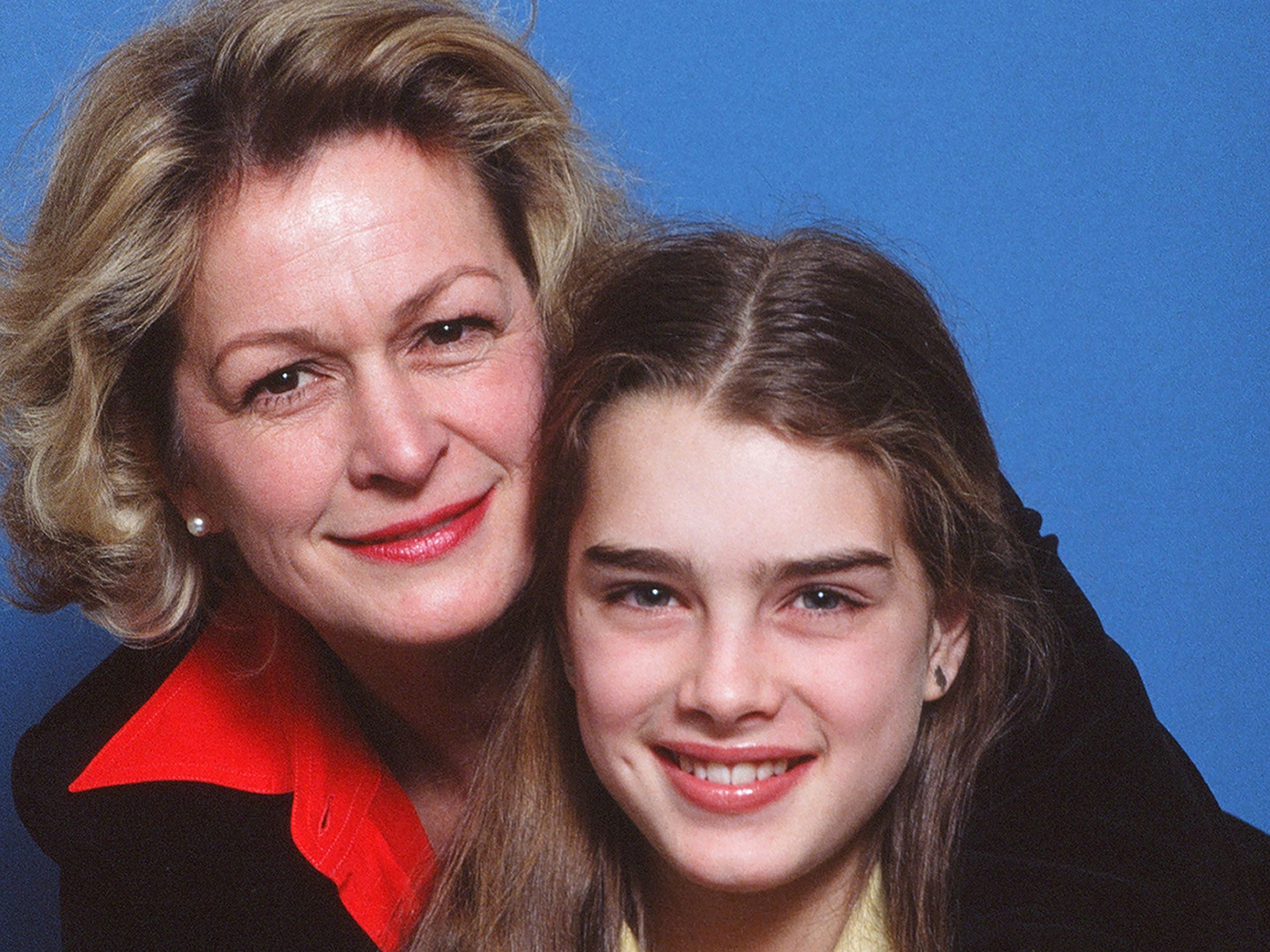

Hollywood moms: Were Brooke Shields and Judy Garland's pushy parents really that bad?

The parents of young female actresses attract suspicion from the outside world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.To the outside world, they are figures of ridicule and suspicion, blamed for pushing their daughters into movie careers at an absurdly young age, taking their money and basking in their reflected celebrity. They’re accused of stealing their kids’ childhoods and are blamed for whatever emotional or career problems those kids might suffer in later life. The truth about these “Hollywood moms” turns out to be far more complicated.

The recent publication of Brooke Shields’ autobiography There Was a Little Girl has put the role of the Hollywood mom back in the spotlight. Shields’ book is less about herself than about her mother, Teri Shields, a figure who from a distance seemed like the archetypal stage mother, pushy, manipulative and not as solicitous of her daughter’s welfare as she should have been. Shields, though, resists the “venomous” caricatures of the obituary writers (her mother died in 2012). Her portrait of her mother is nuanced and sympathetic. She doesn’t skimp on details of Teri’s alcoholism or her erratic and sometimes abusive behaviour but she provides context and perspective. Shields places her mother at the centre of the book rather than treating her as a bit-part player in her own story.

Other moms of former young stars have not been dealt with so kindly. Hollywood, celebrity gossip columnist Lloyd Shearer once wrote, “has long served as a refuge for widows, divorcées, hookers, the deserted, the dispossessed and the disappointed. For years mothers have brought their daughters here – Loretta Young, Betty Grable, Lana Turner, Betty Hutton, Judy Garland are just a few who quickly come to mind – hoping, plotting, scheming, working to wedge their progeny into the film industry.”

The implication was clear. The moms, newly arrived in Hollywood, regarded their kids as their golden tickets and hoped to achieve money and success through them.

When Shirley Temple, the biggest child star of all, died last year, the cautionary tales about her lost childhood were quickly recycled. Her mother Gertrude was the villain of the piece. She had allowed little Shirley to appear as a child of four or five in “Baby Burlesks,” a series of short satirical films which the actress herself later described as “a cynical exploitation of our childhood innocence”. There are grim stories about kids who misbehaved during filming being made to sit on a large block of ice to cool off. Her mother was accused of “shaving” a year off her age to make her appear all the more precocious. “Shirley would be shocked to discover, at a party for her 12th birthday in April 1941, that she was actually 13,” Temple’s New York Times obituary noted.

Look a little more closely and you discover that Gertrude wasn’t quite the Cruella de Vil-like monster, browbeating her dimple-chinned child, that so many accounts have suggested. As Temple herself later testified, “she was quite shy, but she always believe that if a door opens for you, go through it. She did not push me into anything. I loved what I did. I remember cruel mothers who would pinch their children to make them cry in a scene, but my mother encircled me with affection.”

Gertrude did enrol her daughter in dance school at the age of three and closely micro-managed her movie career. She was single-minded and sometimes ruthless, “no namby-pamby” as Shirley acknowledged, but she also went to great lengths to protect her daughter from the side-effects of fame. She tried to convince Shirley that film-making was simply “play acting and make believe,” and not to be taken too seriously. It is telling that, in spite of the way her film career unravelled as she grew older, Shirley did not end up like the grotesque, ageing child actors played by Joan Crawford or Bette Davis in What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? Her unlikely later incarnation as high-level diplomat – and as the US ambassador to Ghana and Czechoslovakia – suggested that Gertrude’s child-raising techniques (about which she once wrote a book) had worked after all.

Ethel Gumm, mother of Judy Garland, is another Hollywood mom accused of mistreating her daughter. Garland’s biographer Gerald Clarke revealed that Ethel, a small-time vaudevillian, gave Judy pep pills and sleeping pills from the time she was 10, to help her cope with life on the road. This must have helped foster Garland’s later drug dependency. Garland was said to have called her mother “the real Wicked Witch of the West”.

Many accounts portray Ethel as the quintessential domineering stage mother, relentlessly and recklessly pushing her daughter to achieve the success and fame that had eluded her. There is a measure of truth to this, but Garland herself is also quoted as saying that Ethel was strong-minded but never a “stage mama” as such. “She was part of an era that was hard on women,” Garland said. “Mother had to succeed at whatever she undertook.” Clarke, meanwhile, describes Ethel as “tirelessly energetic, unconquerable in spirit.” Like many other Hollywood moms, Ethel was a far more complex figure than the depictions of her as a “fire-eating, greedy, ambitious, stage matron” in Jeffrey A Kottler’s book Divine Madness suggest.

The same can be said of many of the other mothers who managed their daughters’ careers and drove them to become stars. These were tough and ruthless women who had often faced hardship in their own lives – but that doesn’t mean they deserve to be demonised. In the silent era, Charlotte Hennessey Smith, mother of Mary Pickford (“the girl with the curls”), was instrumental in managing her daughter’s career and making her one of the best-paid stars in Hollywood history. More recently, when Jodie Foster won a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2013, the first person she thanked was her old manager, who had plotted her career and decided which movies she would make from when she was four years old onwards. Who was this manager? It is no surprise to discover that it was Brandy Foster – her mother. Who else?

Brooke Shields’ ‘There Was a Little Girl: The Real Story of My Mother and Me’ is published by Dutton Press

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments