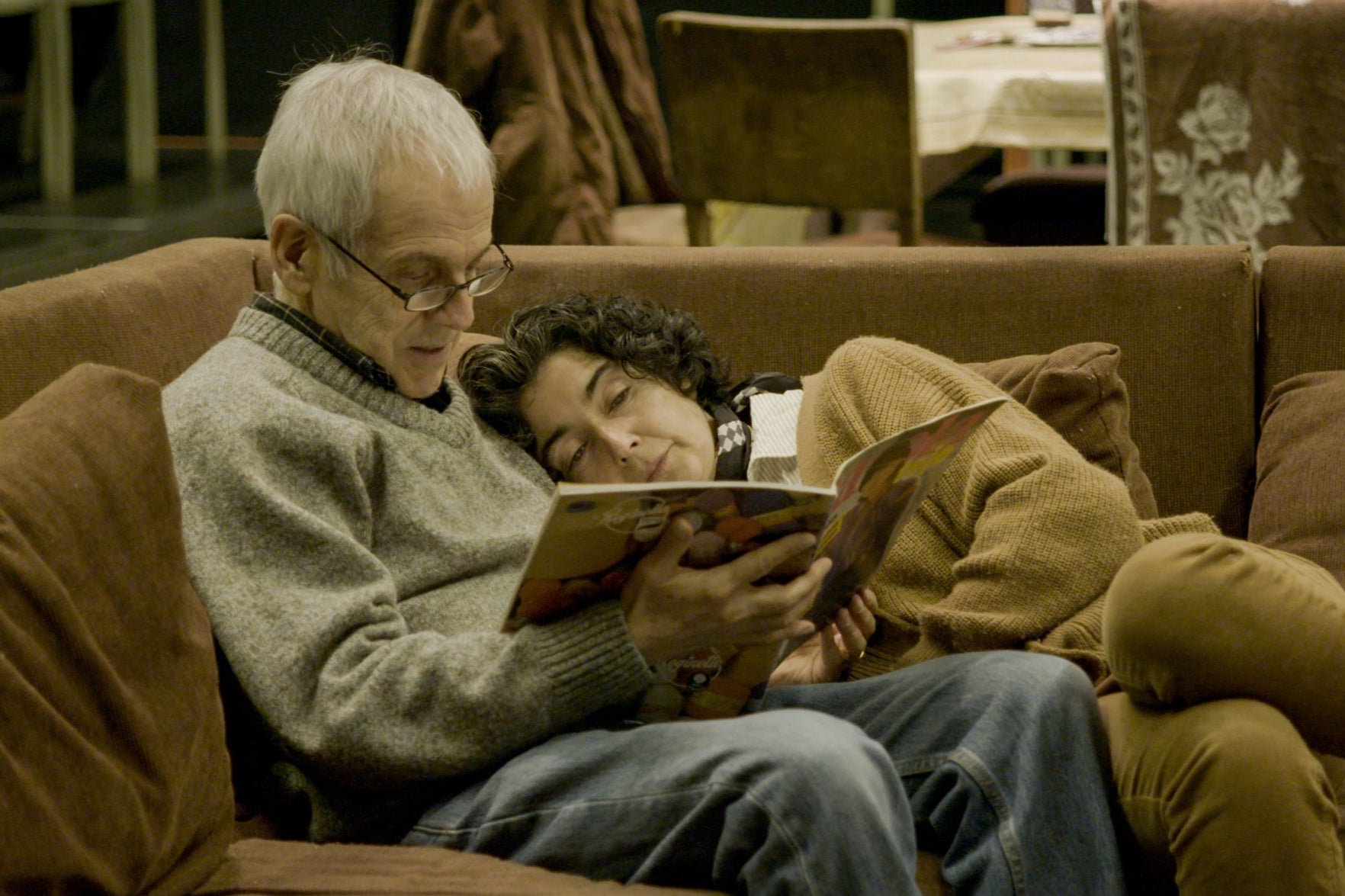

Whenever award campaigning rules are changed, they create loopholes that inventive filmmakers and distributors can exploit. The Chilean filmmaker Maite Alberdi received her second Oscar nomination this year for her feature documentary The Eternal Memory, a love story about a married couple affected by an Alzheimer’s diagnosis. Alberdi freely admits that her previous Oscar nomination, for her 2020 documentary The Mole Agent – which is currently being spun off into a drama series starring Ted Danson – was helped by Covid.

“The Mole Agent was an independent film,” she remembers. “We didn’t have the budget for a campaign but we got the nomination because the awards campaign was more democratic. Everything was online so you didn’t need the budget to make screenings in LA.” During the pandemic, Hollywood studios had nothing to splash the cash on. There were no lavish parties or swanky in-person screenings. It meant that smaller films were able to compete with the majors on equal terms.

As this year’s Academy Awards roll around, there have been the usual recriminations and backbiting about oversights and omissions. One point of contention are the so-called Barbie snubs, after Greta Gerwig and Margot Robbie missed out on Best Director and Actress nods, respectively. Champions of films including Ferrari, Saltburn, The Iron Claw, Asteroid City and Priscilla have likewise cried foul over their lack of nominations.

Do the best films win? Sometimes, but it certainly helps if they have spin doctors behind the scenes ready to talk up their merits, throw lavish parties and generally tub thump on their behalf. And quietly insisting to voters that, by the way, all those other contenders absolutely suck…

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments