Daniel Gordon’s new feature documentary, George Best: All By Myself: 'Best’s is a story of addiction'

Footballer Best is heard throughout the documentary, telling his own story as if from beyond the grave

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It’s a poignant but pathetic image: a mother is in the car, taking her new baby for a check-up on a wet and miserable night. She sees a man walking down the middle of the road. “This poor man is all hunched over, soaking wet and I think oh my God, that poor homeless tramp and then I realise…it is my husband, drunk as a skunk, walking down the road, soaking wet.”

The woman talking is Angie Best and the man she is describing is George Best, the football genius who has become a stumbling wreck. It’s a scene from the beginning of Daniel Gordon’s new feature documentary, George Best: All By Myself (a world premiere at the London Film Festival this week).

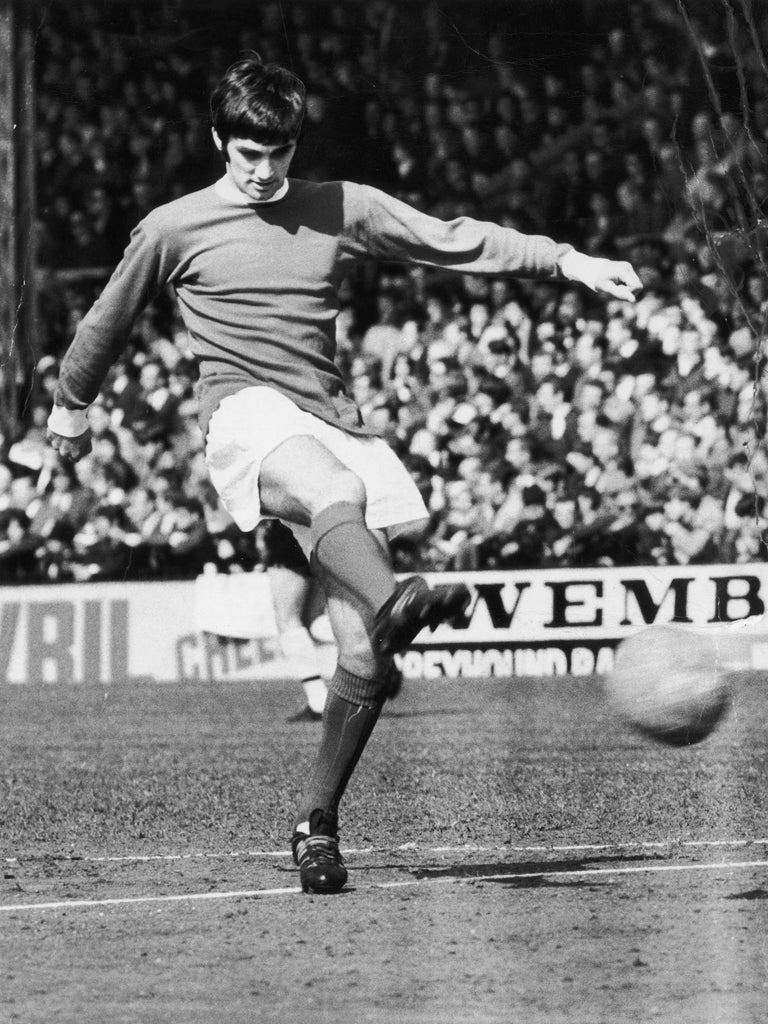

It is now just over a decade since Best died. His story has been told many times before. It is a modern-day rake’s progress. Best was the shy kid from Belfast who came to Manchester United as a teenager and went on to help the club win league titles and a European Cup. The manager Matt Busby regarded him as a surrogate son, a replacement for the so-called “Busby Babes” killed in the Munich disaster of 1958. But then came Best’s slide: the ignominious departure from Man Utd when he was only 27, the alcoholism and the broken marriages.

Director Daniel Gordon is too young to have seen George Best play in his prime but grew up in Manchester and was exposed to the “Best legend” from an early age. He also witnessed Best during his long decline. In making his film, he was determined to “take a fresh approach to a story we all think we know”. He argues that enough time has now passed to allow a more nuanced view of Best than the one that portrays him simply as the “good guy who drank too much” and had demons.

For Gordon, Best’s is a story of “addiction”. As a kid and young man, Best was addicted to football. “That [football] was what he spent every waking hour doing and trying to be the best at”. Everyone who played with him in the early years testified to how well he trained. Then, in the mid 1960s, came the money and the fame – the years when he was dubbed the “fifth Beatle” – and he was a “little addicted” to that too. Then came the women and the booze, the most destructive of his addictions.

“One of the things that was a strong feature of this was not that it was going to be a football story but that it was going to be a human story and for that you need women to tell the story, people who knew him most intimately.”

The film has an impressive array of interviewees: Best’s old teammates like Paddy Crerand; his great friend from the early Manchester years Mike Summerbee; girlfriends and wives, journalists, agents, fans and the son of Best’s landlady in Chorlton. There are some notable absentees, his son Calum Best (reportedly making his own documentary) and Sir Bobby Charlton and Denis Law (both in poor health) among them. Several other prominent footballers, Brian Kidd, Alex Stepney, Willy Morgan and Sammy Mcllroy, were interviewed but didn’t make it into the final cut.

“Everybody always says that the only person George Best ever hurt was himself. That’s nonsense. He hurt an awful lot of people, especially his son,” Gordon says of the footballer.

One of the paradoxes about the documentary is those who suffered most as a result of Best’s drinking and erratic behaviour still retain enormous affection for him. That is true of the three women foregrounded in the film: Angie Best, Alex Best and Jackie Glass, his girlfriend from the 60s who is now a Buddhist nun living in Edinburgh.

“She is very at ease with herself and with her past and was desperately trying not to moralise,’ Gordon says of Glass. As Glass and others point out in the documentary, Best was strangely subdued after winning the European Cup. For Best, as for Matt Busby, this had been a “Holy Grail”. Glass talks of the deflating feeling of “and now what?” that Best experienced in the wake of his greatest sporting triumph.

Angie, who opened a bar called Bestie’s with George, makes an acute observation about the fans who visited the bar. “If 70,000 men wanted to have on drink with George, they had one drink, George had 70,000.”

Best himself is heard throughout the documentary, narrating his own story as if from beyond the grave. Gordon scoured the archives to track down as many interviews with the footballer as he could. Generally, at least when he wasn’t drunk and disorderly on the Terry Wogan show, Best spoke perceptively about his life and career.

Even at his lowest ebb, Best retained marketability. The tabloids always wanted stories about him. He could be off his head in a gutter or even on his death bed and the agents could still sell a story.

Watching the film now, it is hard not to be reminded of Asif Kapadia’s Amy Winehouse documentary. The director acknowledges the similarity between the films. “If you look at all the headlines George Best generated, he was used and abused, belittled…when I saw Amy and I saw the paparazzi camped outside (her home), all those scenes, the wide shots of the press, you hounding her, it was probably 50 times worse than what George Best faced but George Best was the first one to have faced that.”

Late in his life, Best could often be found drinking in the Phene Arms in Chelsea. He worked for a while as a commentator on Sky Sports. This period is skirted over in the documentary. “It’s not that that was a less interesting period but I think if we had fully explored that period, it would have been one long tale of woe and decline. There weren’t a great deal of highs of any description. I was working at Sky Sports at the time and there were plenty of times he didn’t turn up,” the director says. “The reason he didn’t turn up was that he was still in the Phene Arms and decided not to bother. Everyone just shrugged their shoulder and said, ‘well, that’s George’.”

Ask Gordon whether he admires Best more having made the documentary and the director gives an equivocal reply. “You feel admiration for what he did at the beginning; you feel horror at how it turned out and you feel disdain at decisions he took; you feel empathy for what he faced; you feel a bit of anger at friends who weren’t able to intervene and help. Then you realise that George made all those decisions for himself and that no one really forced him to be anything other than the person he became.”

Gordon didn’t want to make an overly depressing film. There’s little danger of that when there are so many clips of him playing football so brilliantly. One clip stands out more than any other. It is not from his Manchester Utd years but from his long stay in America. He was playing for the San Jose Earthquakes and their opponents had just scored a goal that was clearly offside. Best was furious. He was overweight, and not especially fit but his anger galvanised him. Somehow, he summoned up the old genius and for a few moments he became the player he once was. From the kick-off, in his rage, he took the ball and embarked on an astonishing slalom-like run, dribbling past the entire opposing team before eventually finding the space to shoot and score. “That’s the greatest soccer goal I’ve ever seen,” the American TV commentator said at the time. Those few seconds serve to remind us why, 11 years after his death, everyone is still as fascinated as ever by George Best.

George Best: All By Myself is a world premiere at the London Film Festival on Fri 14 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments