How Daniel Day-Lewis' notoriously rigorous role preparation has yielded another Oscar contender

Again, there's method in his madness. He talks to Chris Sullivan

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Anyone who has seen Daniel Day-Lewis in Paul Thomas Anderson's storming "big oil epic" There Will Be Blood might wager that the best actor Oscar is already his.

As the chillingly mercurial Daniel Plainview, a pioneering oil prospector who strikes it rich after discovering a lake of oil underneath New Boston, California, the actor owns the film for its two hours and 40 minutes. For the first 20 – in which not a word is spoken – he sustains a level of intensity that is truly astonishing. Day-Lewis has already received a Golden Globe and a Screen Actors Guild Award, plus top awards from almost every US critics circle, for his performance as the hard-bitten, irreligious misanthropic mountain of a man.

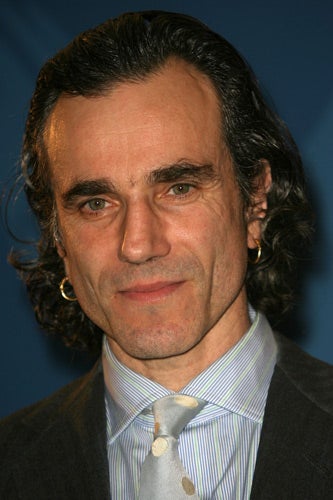

But, as the actor bounds into the room to meet me, he could not be more different from the toweringly obnoxious character he has created. Smiling for Ireland, the absurdly youthful 50-year-old is dressed like a traveller with a penchant for country and western, in checked shirt, jeans and a Mexican silver buckled belt, sporting shoulder-length wavy hair and two rather large silver hoop earrings. An affable, funny and down-to-earth man, without pretension, his rather charming old-school manners are given voice in an accent with more than a hint of an Irish lilt, as far from the clipped growl of Plainview as one could imagine.

Much of what is said about Day-Lewis is not to his liking. Journalists have written about his time on a film, his time off, what he does, how he does it. They have examined his relationships, his habits, his way of life. And here I am, about to do it again.

The reason for this level of interest is that Day-Lewis's work is big news. There Will Be Blood, loosely based on Upton Sinclair's novel Oil! (itself loosely based on the scandalous life of the barnstorming oil tycoon Edward L Doheny), has received eight Oscar nominations and met with a fanfare of critical acclaim. Some have suggested that, judging by this rivetingly physical rendering, Day-Lewis is the world's greatest living screen actor.

"I was working on this part for three years, but not in isolation, as Paul and I were in very close touch the whole time," says Day-Lewis, who was in character throughout the shoot. "My preference is that, that day when someone sticks a tripod in front of you with a camera on the top, it is not day one. It begins way before, with the work before you start filming – and there is no limit to the amount of time that you take to discover a whole life; it could take six months, a year, or a lifetime."

I first met Day-Lewis more than 20 years ago. A tall skinny young actor with a bleached Jimmy Dean haircut, he was, as he described, "working on a little film about a launderette and two gay blokes". Since then, Day-Lewis has made 16 films, established himself as one of the world's finest actors, won copious awards and fathered three boys: Gabriel, with his former partner Isabelle Adjani, the French actress; and Ronan and Cashel, with his wife Rebecca Miller, the daughter of the US playwright Arthur Miller and writer/director of the actor's previous picture, The Ballad of Jack and Rose. The couple have lived in the Wicklow Mountains in Ireland for the past 15 years.

The son of the poet laureate Cecil Day-Lewis and Jill Balcon (daughter of Sir Michael Balcon, the founder of Ealing Studios), the actor grew up in Greenwich, south-east London. He never allowed his privileged upbringing to get in the way of a life less ordinary. "A house full of great books about art and literature was all well and good, but I was fascinated by the streets that were close by – Lewisham, New Cross and Deptford. I supported Millwall with great gusto and was on the terraces every Saturday with the rest of the lads.

"It was such an important part of my life that, give my parents their due, they did not deprive me of. Even though their experiences were very far removed from what I was experiencing, in that neither of them would ever have considered setting foot on the terraces of the Den, both of them were completely open and believed that, as much as they were part of this society, there was work that had to be done to break down its rigid demarcations.

"It was through roaming the streets of Deptford that I started to understand this society we live in, which at the time coincided with a wave of dramatists who used the medium to break down the social barriers: Barrie Keefe [he cites Keefe's Gimme Shelter trilogy with Phil Davies as especially inspiring], Nigel Williams, Karel Reisz, Lindsay Anderson and of course my hero, Ken Loach, who can do no wrong as far as I'm concerned.

"Then, when [Martin Scorsese's] Mean Streets came out, I was 16, and you cannot imagine the effect it had on me, a young and slightly wayward guy from south V C London. It was like a light going on in my head. It was so influential for me as a young person, never mind as a young actor."

Little wonder that when the director Stephen Frears cast Day-Lewis as Johnny in My Beautiful Laundrette (1985), he excelled. "Here we have a Pakistani running a launderette, two gay boys and the National Front," he says, eyes twinkling. "My Beautiful Laundrette was truly outrageous and a continuation of this dramatic tradition of scrutinising this ludicrous divided society we inhabit. Hanif Kureishi [the writer] is the dog's bollocks and really puts the cats among the pigeons, Stephen Frears is a natural anarchist and I was a feisty young devil who loved anyone that stirred things up. It is a very sustaining feeling to feel that you are all partaking of this mischievous enterprise."

Of course, it's this mischief that makes him tick. Throughout his career, he has resisted classification and mesmerised critics and public with work where every role is bafflingly different and eminently challenging. "I did A Room With a View at the same time as Laundrette," he remembers. "I believe they premiered in New York on the same night. I relished the opportunity to do both – in Laundrette I was this working-class outcast, and in Room I was this upper-class twit. It was great fun."

The two roles established the actor on the international stage, but it was his Oscar-winning turn as Christy Brown in My Left Foot (1989) that won him a reputation as one of the world's foremost practitioners of the method school of acting. Throughout production, the actor remained in character as the writer with cerebral palsy, never leaving his wheelchair and being spoon-fed by the crew. "A few people did find that a bit odd," he admits, chuckling. "My agent Julian, who is sadly no longer with us, was quite unsettled when he came to visit me on set as I was 'in character' all the time and, apart from anything else, he couldn't understand a word I was saying. So he walked out, had a very quiet aperitif in a local hostelry, and from then on just left me to get on with it."

This preparation, for which Day-Lewis is now notorious, has been the cause of much heated discussion – and some public concern. He crudely tattooed his hands and trained as a real fighter, twice a day, seven days a week, for nearly three years, for The Boxer (1997). His trainer – the former world champion Barry McGuigan, no less – remarked that he could have turned professional.

For In The Name of the Father (1993), he slept in an abandoned jail and ate only prison rations. For The Crucible (1996), he lived in the film set's replica village without electricity or running water and built his character's house with 17th-century tools.

But it was his method work as Bill the Butcher in Scorsese's Gangs of New York (2002) that attracted most attention. He trained as a butcher, caught pneumonia while on set (having refused to change his threadbare coat for a warmer one because it hadn't existed in the 19th century), and wandered about Rome (where Gangs was filmed) in character, fighting strangers. "I had to do my preparation," he says with a grin. "And I will admit that I went mad, totally mad. I remembered the days of fighting on the Millwall terraces and they stood me in good stead for Bill the Butcher. He was a bit of a punk, a marvellous character and a joy to be – but not so good for my physical or mental health."

Day-Lewis plays down most of the rumours about his working methods, and is clearly sick to death of hearing them. "For me, it seems obvious, as that is what I do," he stresses, sounding baffled. "And I think, 'Well, if people think it's odd, then what can I do?'"

One soon realises that it is Day-Lewis's quest for perfection that allows him to take on these different roles, these lives, and (apart from his family) that is what he lives for. "You go to these great lengths to imagine another world and time and imagine a man, like Plainview, living in those times – and having spent your imagination on that, it seems more fun to live there all the time than jumping in and out," he says. "That is the playground you've created, so why not stay there and play? It gets rid of that notion of playing between times, which often people talk about – waiting for the next shot. I don't buy that. Whatever you can do to give yourself a sense of continuity can only add to the work.

"I have always been intrigued by these lives I have never experienced. And I love the pure pleasure of doing the work, no matter if that work involves some kind of discomfort – even though I don't see it as that, one just deals with the day-to-day challenges of the character. I do it out of curiosity and I enjoy it. But the way people would have it, it is like a game of self-chastisement and it has never been that way for me – it's all just a big, funny game."

For Michael Mann's The Last of the Mohicans (1992), the actor was able to prepare for the role of James Fenimore Cooper's 18th-century hero Hawkeye by living off the land for six months, learning how to hunt, fish and skin animals. But where did this jovial, happily married family man find the seething ferocity of Plainview?

"Well, we all have murderous thoughts throughout the day, if not the week," he replies with a wicked glint. "We all live under some repression; we have to, it's part of the deal. And what is more invigorating than to unleash some of that stuff? But I cannot account for where any of this comes from. It comes from the unconscious and I cannot account for what ferments in my unconscious. That part of the work doesn't take part in the conscious; one just hopes there is a cave somewhere in your mind that you can ransack.

"But so much of the work relies on consciously allowing things to emerge in spite of yourself," he adds. "Consciously always looking for the instinctive – that animal part of yourself – and even though somewhere inside you sculpt and organise with some reason, there is always something a little more chaotic going on."

So engrossed was the actor in the role that, when asked how long the shoot was, he answers: "I don't know – maybe 12, 14 weeks. I really couldn't tell you. But the joy about great work is that you are not looking for the finishing line. Quite the opposite. As with all artistic endeavour, you lose yourself; it's like time out of time, a period when I lose myself and the clocks stop."

How do the wife and kids cope with having a father who, for long periods, is someone else? "For There Will Be Blood, my wife and kids were with me throughout," he replies. "And they did go a little bit crazy living with Plainview all the time, but the kids thought it was a laugh in the end to have this different bloke as their dad and both did a pretty decent impersonation of me. My wife is amazingly tolerant. I knew that from the word go. She just believes, like I do, that if you are attempting anything of a creative nature, no rules apply."

One of the hardest things for Day-Lewis is letting go of the characters he has so lovingly created. "Well, absurd as it might seem, when you've been someone else for that amount of time, it's even more absurd when it's all over." He laughs. "Then the joke is on all of us, because once a curiosity is unleashed you can't just tie it up again. It does take time to let go. There is no great part of you that wants to stop doing that work, and no matter how much you're begging for it to stop you need someone to put a restraining order on it."

Luckily for me, on the day we met, Plainview had long since vacated the premises.

'There Will Be Blood' opens on 8 February

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments