Helena Bonham Carter on working with kids, the 'always on' culture and 'golden opportunity' in Nick Hornby's TV show

Helena Bonham Carter tells Tom Atkinson that filming near home wasn’t the only reason she said yes to a new BBC comedy – after all, it is written by Nick Hornby. But it did help

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

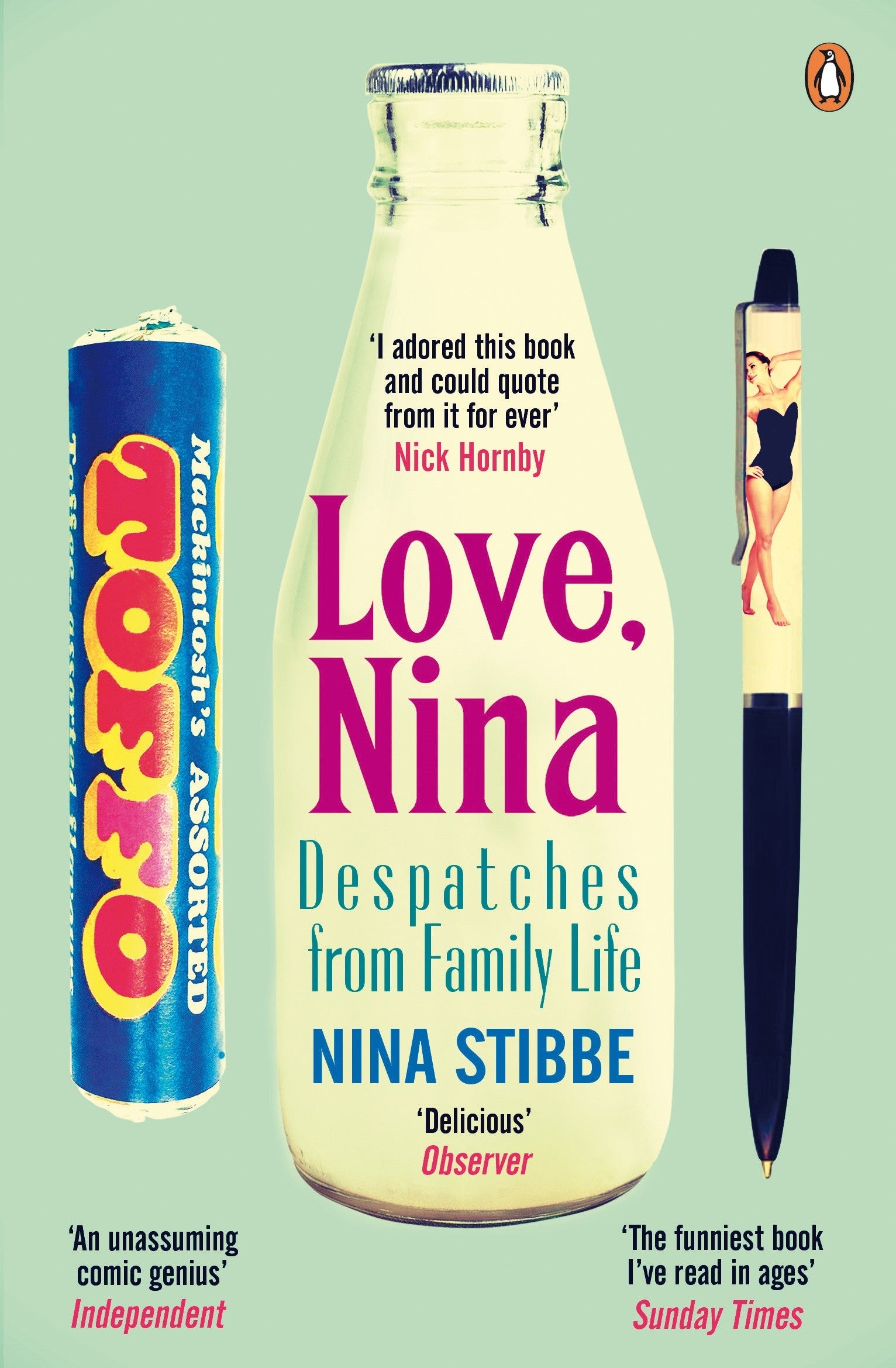

Your support makes all the difference.Nina Stibbe’s collection of letters to her sister became a surprise bestseller when it was published as Love, Nina in 2013, but it almost didn’t happen.

The book, which follows Nina’s life in the 1980s as nanny to London Review of Books editor Mary-Kay Wilmers’s two children, faced Wilmers’s initial reaction which was: “Christ, no, don’t publish!”

It has now been transformed into a five-part BBC drama starring Helena Bonham Carter – although Wilmers, whom she portrays, still had her reservations.

“I could sense that she probably felt a bit ambivalent about being played,” Bonham Carter concedes. “Although I did say I would only do it if I got her blessing, and if I could keep the swearing in. I got the first, but I didn’t really get the second!”

Wilmers needn’t have worried though, because, in addition to being portrayed by the twice-Oscar- nominated Bonham Carter, the story has been adapted by Nick Hornby, making his first foray into TV after his own Oscar nomination for the Brooklyn screenplay.

Bonham Carter has form for playing real people, having starred as Enid Blyton, Elizabeth Taylor, and even TV chef Nigel Slater’s stepmother, on the small screen, but with Wilmers the only one on that list still around to pass comment, the role required handling with care, as well as a name-change from Mary-Kay to Georgia.

“I met Mary-Kay and said: ‘Well, what shall we call us?’ I’d said to her by then, ‘whoever I come up with won’t be an impersonation of you, because now we’re renamed, that liberates us’. She is quite a reserved character, and she is an editor, she retreats, she is somebody who likes putting other people on show rather than herself.”

That’s certainly about to change with Love, Nina, but Bonham Carter says she’s well placed to portray the reputedly formidable editor.

“Somebody I met 18 months ago said, ‘you should play Mary-Kay!’,” she recalls. “Really, I had never heard of her because I hadn’t read the book. Well, when I got to know Mary-Kay and read up on it there is a lot that we share. We come from a very similar extraction, from my mum’s side, Jewish-European.

“Her mother was Russian and her father American but she was brought up in Belgium, and my mother is French so we had the same upbringing where, at home, French and English were interchangeable within a sentence, a patchwork.”

The two women share more than a Francophile upbringing, with Bonham Carter pointing out Wilmers’s marriage to Stephen Frears as a parallel to her own recently ended relationship with Tim Burton.

“We are both divorced from film directors, both with two children. I could relate a bit to it because Sam Frears is disabled and my father was very disabled so there was a sympathy there.” Mary’s eldest son, Sam, lives with a rare, debilitating condition, familial dysautonomia (FD), or Riley-Day syndrome, while Bonham Carter’s father uses a wheelchair following a stroke.

Her reference to film directors could indicate a tricky subject considering the endless tabloid speculation around the 13-year relationship with Burton that ended amicably in 2014.

Bonham Carter recently put paid to reports that the couple had always lived separately in adjoining houses by calling it “a load of myth”, but one director she is happy to discuss is the BBC’s choice to take charge of Love, Nina.

“SJ was the big pull,” she says of SJ Clarkson, the director who recently took charge of dark Netflix comic-book series Jessica Jones.

“We got on very well and we had the same taste. So when she had been approached, I knew that she would have the right aesthetic and I would be in the right hands. SJ is a visionary, so I just thought that she would capture the world that Nina has written.”

That world is one where Alan Bennett often popped round for tea and Jonathan Miller lent out his saw; a literary “who’s who” of the 1980s set around Wilmers’s kitchen table.

Stibbe, a 20 year old newly arrived in London from Leicester, hadn’t heard of any of them, and, while the book is littered with lightly-dropped names, you won’t hear many of them in the TV version because, as with Wilmers, identities have been changed.

“Everything morphed, like a domino effect,” Bonham Carter says. “Everyone had the normal names, then Alan Bennett suddenly said he didn’t want to be represented on telly. So they had to come up with another character, a playwright called Malcolm, so he comes to visit for dinner instead of Alan.

"I don’t know what it was, but it was a tear-up basically, so [we thought] let’s just change everybody’s name so no one can come and sue us!”

So you may not get to see another take on one of the world’s most impersonated writers (the ever-excellent Jason Watkins plays his stand-in, Malcolm), but one name that hasn’t changed is Nina’s. Game of Thrones’ Faye Marsay plays the young nanny and, as Bonham Carter flicks through images from filming on her phone (“there she is knackered, there she is asleep”) it becomes apparent that the younger woman had to suffer for her art.

“What I did was I rolled out of bed, rolled into the car and rolled into the make-up chair,” Bonham Carter admits. “Faye was amazing. She was The Waif in Game of Thrones on the Monday and on Tuesday she started this.

“So she was practically dead from day one and hypothermic because Nina said that she was barefoot. Then I asked Mary and Sam the other day, ‘was she barefoot?’. They said, ‘once or twice but not for six weeks’!”

In addition to working with Marsay, Bonham Carter was surrounded by the actors playing her children and their friends, and while she dismisses the old adage that you should never work with children, she says she wasn’t afraid to keep them in line.

“Well, of course they’re not your children so you forget to look at them sometimes. But then again you forget to look at your own children,” she admits. “The things is, with film, you’re always asked to look at people because of eye lines and everything, but the fact is with a family and me, a lot of the time you’re never looking at the person. You hold somebody and you touch somebody – that physicality. They were very good though, they were very easy and they had a lot of energy.

“I was quite disciplined. I suppose because I have got kids I could be quite abrupt with them without hurting them. Because we had to concentrate. It was very important.

“The trouble is, when you’re acting with kids, its not the acting on screen, it’s just before. And what happens is they’re farting around and they’re fine, but basically your concentration is thrown and you can’t do it because they’re chatting about anything but the scene and you’re desperately trying to work out where you come from or what you’re supposed to be concentrating on. That is where you have to protect yourself and try to get them to start listening.”

She praises her young co-stars’ talent though, even if she does remain cautious about developing close bonds with the children with whom she works.

“Sometimes you do [make] some friendships, but it is such a gypsy-like existence and then you go off to your own family or your very busy life,” she says.

“I think that a lot of the time what can be tricky is if you get too close to someone on the film and then they expect that friendship to extend and I can’t because I have my own children and a legion of friends who I let down daily anyway. I have a waiting list of friends who I should look after, so you have to be careful what you invite.”

Bonham Carter was a 17-year old schoolgirl in 1983, when the show is set. As she reminisces over the music she listened to (Edith Piaf and Charles Aznavour, but also Supertramp and Talking Heads) she admits to a fondness for the period, but says she was never a letter-writer like Nina.

“It’s a practically extinct form isn’t it? It’s terrible,” she says. “I write very few. I’m not very social-media savvy. I have never tweeted; I wouldn’t know how to tweet. I don’t have the time. I find my life is interrupted enough by every text, every email.

“Everybody requires some kind of connection and I feel like I can’t do anything.

“I had a lot of nostalgia for the Eighties and I was lucky because I had a happy childhood, but I think I would have loved the fact that we could just sit and not answer the phone,” she admits.

She goes on to bemoan today’s “always on” culture (“we haven’t got any stillness any more”) and the permanent presence of smartphones, admitting that Love, Nina represented a golden opportunity to film close to home and maintain a normal life, even if, thanks again to Alan Bennett, it didn’t quite work out that way.

“In my head, when they asked me to do it, I thought, ‘oh, Gloucester Crescent, that’s half a mile away from me, I could do the school pick-up, just dribble out of bed, it’s fine!’ But, very quickly, they said, ‘well, we can’t film in Gloucester Crescent because of The Lady in the Van’, the bane of our lives!

"So we were banned from Gloucester Crescent, so suddenly it was Islington, so OK, that’s not far.

"Then, they said, ‘we can’t film in the house, it’s not big enough for the equipment’. Oh yeah, D’oh! You’d have thought by now they’d have worked that one out. So the set, the kitchen, it was like being in Big Brother, you just wanted to get out. Four or five weeks round the kitchen table was in Stratford, not so local!”

Still, it did allow Bonham Carter to go home after work every day, and, while her next projects include more real life alongside Vera Farmiga in 55 Steps and a reprisal of the Red Queen in the Tim Burton-produced Alice Through the Looking Glass (her Steve McQueen-directed HBO series Codes of Conduct has reportedly been shelved), she says that quality is one of the main deciding factors when it comes to taking any job.

“Practically one of the first things, apart from the quality of the script, is if it demands any time away from the kids,” she says.

“It limits the choices. I haven’t been away from them for more than two weeks since they were born so that is [over] 12 years. I don’t know if they’re any better for it.”

This, coupled with the brilliance of the original book, made for one of Bonham Carter’s most personally satisfying projects to date.

“I read it quickly and I found it enchanting,” she says. “I thought, ‘well, this just makes me happy’. If we can do this on the telly… if telly is happy- making then it is worth making.”

‘Love, Nina’ will be aired on BBC1

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments