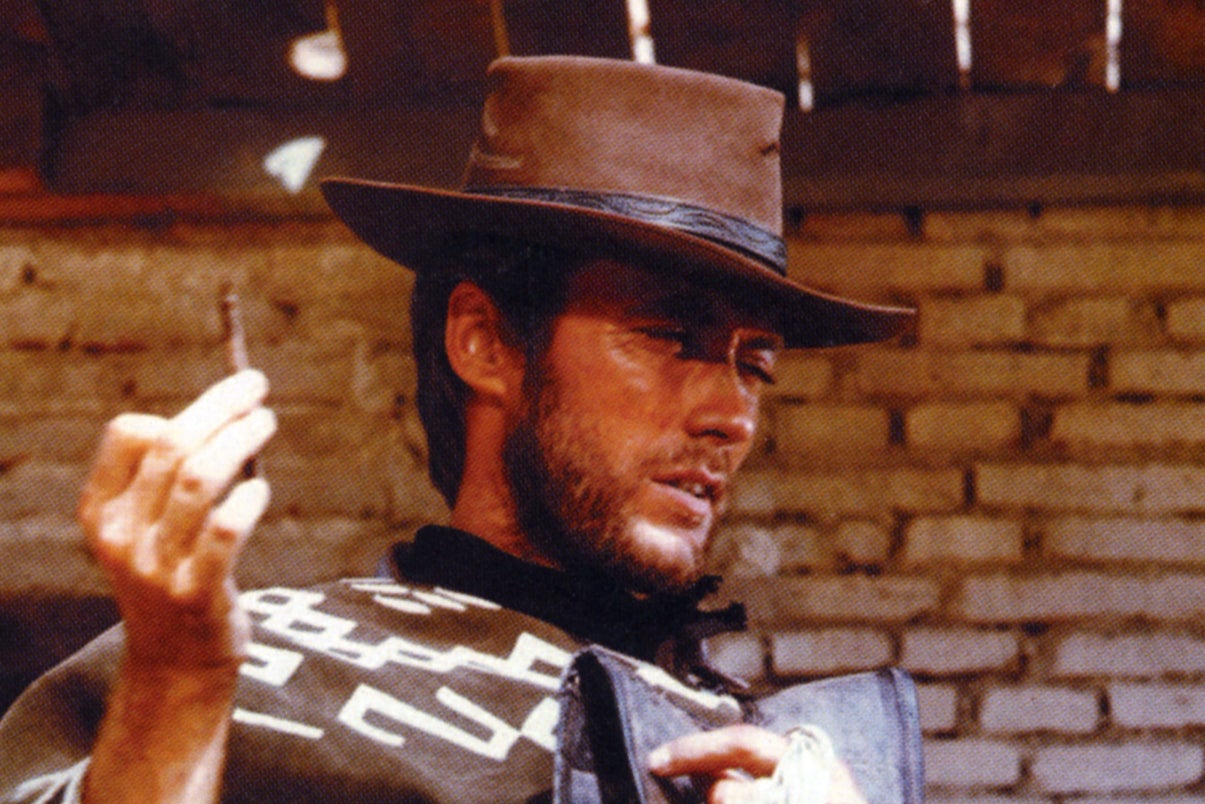

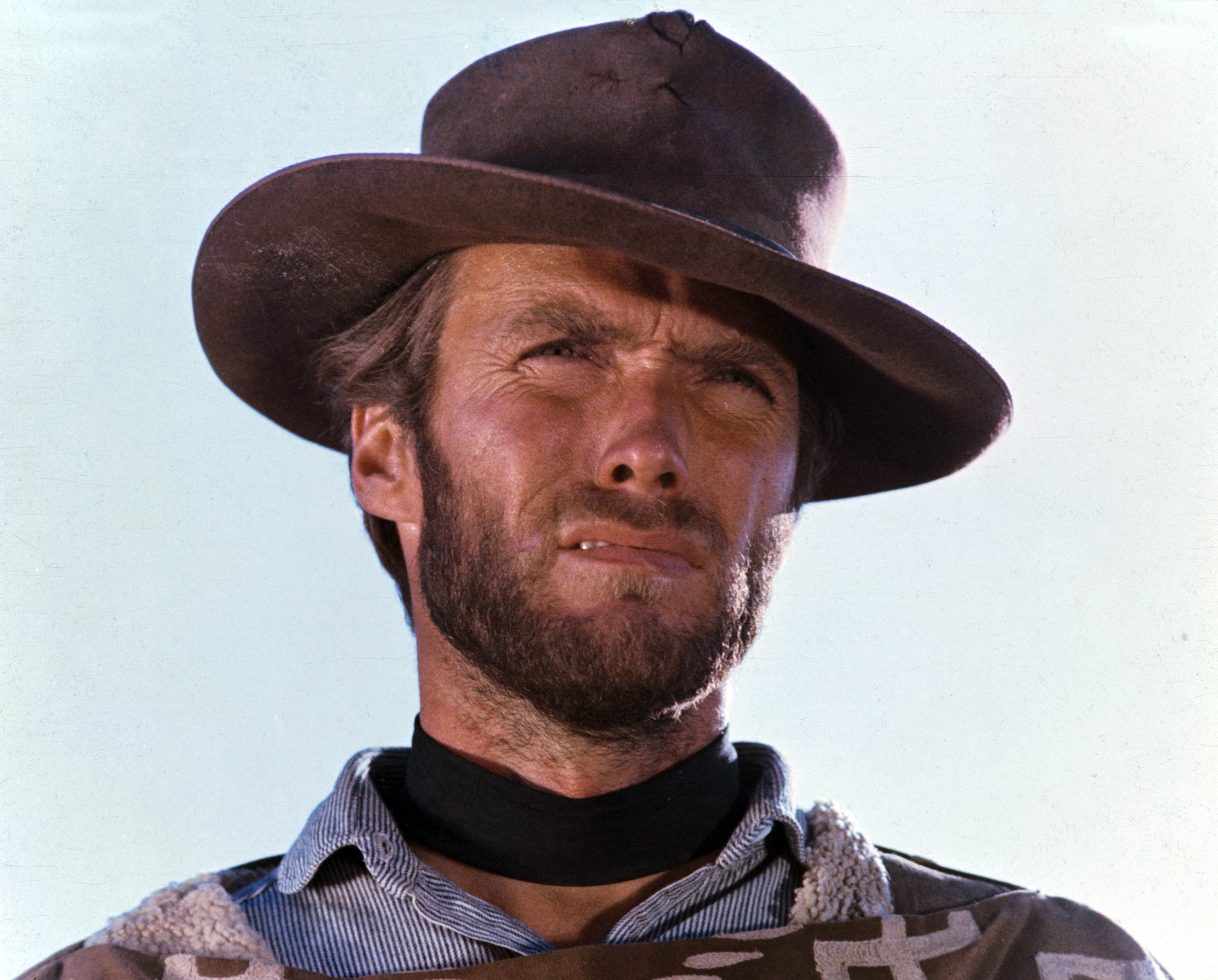

How Clint Eastwood and Sergio Leone’s fractious chemistry made A Fistful of Dollars into a classic

Geoffrey Macnab explores how the films revolving around Eastwood’s ‘man with no name’ became one of cinema’s unlikeliest success stories

Would you believe me if I told you that one of the most important films ever made was a low-budget Italian movie from 1964, directed by a then-unknown filmmaker called Bob Robertson? Well, it’s true.

Of course, you probably know Robertson by his real name: Sergio Leone. The Italian filmmaker chose the pseudonym partly as a tribute to his father (who had acted under the name Roberto Roberti) and partly because he felt it might improve the international prospects for A Fistful of Dollars (1964).

By all accounts, Leone and his leading actor Clint Eastwood couldn’t understand each other. The former didn’t speak English and the latter didn’t speak Italian. Leone had wanted Henry Fonda but couldn’t afford him. Eastwood, then co-starring as “the dumb sidekick” Rowdy Yates in US TV show Rawhide, wasn’t even second choice – but he came cheap.

Eastwood later claimed that he took the role in A Fistful of Dollars because he thought the Italian director had “a good sense of humour” and because he had nothing to lose. If the film flopped, he could go back to Rawhide. American TV audiences wouldn’t even realise that he had been away. It was a summer holiday job and he kept his expectations low.

“I had questions, normal questions, like, ‘Who is Sergio Leone?’ It wasn’t like Fellini was offering to do it,” the actor later told journalist Peter Biskind.

The perplexion was mutual: after being shown an episode of Rawhide, Leone described Eastwood as “this man, with a vacant look on his face in an unwatchable film about cows”, according to biographer Christopher Frayling. Unable to afford anything better, he nonetheless hired the 34-year-old TV cowboy, paying $15,000 for his services.

One of the paradoxes about the collaboration between Leone and Eastwood is that they worked so well together without being able to communicate. Both were yet to establish their reputations. They were similar ages. Leone was born in 1929, Eastwood in 1930. “I spun off Sergio, and Sergio spun off me,” Eastwood said in a 1984 interview.

As time passed, there were disputes over who did what. It rankled with Eastwood that Leone never gave him any credit and it pained Leone that Eastwood’s career so quickly outstripped his own.

Leone famously quipped that his lead actor had only two expressions (“with or without hat”), as if he was little more than a puppet. Eastwood responded that he was the one who had pared down the original screenplay, throwing out all the unnecessary dialogue and character exposition – thereby making the ”no name guy” all the more mysterious and charismatic.

Often, when movie stars say they were responsible for key creative decisions in their movies, they’re simply blustering. In Eastwood’s case, we have to take his claims seriously. After all, he made his own directorial debut in 1971 with Play Misty for Me and has gone on to become one of the most revered and prolific directors of his generation.

My favourite movie of all time is The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Why? Because it is the greatest achievement in the history of cinema

From the start, A Fistful of Dollars seemed like an exercise in grand cinematic larceny. Leone “stole” his storyline (about an outsider turning two rival families against each other) directly from Akira Kurosawa’s 1961 samurai movie, Yojimbo, starring Toshiro Mifune. He was also attempting, in a shamelessly opportunistic way, to capitalise on the newfound popularity of spaghetti westerns and on a short-lived early 1960s fad for German “sauerkraut” westerns based on Karl May novels. (These, Leone told Frayling, were “like very bad television… but at least showed that the West still has some magic in it”.)

Kurosawa demanded reparations from Leone. Frayling reports that the Japanese maestro sent the young Italian pretender a letter saying “I have just had the chance to see your film. It is a very fine film but it is my film.” Leone, though, said that his curiosity had been “stirred” by an article in the Italian press claiming that Kurosawa had himself taken elements from Dashiell Hammett’s classic crime novel, Red Harvest, about a detective trying to clean up a crime-riddled town. Others noted Kurosawa’s debt to Hammett’s 1929 novel, The Glass Key (also a strong influence on the Coen brothers’ 1990 gangster film Miller’s Crossing).

When they were sued, another unlikely justification Leone and his producers advanced for borrowing so freely from Kurosawa was that the Japanese director himself had based his plot on an 18th-century play by the Italian writer Carlo Goldoni.

Sixty years on, the lines between genius and plagiarism have long become hopelessly blurred. What can safely be asserted is that Kurosawa’s classic contained elements of hardboiled American crime fiction, while Leone’s spaghetti western had a distinctly samurai flavour. Whether it’s theft or cross-cultural fertilisation, both films benefitted from the exchange.

A Fistful of Dollars doesn’t begin in pre-possessing fashion. Its hero, originally to have been called Ray but who achieved screen immortality as “the man with no name”, rides into a dusty Mexican town on the back of a mule. He’s not like the dashing, well-scrubbed gunslingers audiences were used to from Shane or old John Wayne movies. A grizzled, unshaven hobo wearing a poncho, he can’t even afford to buy himself a plate of food in the saloon. The local gunslingers mock and humiliate him. He remains laidback, asking them to apologise to his mule for insulting it. Their refusal gives him the excuse to shoot and kill four of them.

This was the first of the many moments in Leone westerns when the storytelling switches from torpor to frenzy in an instant. “When you build up to an action scene, it’s ‘Pow! Exciting!’ and then it’s back to being very leisurely,” Eastwood said, explaining the unusual tempo of Leone’s movies.

The Leone/Eastwood trilogy was made hot on the stirrups of the first James Bond movies. There are obvious overlaps between the franchises. They boast resilient but fatalistic heroes who take a matter-of-fact approach to killing. They share the same stylised credits and both use musical themes (John Barry’s and Monty Norman’s in Bond, Ennio Morricone’s in the Leone films) in wildly expressionistic fashion. Both also have a cartoonish quality – the Bond movies with their gadgets and the spaghetti westerns with their knockabout violence.

Leone’s films are also frequently compared to opera and Commedia dell’arte. They’re episodic, exaggerated and most of their supporting characters are stock types. The Italian director isn’t interested in psychological realism.

When you watch A Fistful of Dollars again, you realise that the lone cowboy isn’t quite as taciturn as legend has it. At certain moments, for instance when he is shooting the breeze with the saloon owner, he becomes almost garrulous. But it is in those famous widescreen close-ups, when he is shown chewing laconically on his cigar before the next shootout, that he becomes like an old silent movie star. Both Leone and his lead actor realised that faces could be far more eloquent than words.

There were a series of lucky accidents. The film was originally going to be called first Ray the Magnificent and then The Magnificent Stranger but the name was changed to the far more memorable A Fistful of Dollars in post-production. The legal case against Leone, launched by Toho, Kurosawa’s production company, delayed the film’s US release; that meant the film and its two sequels – For a Few Dollars More (1965) and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966) – all ended up being seen by American audiences within the space of a few months in 1967. That couldn’t help but intensify their sudden impact.

Contemporary reviewers were ambivalent about the three movies, praising their “top-notch” action sequences but also sometimes finding them strangely distasteful. “A curious amalgam of the visually striking, the dramatically feeble and the offensively sadistic,” Variety’s reviewer wrote of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, complaining about its “too-muchness”.

Nonetheless, the films had a huge cultural impact. “My favourite movie of all time is The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Why? Because it is the greatest achievement in the history of cinema,” Quentin Tarantino once baldly stated. He was among the most celebrated of the American cinephiles who became cheerleaders for Leone. Martin Scorsese was another of Leone’s fervent admirers (and was behind the 2011 restoration of Leone’s gangster masterpiece Once Upon a Time in America).

As the years passed, Eastwood still wasn’t always polite about Leone (“he’s not very good at directing actors”) but acknowledged in a 1976 interview with Patrick McGilligan “that working on the European scene sort of inspired me to get back into directing”. His career both behind and in front of the camera would have been completely different if it hadn’t been for that summer interlude with Sergio.

Leone borrowed from Hollywood but in turn made American directors look at their own country – and their filmmaking traditions – in a new way. They adopted his mannerisms – that familiar mix of flamboyance, irony and extreme violence. Leone’s work is still quoted endlessly in US pop culture, in everything from The Simpsons to HBO’s Westworld and Robert Rodriguez’s “Mariachi” westerns.

Fittingly, the man once accused of filching from Kurosawa has also influenced a generation of Asian filmmakers. Directors like Takashi Miike (in his 2007 movie Sukiyaki Western Django) and Tsui Hark, director of 1991’s Once Upon a Time in China, have acknowledged their debt to him.

When Francesco Zippel made his recent documentary Sergio Leone: The Italian Who Invented America (now screening on Sky), everyone he approached, from Tarantino to Steven Spielberg, to Robert De Niro, immediately agreed to interviews. “He [Leone] is the Italian filmmaker who is the most contemporary and most influential,” Zippel says.

Celebrating its 60th anniversary in September, A Fistful of Dollars remains an outlier, a film that seemed to come from nowhere. “When it was finished [shooting], I never heard from anyone… I wondered what had happened to that movie,” Eastwood said, of the summer folly he thought had disappeared without a trace. He eventually read that it was a hit in Italy – and a few months later, when it finally arrived in the US, his life and career were transformed. But its legacy goes far beyond just Eastwood: Tarantino and others have hailed this magnificently odd, low-budget western as being “the beginning of modern cinema”. It’s a bold claim – but arguably a true one.

‘A Fistful of Dollars’ is available on Prime Video. ‘Sergio Leone: The Italian Who Invented America’ can be seen on Sky

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments