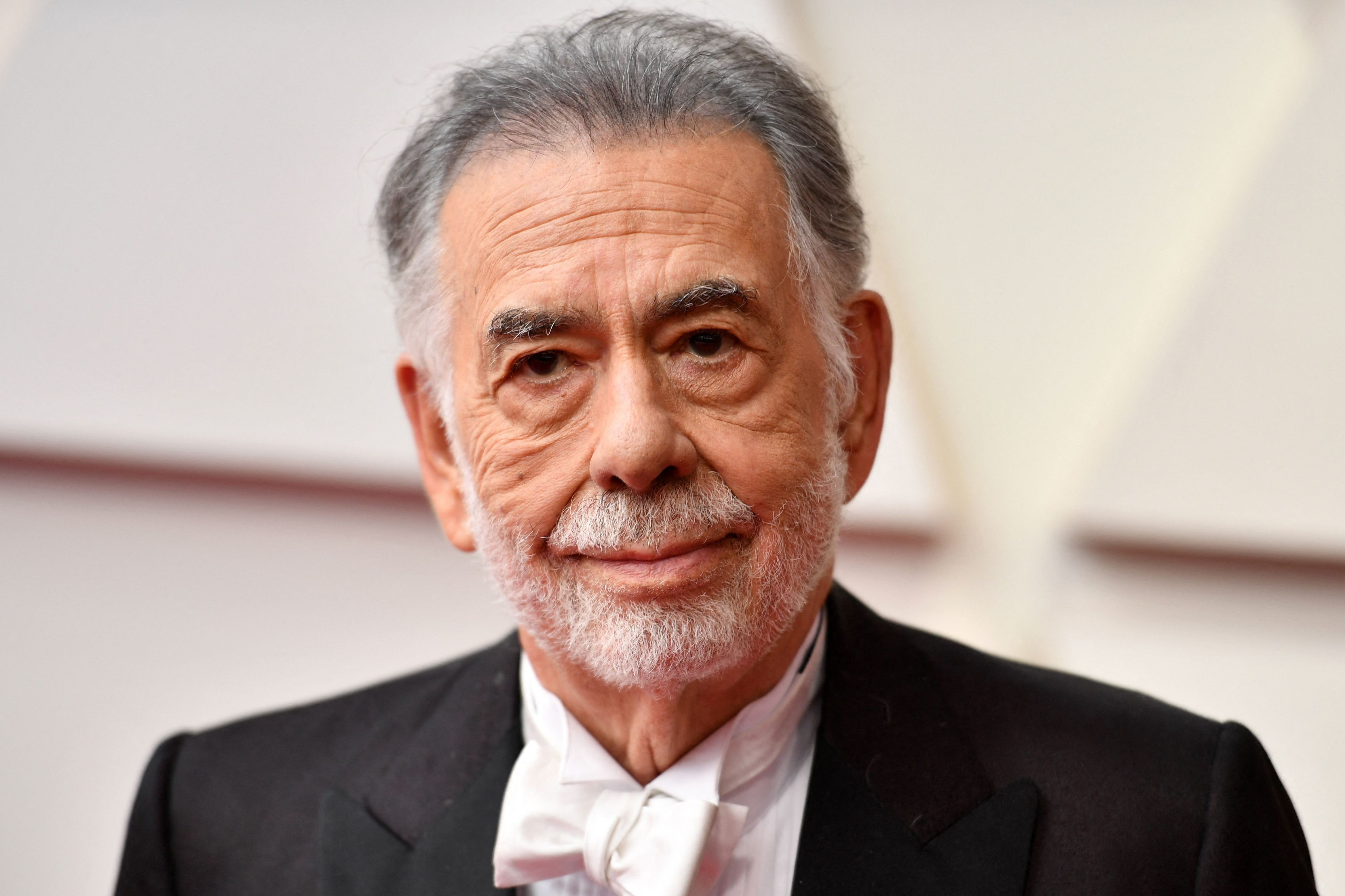

Hollywood can’t help being suspicious about Francis Ford Coppola – Megalopolis isn’t going to change that

Despite 50 years in the business and multiple Oscar wins, the veteran director still struggled to get funding for his latest film, which will make its debut at Cannes. Here, Geoffrey Macnab looks at why the man who brought us ‘Apocalypse Now’ and ‘The Godfather’ will always be an outsider

The gloating was obvious. “Just no way to position this movie,” read the headline in The Hollywood Reporter. Quoting one of many nonplussed film executives who had just seen Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis, the article asked if the $120m (£96m) passion project would be unreleasable in the US. After an industry screening in Los Angeles in late March, the film (premiering in competition in Cannes next week) was already being dismissed as yet another of its legendary director’s folies de grandeur. None of the big US studio distributors knew what to do with it – and none (as yet) has acquired it.

“It’s a movie that makes you think. It’s not only entertainment,” one spectator said after the screening – words that seemed to fill the studios with dread. Thinking doesn’t sell popcorn. The director, who auctioned off part of his lucrative wine business to finance the film, was reportedly asking for a sizeable chunk of the profits from the release – something the studios simply weren’t prepared to countenance.

Did they want to see him fall on his face? That was the impression given by some of the more snide post-screening remarks. It was as if the Hollywood executives were looking for payback for all those past occasions when Coppola had criticised their way of doing business, or when he had taken their money and produced a box-office turkey, such as the romantic musical One from the Heart (1981) or his car designer biopic Tucker: The Man and His Dream (1988).

Even when he was in his pomp in the 1970s – making a run of classics that included the first two Godfathers, The Conversation, and his gargantuan Vietnam war epic Apocalypse Now – Hollywood studios were intensely wary of the mercurial Italian-American auteur. Fifty years on, they remain as suspicious as ever. The 85-year-old may have won multiple Oscars, but he is arguably as much an outsider now as when he was making his first exploitation pics for B-movie maestro Roger Corman in the early 1960s.

Megalopolis is a Roman-style epic set in contemporary America. Adam Driver plays Cesar Catilina, a brilliant and idealistic artist, scientist and designer. He has a vision of a future where ritual, celebration and art are sacred – and he seemingly has the ability to stop time. (In the teaser footage released last week, Driver is seen at the top of a sleek golden skyscraper, looking down at the streets far below, his smart shoes pressed against the ledge. Just when it looks as if he’s about to topple to his death, he yells, “Time stop!”)

Pitted against Cesar is mayor Franklyn Cicero (Giancarlo Esposito), who represents corporate greed and wants to fill New Rome with malls and casinos, places where “pay cheques are lost and kids go hungry”.

Cicero’s beautiful daughter Julia (Nathalie Emmanuel from Game of Thrones) is the love interest who comes between the two men – so this is another Coppola saga about love and family as well as power and politics. It’s territory he’s been exploring since the days of the Corleones.

Coppola was asked about Megalopolis at a press conference during the Marrakech festival in 2002. By then he had already spent 20 years developing the project. He had recently shot several hours of what he described as second-unit footage in New York, and had been reflecting heavily on the need for reconciliation with the Islamic world after 9/11. There was no sense, though, that the film was anywhere near coming together, and he was adamant that he wasn’t going to finance it with studio support.

“It’s not the movie business, it’s the money business,” Coppola said then, fulminating against the Hollywood studios. “I will never ask them for money. That’s all they have. That’s their power.”

At the time, these seemed like the words of someone who already knew he’d never get backing anyway. Few expected him to complete Megalopolis – and certainly not on a blockbuster scale. If he was going to make the film at all, the likelihood was that it would be shot as an experimental art movie, like Orson Welles’ posthumously completed The Other Side of the Wind (2018) or one of those late Nicholas Ray films made with students, or in the vein of his own modestly financed indie dramas, such as the grungey arthouse pictures Youth Without Youth (2007), filmed in Romania, or Tetro (2009), made in Argentina.

Two decades on, Coppola has defied the sceptics and completed the new movie exactly as he intended, remaining in control of every aspect of the production. That in itself is an expression of Spartacus-like defiance and independence after all those years when he was forced to work as a director for hire in Hollywood. Throughout his career, the writer-director’s financial problems and bankruptcies have enabled the studios to keep him on a tight leash and assign him projects he would never have chosen himself. (The 1986 fantasy romance Peggy Sue Got Married is a fun movie, but not one Coppola would ever have undertaken unless he was deep in the red.)

It would nonetheless be a big mistake to regard him as another of those maverick visionaries like Welles or DW Griffith, spat out by the Hollywood system. His relationship with his Hollywood paymasters was attritional from the start. He had always dreamed of setting up his own alternative studio system – one that favoured the artists over the executives.

“He likes to work with young talent, giving them a chance,” an LA-based producer who has worked on all of Coppola’s recent movies, from Youth Without Youth to the experimental 40-camera student project Distant Vision and Megalopolis itself, tells The Independent. (She asks not to be named because she doesn’t want to steal any of Coppola’s limelight.) “He likes to have full control to preserve the vision that he has; he sees the film in a certain way. But the other aspect of him is that he is very, very collaborative. He lets his main collaborators surprise him and bring their own originality to the project.”

Movie lore is full of stories about Coppola tantrums. During his early fights to cast Apocalypse Now (1979), he grew so angry at being turned down by stars like Al Pacino and Steve McQueen, he famously threw his Godfather Oscars through his dining-room window. The obituaries of his wife Eleanor (who died last month) quoted her very poignant diary description of the incident. “The children pick up the pieces in the backyard. Four of the five are broken...”

Then there was the time during the crisis-stricken shooting of Apocalypse Now when he was so stressed out and fed up that he climbed up onto a lighting platform, lay down, curled up like a foetus and went to sleep in the middle of a rainstorm as the cast and crew waited for instruction 30ft below him.

Coppola is often caricatured as a megalomaniac with a volcanic temper, but that’s not at all how the young producer I speak to describes him. “He is always learning, always reading and educating [himself], never stops, always has a book, always talks with young people that are on set,” they say. “His mind is very creative, but also leans into the scientific world ... he’s very erudite, for sure.”

Coppola’s legacy extends beyond his own filmmaking career: perhaps his greatest accomplishment has been founding production company American Zoetrope in 1969 – and then somehow keeping it alive, in one version or another, ever since. Jean-Luc Godard, Paul Schrader, Norman Mailer, Kenneth Branagh, Tim Burton, Hal Hartley, and Robert De Niro are among the directors to have released films under Zoetrope’s umbrella.

“The whole idea of our company was that everybody – all the filmmakers – could do whatever they wanted,” he explained, summing up the collective, freewheeling Zoetrope spirit. The enterprise, originally housed in a warehouse in San Francisco with Coppola as owner and George Lucas as vice-president, worked along lines diametrically opposed to those of the Hollywood studios – and yet depended on those studios for support. That was always the problem.

As has been exhaustively chronicled, Coppola accepted his career-changing assignment on The Godfather (1972) only under duress, after the inevitable financial difficulties began at Zoetrope. At the time, he owed Warner Bros a reported $300,000. He may have been broke, but he didn’t like the Mario Puzo mafia novel, and initially turned the job down. Star Wars’ George Lucas told him it was an offer he couldn’t afford to refuse. Coppola eventually followed the advice, but insisted on trying to make the film on his own terms.

“Coppola had set an incredibly high standard of excellence,” biographer Michael Schumacher wrote, characterising a painstaking approach that often drove the director’s backers wild. He was a tinkerer and a perfectionist, who wasn’t ever going to rush or compromise regardless of the pressure placed on him.

The director’s antagonism towards Hollywood intensified yet further after his runaway success with the first two Godfather movies. He had earned Paramount a fortune, and yet neither it nor any of the other major US studios would finance his Vietnam war movie Apocalypse Now. The budget was eventually cobbled together through pre-sales to European companies and a big advance from US distributor United Artists.

It’s not hard to find the autobiographical elements in Coppola’s films, from Apocalypse Now to Megalopolis. Early on in the former is a famous scene with Harrison Ford’s Colonel Lucas briefing Captain Willard (Martin Sheen) about the man he is being sent to terminate. Colonel Walter E Kurtz (Marlon Brando) is a senior US officer with impeccable credentials who has gone “rogue” in Cambodia with a private army of soldiers who worship him.

There are traces of Coppola in both Kurtz and Willard. When you hear the US officers describing Kurtz as an outstanding officer whose “ideas and method became unsound”, they could just as well be Hollywood executives describing Coppola. Willard, meanwhile, encountering death and madness on his mission up river, has clear similarities to the filmmaker, taking on ever crazier and more destructive assignments. As for Megalopolis, Cesar’s struggles against the mayor mirror Coppola’s own tussles with all those mercenary studio bosses.

The irony is that Coppola has always depended on those bosses. He can’t get his films distributed properly without them. They’re deeply distrustful of him, but, at the backs of their minds, they still remember that The Godfather grossed an astonishing $250m on a budget of $6m.

“It’s a complex, demanding, highly intelligent piece of work, coming into a marketplace that does not always embrace those qualities,” trade paper Variety wrote in 1979, warning that Apocalypse Now was likely to be a very tough proposition at the box office. Forty-five years later, the same doom-laden forecasts are being made about Megalopolis. Apocalypse Now ended up making $105m on a $31.5m budget, and is heralded as one of the greatest films ever made. Who’s to say that Coppola won’t pull the same trick again?

‘Megalopolis’ has its world premiere at the Cannes Film Festival on Thursday 16 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks