How to Talk to Girls at Parties: Elle Fanning and Neil Gaiman on why this alien teenage romance is set in Seventies punk Croydon

The film’s been criticised for failing to capture the music scene, but director John Cameron Mitchell explains he just wanted to make a sweet story about love

“I wrote the short story How to Talk to Girls at Parties for 15-year-old girls and boys of all ages and genders,” says award-winning writer and American Gods creator Neil Gaiman.

Originally published as part of his short story collection Fragile Things in 2006, it’s the fantastical tale of a teenage boy who falls in love with a female alien in punk-era London.

Hedwig and the Angry Inch director and star John Cameron Mitchell has adapted the tiny tale into a feature-length film starring Elle Fanning as the teenage alien Zan and Nicole Kidman as punk bigwig Queen Boadicea.

The origin of How to Talk to Girls at Parties is autobiographical. Gaiman wanted to capture that period of adolescence when boys and girls have a love-hate relationship and the gap between the genders seems insurmountable

“That gulf where it seemed like only a couple of years ago we were climbing trees together and hanging out and now you’re wearing make-up and I feel these peculiar urges and I don’t even know how you got these breasts and this is all really weird,” recalls Gaiman. “And for you it must be weirder, as now I’m covered in spots, trip over things and got large, hairy and really irritating.”

Gaiman says the silver jubilee backdrop and celebration of punk is simply an accident of time: “If I was 10 years older I’m sure this story would be set in the summer of love. If I were 10 years younger it would probably be Manchester, and 20 years later would be Seattle. But I wouldn’t set it in those places, I’d set it on the edges where people are going: this grunge thing is happening and we kind of get it.”

That explains the Croydon setting then, which is where Gaiman lived during the 1970s.

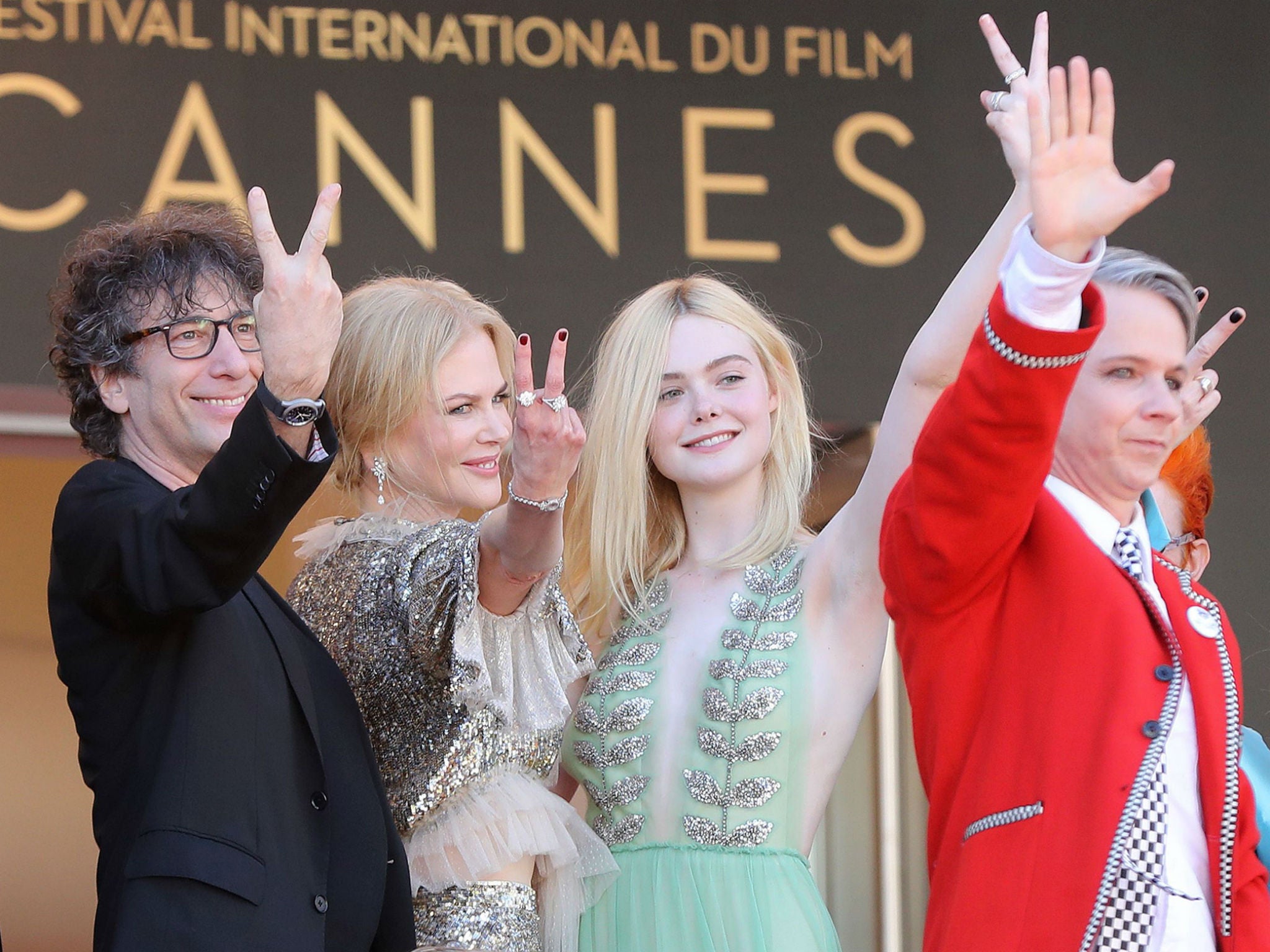

The anticipation that this would be a film about punk seemed to divide critics when the film premiered at Cannes Film Festival last year. Many argued that director John Cameron Mitchell had not captured the music scene, others that it lacked narrative focus. One critic even called it “one of the worst movies ever made”.

But other reviewers loved the sheer ecstasy of Cameron Mitchell’s creation, from Sandy Powell’s amazing costumes to the eclectic music choices. Hit songs are avoided in favour of The Damned, The Homosexuals, dub reggae and live songs from a fictional live band The Dyschords, created by Martin Tomlinson and Bryan Weller. The aliens are soundtracked by a fusion of Krautrock-inspired loops and classical samples.

So Cameron Mitchell confounded expectations that this would be about a music scene: instead of making a radical, edgy, realist appraisal of punk, he seemed to offend because his film is a sweet story of teenage lust and love.

“I wanted to make a pop film about love,” agrees the director. “All my films have to have love or be about the absence of it.”

He laughs at the criticism of the film not capturing the punk scene. It’s a sign of the times he argues, by which he means the present-day need to define pure subcultures that follow a set of regulations.

“That’s the funny thing about punk, just like everything else it starts to become rules. What are the rules? Suddenly you realise: doesn’t that actually go against the definition of punk?”

Cameron Mitchell laments the way that the internet has opened up access to music and yet the sheer volume of what is on offer has seemingly prevented a new musical sound breaking out into the mainstream.

“What was the last popular musical movement?” he asks himself rhetorically. “Grunge. Isn’t that weird? It was an Americanised version of punk. The Neil Young version of punk.”

“Around the year 2000, the mass music movement disappeared and it just became atomised,” he continues. “The end of style is 2000 because of the internet. It’s all in tiny groups now. It has wonderful plusses because you care so strongly about that group, but the negative side is that people only read the news that they want to see and they don’t believe any objective reality. William Burroughs was right, everyone is alone.”

Alex Sharp, who won a Tony award for his role as Christopher Boone in the stage adaptation of The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, plays Enn, the wannabe musician who attempts to woo Zan, played by Fanning, by trying to take her on a punk odyssey. Throughout the film Zan asks all and everyone: “What is punk?” The only answer she gets is “the fag end of the blues”, a line delivered by Kidman playing a band manager.

As for his own punk history, Cameron Mitchell admits “it was only after I came out that I got into punk. There was a kind of queer punk thing happening in the late Eighties and early Nineties, which led to Hedwig. There was a scene happening called SqueezeBox!, a party in New York with a queer punk scene.”

Cameron Mitchell introduced Fanning to the genre. “He’s the encyclopaedia of punk. You can get intimidated talking to him,” says Fanning.

Still, she has a completely opposite view to the director about how social media is affecting culture. “Because of social media I feel that young people are more informed and opinionated and free to speak their minds.”

She jumped at the chance of working with the director because she says he’s one of the most unique voices working in cinema today: “You know a John Cameron Mitchell movie will be out of the box and so emotional. John is such a soulful person, he’s so sensitive, but he also has a wild side.”

He also encouraged Fanning to come out of her shell: “You’re willing to push yourself because it’s John. He gets you into a mindset to just do it.”

And that seems about as punk as one can be.

‘How to Talk to Girls at Parties’ is in cinemas

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks