Ghost World at 20: ‘In an era of teen comedies and American Pie, this was an antidote’

Based on a caustic comic book, the high-school movie has become a cult classic in the two decades since its release. Rick Burin talks to its star Thora Birch, director Terry Zwigoff, and comic creator Daniel Clowes about the film’s inception, filming and lasting legacy

I thought I was never gonna work again,” says Thora Birch. “Honestly, and I hate to say this now, because I don’t know what I was thinking, but I thought it was really boring.” She laughs. “‘Who the heck is gonna give a crap about this bratty little bitch?’, you know?”

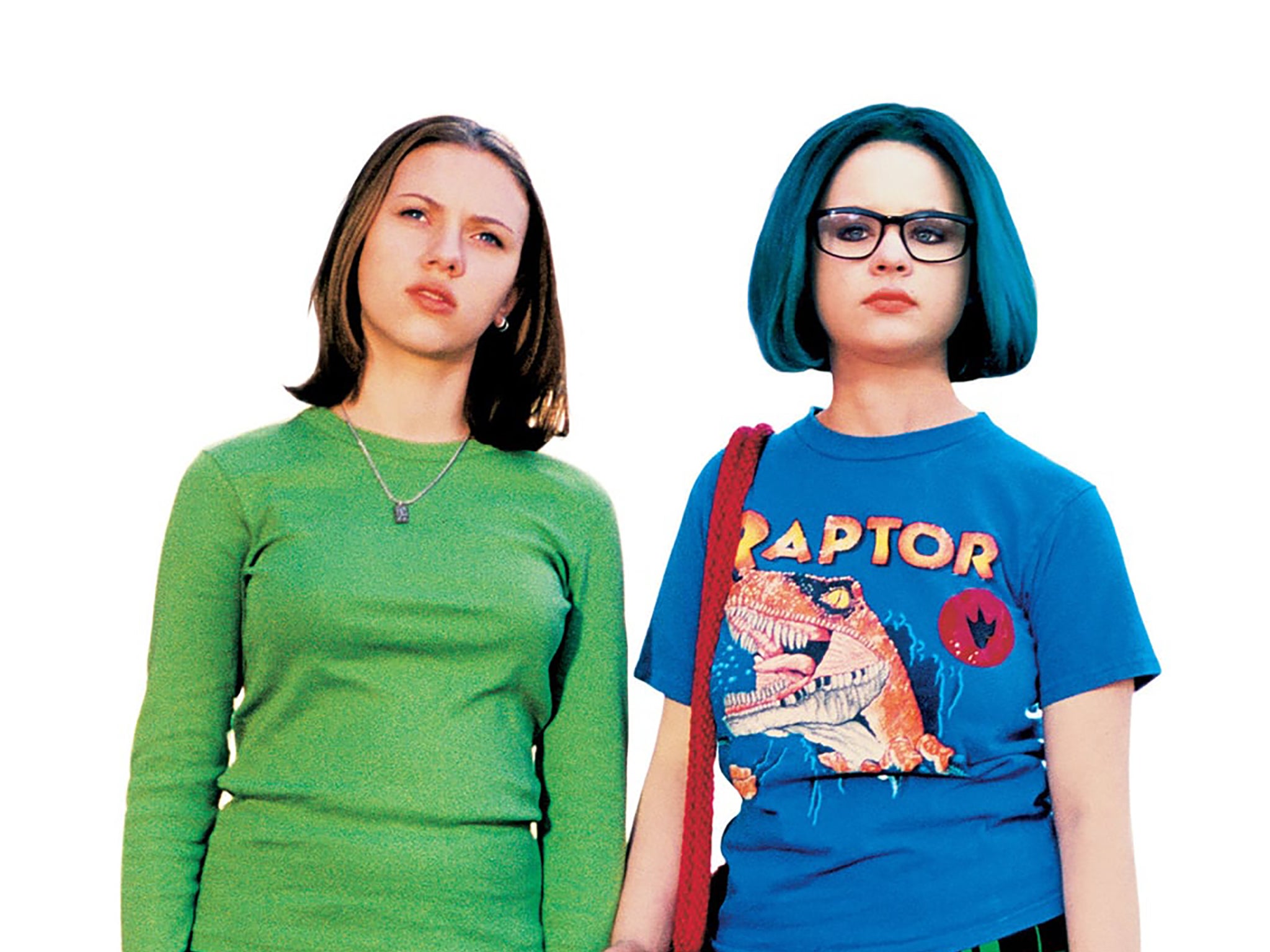

Birch is talking about the first time she saw Ghost World, the 2001 cult classic in which she starred as sardonic school leaver Enid Coleslaw. Her character took deadpan aim at the peppy and pretentious as she wandered, lost, around the cultural wasteland of modern America. She was a new kind of screen hero: detached, self-defeating and committed to the caustic one-liner, regardless of the cost. Ghost World, which turns 20 this year, is surely the funniest film of its era – and perhaps the saddest.

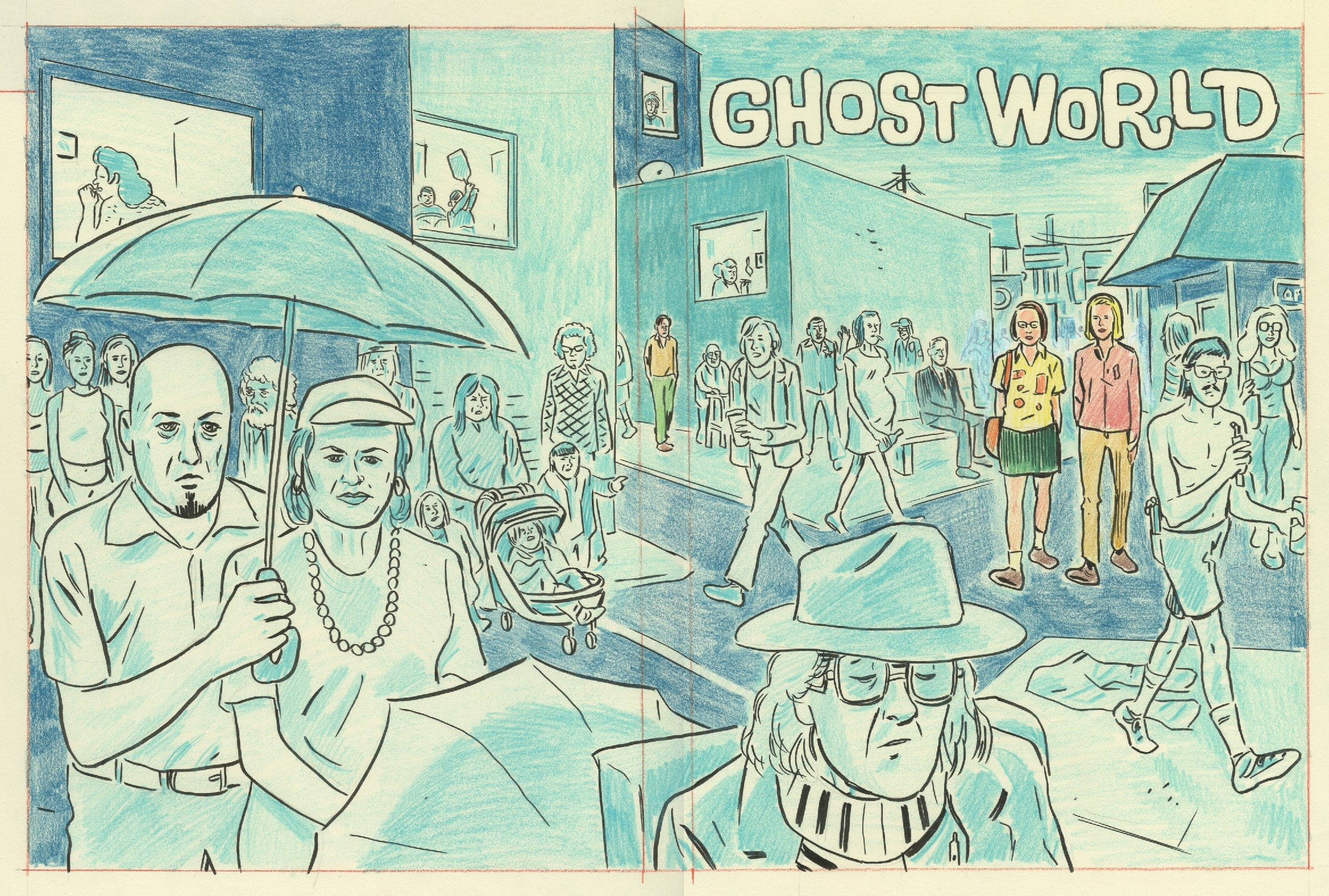

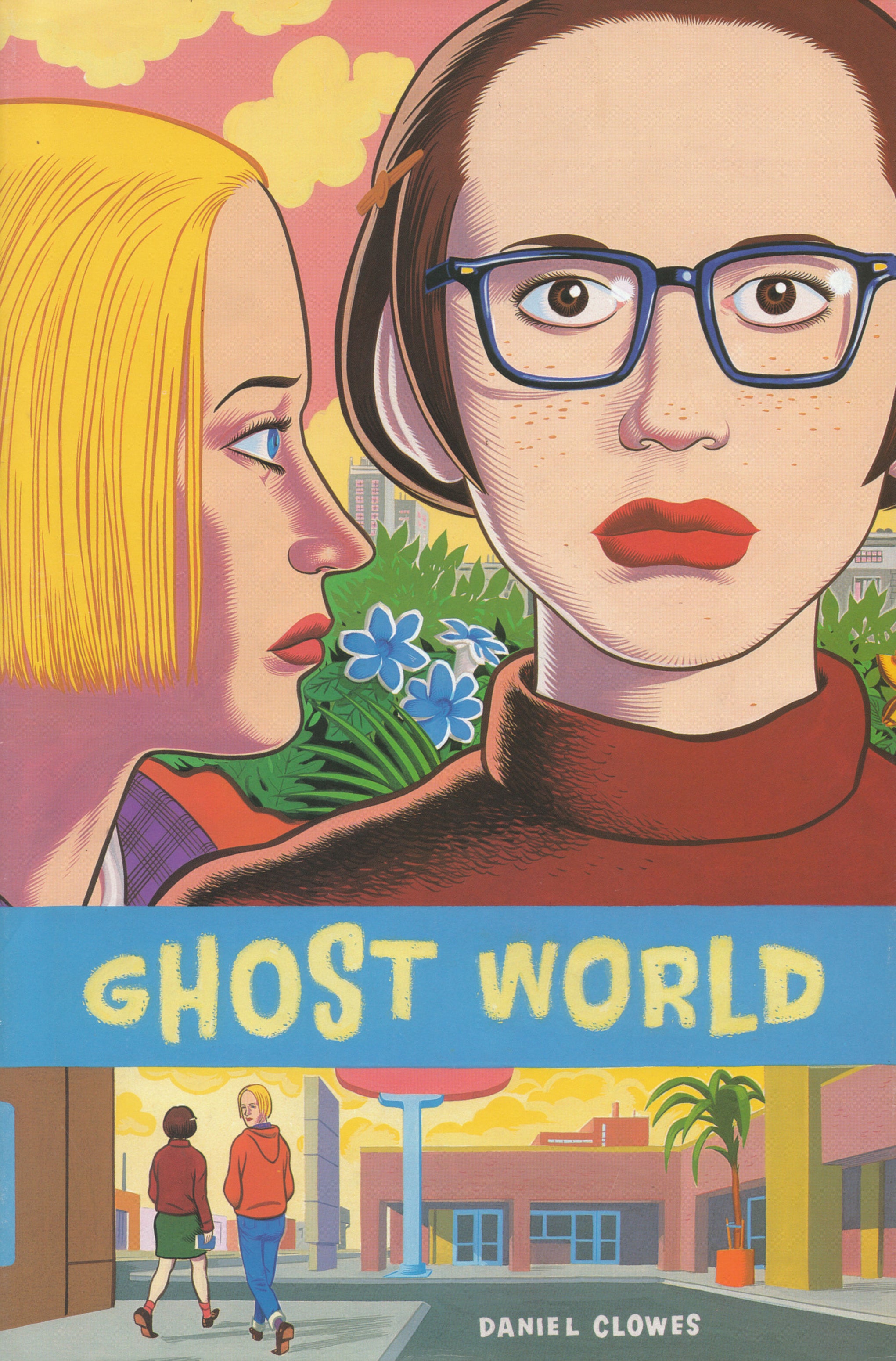

The film was based on a comic by Daniel Clowes. “It never in a million years occurred to me that it could be turned into a movie,” he says. “I was working in the tiny world of small-press comics – not a part of the world that Hollywood even knew about. It happened 100 per cent due to Terry’s interest in working with me.” Terry was Terry Zwigoff, a documentary maker who had created well-received films about country-blues musician Louie Bluie and cartoonist Robert Crumb – two worlds that would bleed into the movie.

“After making Crumb, I started to get scripts sent to me,” says Zwigoff. “I read dozens and dozens of them and thought, ‘These are so contrived and false’ – the ruggedly handsome hero who’s both a tough-guy mountain climber and a nuclear scientist. I could not imagine being involved in such nonsense for a year or two of my life just for a pay cheque. I’m not a writer, but thought, ‘Even I can write better than this slop.’” He wanted to create something rooted in reality. “It’s ironic that I resorted to a comic book to do so, but Dan’s comic wasn’t the typical comic, it was grounded in truth and the characters talked like real people.”

Their collaboration on the screenplay took three years. They expanded the comic’s existential snapshots into the bittersweet story of Enid’s estrangement from her more conventional best friend, Rebecca, and her growing preoccupation with a misanthropic, middle-aged, blues-obsessed dork called Seymour (Steve Buscemi). When Birch, fresh from American Beauty, read the script, she was desperate to play Enid.

What was it about that character? “Basically she had every opinion that I had at the time!” laughs Birch. “At that phase of my life I was just reaching adulthood and not ready for it and not feeling like I ever would be, and so a lot of her lines and the outlook on life were things I really felt, but at that time, I didn’t feel Thora Birch could go around expressing.”

Zwigoff and Clowes wanted her – but to play Rebecca. “They didn’t really see me as an Enid,” says Birch. “But I loved the part so much that I was like, ‘I’m gonna go to lunch with these guys, I’m gonna cut my hair, I’m gonna dye it, and put on these fake glasses and show ’em.’ And it worked.”

It may have worked too well. Though Birch had “a blast” during filming, the line between herself and Enid grew increasingly blurred. “I was in love with the character beforehand but through the process of shooting the film, and the relationships I was developing, that kind of fuelled me – or maybe tricked me – into going for it with abandon. So that… I think it became a bit of a rabbit hole. I had gone so far into Enid that I really was only Enid for a while, maybe for around a year and a half after filming. It took me a long time to re-find my own identity, separate from her. To the degree that it even affected some of my friendships and my relationships.”

There must have been something seductive about negotiating the world as Enid? “Yeah, it’s her lack of filter,” says Birch. “If she wants to tell a redneck hick to go die, then she’s gonna do it. She calls out something that she thinks is lame. She says what she feels. And there is something liberating and freeing about that but it also can cause a lot of damage.”

For teenagers offered a diet of witless frat films, seeing Enid on screen was certainly liberating. “In an era of American Pie and all these teen comedies, this was an antidote to all that,” says Birch. Enid’s worldview is typified by the early scene in which she sways mockingly to the soporific stylings of a dance band, before declaring their performance “so bad it’s gone past good and back to bad again”. Her only moments of release come through music: dancing to Mohammed Rafi, dyeing her hair to the Buzzcocks, and listening to the country blues of Skip James on repeat. But anything that fails to impress, she demolishes with irony or torpedoes with scorn. That goes for every other area of her life too. She is drawn to Seymour because “he’s the exact opposite of everything I really hate”.

People saw themselves in Birch’s character. “There are so many people that have been Enid,” says Illeana Douglas, who played her art teacher. “There are always people who are outside society.” Pop culture writer Hayley Campbell has been immersed in the world of comic books since she was a child. Growing up in Australia, she also felt drawn to Enid. “It’s quite a thing to watch it as a teenage girl, because she’s at a point of frustration where I was,” she explains. “She’s yearning for something different and doesn’t know what, but feels increasingly pressured to find it. And in her frustration she’s even losing the one friend she thought also got that idea.”

Beneath the film’s barrage of mordant gags, that melancholy undertow can get missed. “The whole story arc is how, in some sad way, she can’t even keep a best friend,” says Birch. “Enid is repressing a lot of hurt and anger about a lot of things: growing up without a mum; having a listless father figure who doesn’t really know how to deal with an adolescent young woman. Those are things she never discusses, not even with Rebecca. With the delivery, it was pretty clear-cut – just deadpan your way through it – but underneath that there are all these conflicting emotions. Which is specific to her, but also universal for someone going through that transitional phase of life.”

Ghost World was a springboard for the 15-year-old Scarlett Johansson, cast as Enid’s best friend, Rebecca. Their friendship is no less affecting for being seen only once it has peaked. That past closeness is rendered in small details: a look of fond chastisement on Johansson’s face as Birch toys with a prey, or her passing reference to Enid’s “little old lady phase”. Rebecca’s defining moment is to react with delight to an ironing board that folds out from a cupboard – a sign that she has crossed the Rubicon to a bourgeois life – but she is no villain, just someone finding her place in the world. Like so much of the film, Johansson’s performance is a tightrope walk, and she never stumbles. Many fans find themselves relating first to Enid, then to Rebecca, and finally to Seymour.

Ghost World has moments of overpowering sadness: Birch curled up on her bed, sobbing uncontrollably; her wounded expression in the art studio when she exposes her soul and has it trampled upon. And her devastating climactic speech to Buscemi, which has no conclusions, only pain: “I know I’m a total disappointment to everyone … and there is just no way to explain how I feel.”

More cryptically, there is also the film’s ending. “Many interpreted it to mean Enid died by suicide,” says Zwigoff. “I personally thought of the ending as more positive: that she’s moving on with her life, that she had faith in herself.” Birch’s reading is far bleaker. “Honestly, it’s a sad film, to me,” she says. “I have a very dark view of where that story is leading, unfortunately.”

Those contrasting viewpoints underline Ghost World’s complexity; everyone takes something different from it. For Douglas, it is principally about nonconformity. “In the end, even Seymour conforms,” she says. “When Enid goes in and he’s wearing the blue jeans that his new girlfriend purchased for him, it is this abandoning of everything they’ve made fun of.” Others see it as a film about boredom, or about being unwilling or unable to grow up, while some respond to the characters’ nostalgia for a time they haven’t lived through. Zwigoff had intended partly to critique consumerism: “I wanted to set the story against a background of the sweeping, bland, contrived monoculture of which mindless consumerism is, of course, a part.”

All of those readings are possible because Zwigoff refuses to spoonfeed his audience or file down his characters’ complexities. “One big thing with Terry is he does not worry about whether a character is likeable or not,” says Douglas. “He trusts the audience that that’s our decision.” Not everyone was won over. Though reviews were overwhelmingly positive, with Roger Ebert writing that he wanted to “hug this movie”, veteran critic Andrew Sarris described Enid as “smug, complacent, cruel, deceitful, thoughtless, malicious and disloyal. Worst of all, she’s rarely funny and never charming.”

The critics’ other bugbear, since magnified with the increasing propensity to view films through a moral lens, was the age-gap relationship, and particularly its consummation. Campbell has little patience with that analysis. “To call Seymour and Enid’s friendship ‘problematic’ is to be reductive and unimaginative about who or what teenage girls might find interesting,” she says.

The film’s influence was seismic. It was one of two screenplays Diablo Cody bought copies of before writing Juno, and its DNA can be seen in everything from HBO’s Euphoria to The Last Black Man in San Francisco, the debut feature for which Joe Talbot won Best Director at Sundance. “Thora created someone that made me feel less alone in the world,” says Talbot. In his movie’s most celebrated scene, Birch semi-reprises her Ghost World role. “I like to imagine her character in our movie is as if Enid never got off the bus, and it took her to San Francisco, and she became a tech person and hates what her life has become,” he says.

Seen today, Ghost World remains utterly fresh, and blisteringly funny. Each person I speak to can point instantly to a favourite moment – or several. Zwigoff’s choices include Buscemi’s explosion of rage when a family crosses too slowly in front of his car (“Have some more kids, why don’t you!”), while Clowes is fond of the trailer he wrote for the fake film The Flower That Drank the Moon, brilliantly spearing arthouse pomposity. Birch picks the scenes between Enid and her father’s girlfriend: “Her dealing with Teri Garr is just so brutal and so awful – but I love it.” Campbell often finds herself reflecting on Seymour’s immortal words: “‘I don’t want to meet someone who shares my interests. I hate my interests.’ That to me is one of the finest lines ever written.”

Beyond those lasting virtues, Ghost World may have a special resonance right now. It is, after all, a film about loneliness. “Loneliness does something to you,” says Campbell. “Loneliness and being alone in your own head. And I think this past year has taught that to many people.” Birch agrees, though she says the movie’s jaundiced outlook will always attract like-minded souls. “Introspection is really gripping a lot of people. So I think that comes into play for somebody watching Ghost World now – we’re all kind of forced to be closed off from others. But also: discontentment is not going out of fashion, you know?”

Twenty years on, Enid endures. As our interview comes to a close, I ask Birch to tell me something about her relationship with Ghost World that nobody knows. She pauses for a moment. “Once in a great while, I’ll still scribble in a weird place, like on a film set, or even… I’ve defaced some walls I shouldn’t have. If I’m struck with the moment, I’ll still say ‘Enid was here.’ I’ll just scribble it somewhere. I don’t know why.”

‘Ghost World’is available on Criterion Blu-ray from the US. The soundtrack has been released on vinyl by Cinema Paradiso Recordings

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks