Legendary documentarian Errol Morris on his explosive John le Carré film: ‘He didn’t want to talk about sex’

Errol Morris, the Oscar-winning filmmaker behind genre-defining docs including ‘The Thin Blue Line’ and ‘The Fog of War’, was granted rare access to the spy novelist shortly before he died in 2020. The resulting film, ‘The Pigeon Tunnel’, is an unflinching portrait of a literary great. But the characteristically curmudgeonly Morris isn’t personally sure about its quality, he tells James Mottram

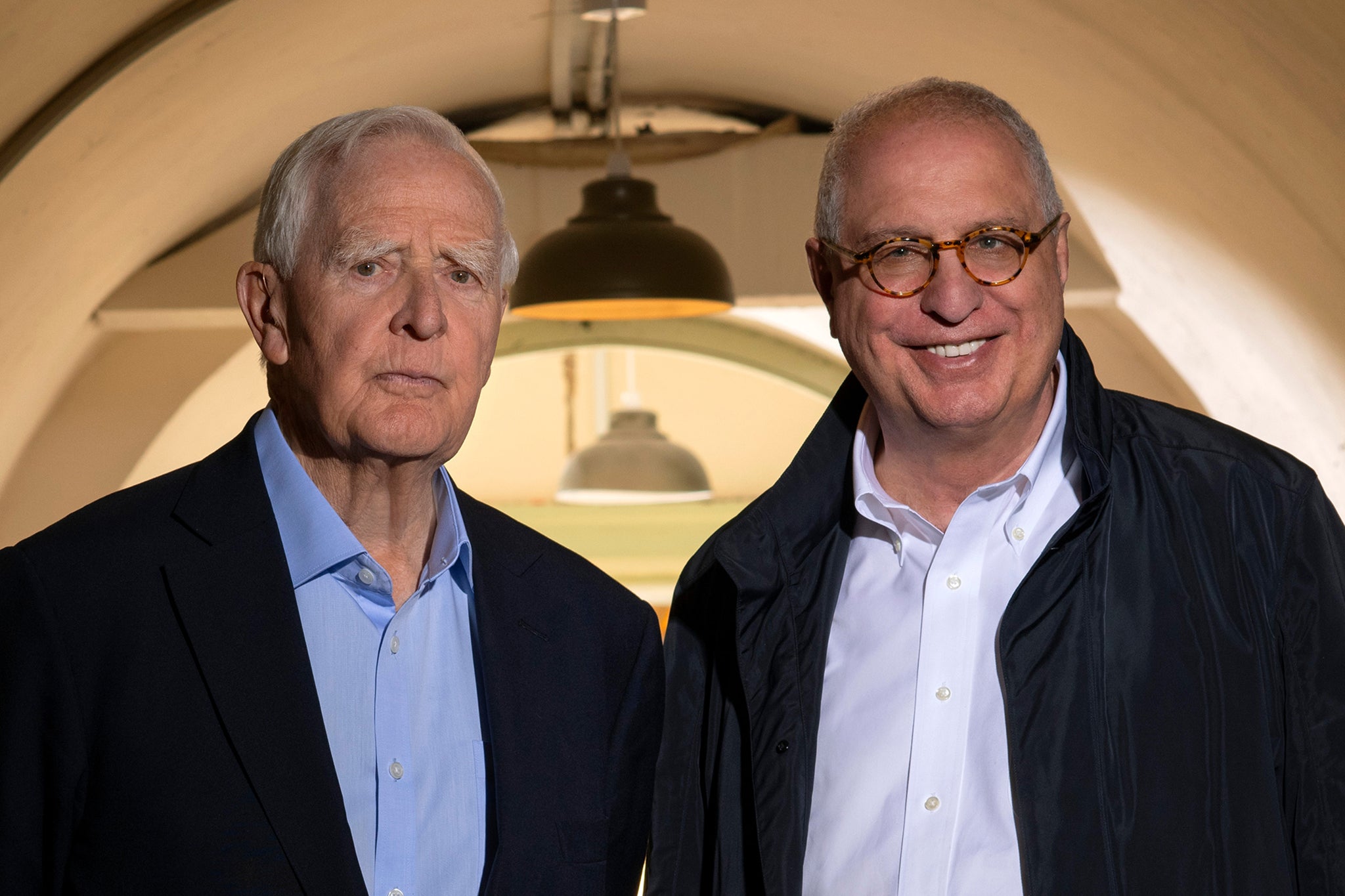

Errol Morris is arguably one of the greatest living documentary filmmakers. The 75-year-old American may also be one of the grumpiest. Films like The Thin Blue Line (1988), about the killing of a Dallas police officer, and his Oscar-winning The Fog of War (2003), about former US secretary of defence Robert McNamara, have changed the way we think about non-fiction films. But when we meet in London to talk about his latest film, The Pigeon Tunnel, an absorbing portrait of John le Carré, author of classic espionage novels A Perfect Spy and The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, he’s ready to shred any enquiries he doesn’t like.

I gently ask why Le Carré, whose real name was David Cornwell, wanted to participate in the film, which delves deeply into his personal relations, especially with his father Ronnie. “I find it a crazy question,” Morris retorts. “As if, somehow, I am myself lodged somewhere in his brain. Do I know exactly why he decided to do this interview? No.” Did he never say? “He does say at some point during the interview that I can ask him any question I choose. And he says he will answer any question that I care to ask. He also says he doesn’t want to talk about his sex life! I have to admit, I wasn’t particularly interested in talking about his sex life.”

The film is sculpted around 2016’s The Pigeon Tunnel, Le Carré’s autobiographical account of his early years and his time in the British intelligence services during the Cold War. “I often compare him to [Heart of Darkness author Joseph] Conrad, because here you have a guy travelling the world, interacting with people, with history,” Morris says, admiringly. “And for me, it’s one of the things that makes him this incredibly fascinating character. Not the fact he was f***ing around. I’m sorry. [For that] you get Masters and Johnson to interview him.”

Morris is alluding to the fact Le Carré, as a young man, left his wife and family and undertook what he once called a “galaxy of inappropriate affairs” – including his sometime research assistant, Sue “Suleika” Dawson, who published her own tell-all account, The Secret Heart, shortly after Le Carré’s death in December 2020 at the age of 89.

“One thing I did not understand fully – at the time that I did the interview in 2019, just pre-Covid – is that he’d been involved in all of these affairs,” says Morris. “And if I’d known all of this, would I have done the interview differently? Probably not. I myself was interested in something completely different: the philosophy of John le Carré, how he sees the world.” Did Morris want this to be the definitive portrait of Le Carré? “No, that would be just stupid,” he replies, bluntly. But perhaps Le Carré did?

“I think from his own perspective, inevitably, he had a sense that he was approaching the end of his life,” says Simon Cornwell, 66, Le Carré’s eldest son. “I don’t think he intended to die,” adds his second-eldest son Stephen, 63. “I think he was interested in his legacy. I think he was self-reflective, increasingly – not in any maudlin way but in really looking at the foundations of his own creativity. And the way it has informed his work.”

The Cornwells are producers on the film, as they have been on various recent successful adaptations of Le Carré’s work, including the Florence Pugh-starrer The Little Drummer Girl and The Night Manager, a BBC-made phenomenon that introduced his work to a whole new generation. But this must be a wholly different experience: a close-up portrait of their father. “I think the journey that the film went on inevitably changed,” says Simon. “It changed for us, it changed for Errol, because our dad died and that did throw a whole new perspective onto it. And it does become incontrovertibly definitive… because it was the last one.”

He had a complicated life, but at the same time, he was the patriarch of a remarkably functional family, even though it has many different bits and wrinkles to it

At one point in the film, Le Carré talks about his childhood and says, “I’ve been on the run ever since.” What did Morris make of that? “He’s a person of course, who has reflected endlessly on his upbringing, on his father in particular,” he says. Ronnie, a “five-star conman” as the author once called him, had been jailed for insurance fraud and was acquainted with the Krays. “The relationship between him and his father Ronnie… complex,” says Morris, with typical understatement. “Ronnie is almost like a Donald Trump-type character.”

Le Carré once wrote that he worried he came from the same “mad genes-bank” as his father. “Ronnie massively informed the father he became, in that he clearly did not want to be that person,” says Stephen. His brother nods, adding: “He worked very, very hard not to be his own father. I mean, he lived to write, but interwoven with that was a real sense of, I think, responsibility towards family and a desire to get it right… and give us all the things that he didn’t have when he was growing up. Oddly, I think he succeeded in that. Yes, he split up from Mum early on… he had a complicated life, but at the same time, he was the patriarch of a remarkably functional family, even though it has many different bits and wrinkles to it.”

One of the things that makes The Pigeon Tunnel so engaging is how warily Le Carré first regards Morris. “Who are you?” he asks of the filmmaker. He is ready for an interrogation, and explains he’s done his due diligence by looking into Morris’s canon. “To say that he would express interest in my work – yes, flattering, I’m pleased. Totally surprising? No, not really. It’s in keeping with who he is,” says Morris.

“I think he’d always admired Errol,” notes Simon. “I mean, I think he thought The Fog of War was a great movie. And I remember talking about it with him years before the question of him being interviewed by Errol ever came up.”

It was during this Fog of War period that Morris switched towards creating one-on-one portraits: controversial subjects like McNamara, two-time US secretary of defence Donald Rumsfeld (2013’s The Unknown Known), Trump strategist Steve Bannon (2018’s American Dharma) and now Le Carré. Yet what’s fascinating is how Morris often confesses his own vulnerabilities in these films, how he feels he’s failed to get under their skin. “Maybe I feel less confident than most filmmakers,” he says. Why? Does he doubt his process? “Inevitably, there’s stuff that you wish you’d asked, but you didn’t. Stuff that did not turn out as well as you might have hoped. I mean, that’s part of the deal. I hope, for example, that I am not an extreme disappointment to you.”

He’s not. But meeting Morris, a former private detective no less, is akin to walking into a bear trap. In a recent fiery, revealing Q&A with the New York Times, Morris went on the offensive with interviewer David Marchese, turning the tables and attempting to ask him questions. Why did he do that? “When I’ve tried to ask interviewers questions about what they’re doing, in my experience… we can try this with you and see what happens… they freak out! ‘How dare you? I’m supposed to be asking you questions, not the other way around. F*** you! Don’t you dare! Don’t you even think for a second of doing that. That’s wrong!’ I think it freaks them out.”

In the same article, Morris admitted he wanted to get back to the spirit of his earlier movies, like his 1978 debut Gates of Heaven, about a pet cemetery. What did he mean by that? “Not doing the same damn old thing every time,” he says. Does he feel his recent films have become formulaic, to some degree? “I worry about it. I guess one should always worry about it. I believe, in the first films that I made, there was a kind of strange, anarchic element. Maybe because I didn’t know what I was doing, maybe because I did know what I was doing. Hard to say.”

In the wake of Gates of Heaven, Morris pioneered the use of dramatic recreations in documentaries – casting actors to flesh out the story, a technique he still uses, even in The Pigeon Tunnel. “I got into trouble when I made The Thin Blue Line years ago… many people said, ‘Well, how dare you? How dare you do that? That’s wrong.’” Why? Because you’re reinventing scenes you didn’t witness? “That has to be part of it. But it’s a naive idea to think that film is giving you truth anyway. Godard said that film was truth at 24 frames a second. I have a different version. Film is lies at 24 frames a second.”

In fact, Morris thinks you shouldn’t even call his films documentaries. “I don’t like being called a documentarian,” he says. “I’m not even sure that I like documentary. I do like making films. I think the films that I have been making are closer to drama than they are to documentary. Or, if you like, they’re a hybrid of the two. There’s this odd mixture of drama – I like to think extremely well-shot drama, well-acted, well-choreographed – and this element of the spontaneous that we associate with documentary. I look at it as a kind of different art form.”

‘The Pigeon Tunnel’ is in select cinemas and streams on Apple TV+ from 20 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments