How a new biopic reveals another six sides of Bob Dylan

Todd Haynes took on the challenge of a lifetime by making a film about the legendarily enigmatic troubadour. The resulting biopic is almost as hard to pigeon-hole as the man himself

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There are biopics and biopics, but nothing remotely like I'm Not There, Todd Haynes's hall-of-mirrors life of Bob Dylan or rather his fantasia on, as the credits specify, "the music and many lives of Bob Dylan". Whether or not Haynes's film "works", whether or not it "makes sense", whether or not it "tells" you anything specific about its subject, this is as bracingly strange and ambitious a project as American cinema has produced in a while.

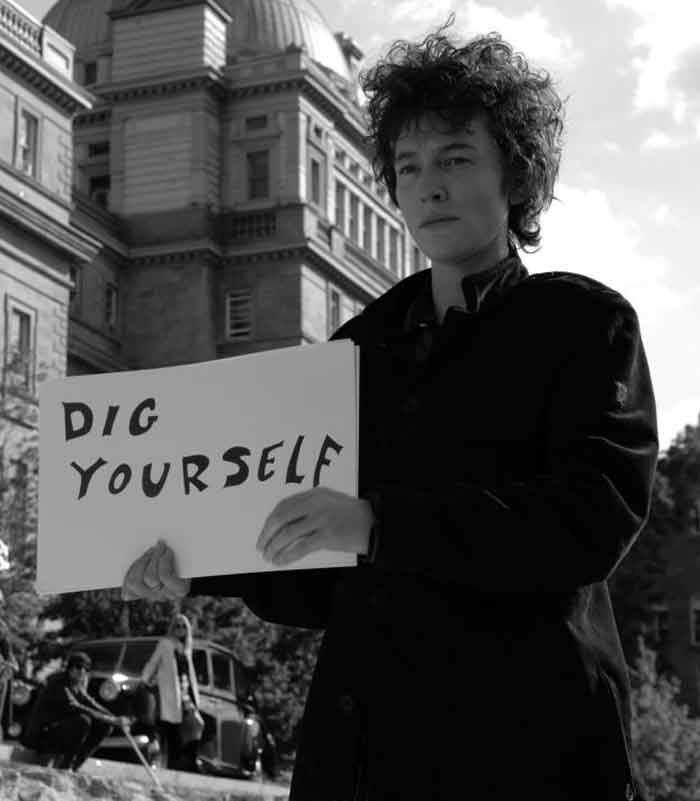

Haynes's last flirtation with music was 1998's Velvet Goldmine, inspired by David Bowie and the glam-rock years. In I'm Not There, Haynes reclaims Dylan as a proto-Bowie chameleon, even in Cate Blanchett's turn as a skeletally androgynous Sixties rocker as a Thin White Duke avant la lettre. Six actors "play" Dylan, after a fashion, each embodying one or more of his personas over the years. Blanchett dons the shades and spidery threads of the mid-Sixties hipster as Jude Quinn, a rocker wearied by adulation, hostility and the "Judas" brickbats endured while touring Britain. A breathtakingly canny, genially brash 11-year-old black actor called Marcus Carl Franklin represents the embryonic folkie, here calling himself Woody Guthrie after his hero, and living out anachronistic fantasies of being a Depression-era boxcar hobo.

Christian Bale, at his most forbidding and wiry, plays Jack Rollins, a protest singer who retreats into hellfire preaching, evoking the born-again Dylan of the early Eighties. Heath Ledger now here's where it gets complicated isn't strictly Dylan at all, but Robbie, a movie actor who once played Jack Rollins in a biopic called Grain of Sand (the film that, we're to understand, Haynes's defiantly isn't) and whose relationship with French painter Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg) echoes Dylan's spells with both early Sixties girlfriend Suze Rotolo and his former wife Sara. Ben Whishaw also contributes gnomic one-liners as a figure who's half Dylan, half Arthur Rimbaud the poet whose formulation "'Je' est un autre" (which roughly translates as "It ain't me babe") pretty much serves as the film's founding principle.

True to Rimbaud, Haynes the director is never remotely "himself" in the film. Just as the film resembles an oddly selective Dylan compilation set on shuffle, tentatively gesturing at linear biography while scrambling and distorting it, Haynes's own style zips around crazily: one moment he's pastiching D A Pennebaker's Dylan documentary Don't Look Back, with additional splashes of Fellini, Godard and Richard Lester (there's a lovely Beatles-as-Chipmunks gag here); the next he's illustrating "Ballad of a Thin Man" in disconcertingly literal MTV style. As for Robbie and Claire's divorce, it's set in a domestic-realism mode that may or may not be deliberately evoking the banality of Kramer vs Kramer.

While most of the film is just about readable as an imaginative version of Dylan's actual life, the segment that's truly an inscrutable curveball and that will be a deal-breaker for many viewers is the Richard Gere section. Booted and grizzled, he plays a country loner who conflates Billy the Kid and the taciturn character that Dylan played in Sam Peckinpah's 1973 film about the outlaw. Living in a dream version of Dylan's country retreat of the Sixties, he visits a town called Riddle that feels like Rimbaud's idea of the Wild West; peopled by carnival costume acts, kids wearing tumbleweed, and stray zoo animals, Riddle seems to be a visualisation of the free-associative rambles of Dylan's liner notes. Either you'll be entranced or you'll find yourself screaming "There must be some kind of way outa here", but you have to admire Haynes's nerve in insisting that this strand be taken as an integral part of the whole. With the rest, you can just about feel you're getting the drift, but the "Billy" section throws the whole thing defiantly askew.

I'm Not There is not easy to describe, but it's still easier to describe than evaluate. You see how Haynes and co-writer Oren Moverman operate, but it's harder to determine exactly what the film is attempting, or whether it succeeds. The one certain thing to say is that Haynes is taking his belief in fragmentation and fluid identity to the absolute extreme justifiably so, given a subject whose career is arguably the most fragmented and fluid in American art. Whether or not the hardcore Dylanolaters will approve, lovers of his music can only be impressed by Haynes's intelligent avoidance of the obvious jukebox factor. For a start, he's chosen to name his film after an extremely obscure song from the Basement Tapes era. (Stick around through the end credits to hear a thunderous Sonic Youth version.) Among the unexpected gems from the songbook, there's a heartrending version by singer Jim James of "Goin' to Acapulco" and Dylan's own poignant, forlornly apocalyptic "Blind Willie McTell", when the child Woody goes to visit the real, dying Woody Guthrie in hospital.

In fact, the nearest we hear to a Greatest Hit is right at the end, a snatch of "Mr Tambourine Man" and then it's just a sweetly lugubrious harmonica coda played by Dylan, glimpsed himself for the first time in the closing fragment of Sixties footage. Do we know him any better by then? Hardly. The enigma remains intact, and if anything, becomes richer and stranger.

As for Todd Haynes, it's hard to see how he'll top this film's sheer audacity but there's a musical about Thomas Pynchon that's just begging to be made.

Life in tracks

The Dylan Renaissance began in 1997 with the release of 'Time Out of Mind', his 30th studio album, hailed as his best work since 'Blood on the Tracks' in 1973. Hot on its heels came the album 'Love and Theft', inspired by the singer's love of older American music genres. That interest was further exploited in a new career as a DJ on Digital XM's 'Theme Time Radio Hour', now imported by the BBC. A memoir, 'Chronicles', showed him for the first time as a fine stylist in prose, and 2006's 'Modern Times' made him the oldest artist ever to reach no. 1 in the album charts.

Further reading 'Chronicles, Volume One', by Bob Dylan, Pocket Books, 7.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments