On the Waterfront at 70: An undeniable masterpiece – but should we forgive its director Elia Kazan?

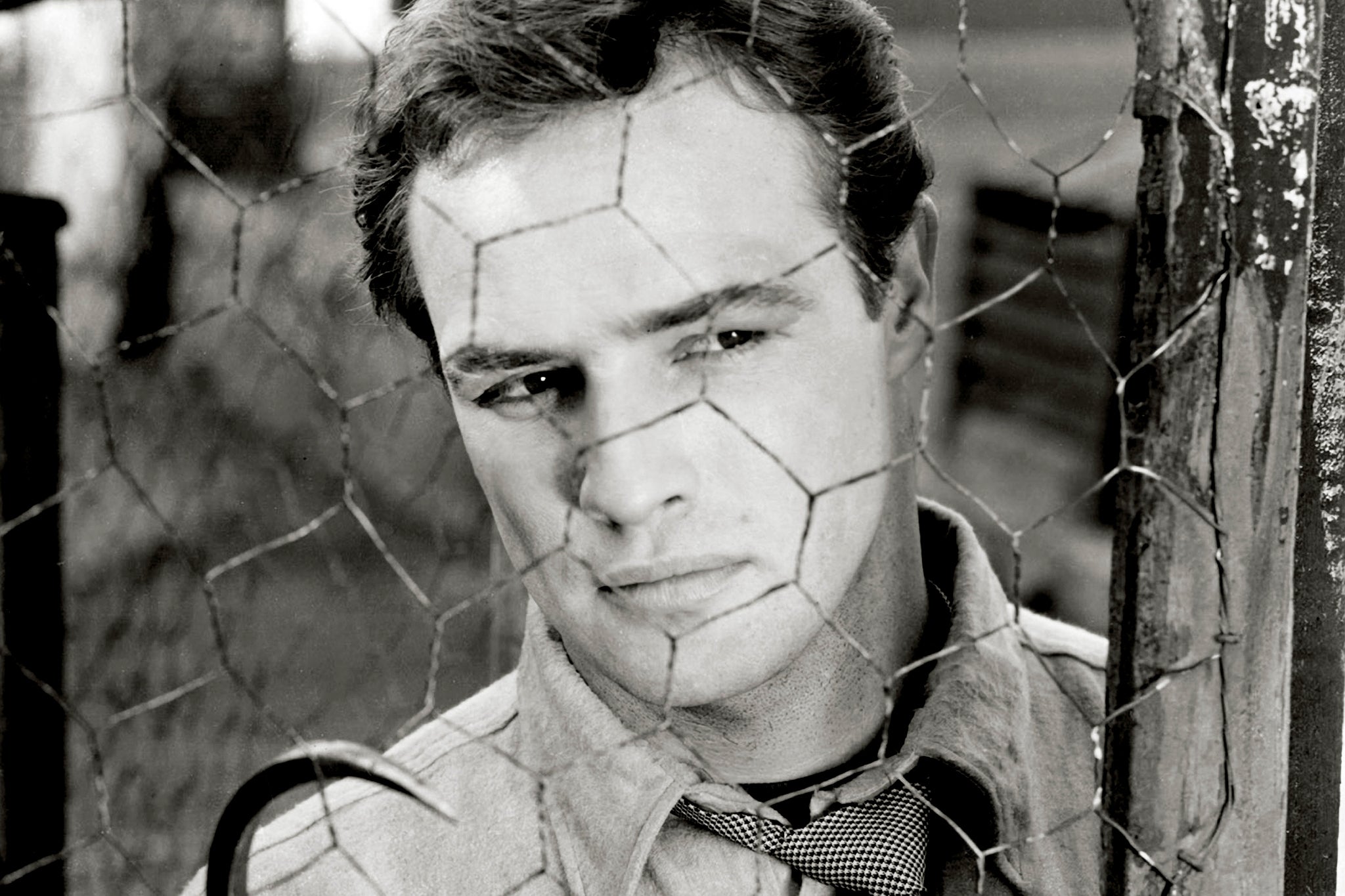

The classic Marlon Brando film swept the Oscars in 1955 and is about to be re-released in cinemas to mark its 70th anniversary. But its politics and the actions of its director – who ‘named names’ during the anti-communist witch hunts of the Fifties, and whose legacy remains marred ever since – have made it one of Hollywood’s most divisive movies. Where should we stand on it today, asks Geoffrey Macnab

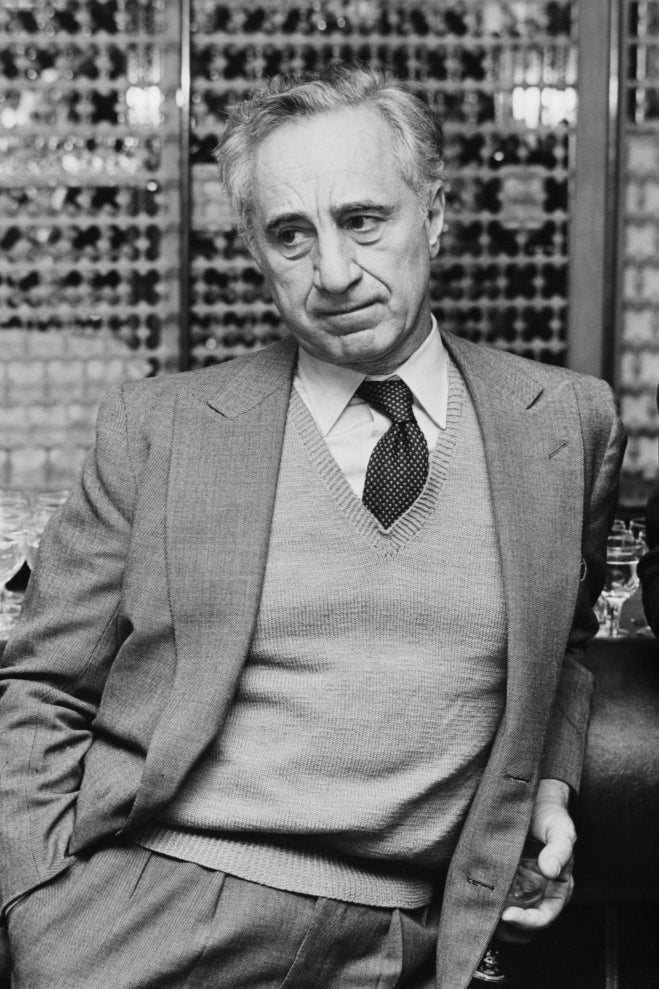

Snitch” and “stool pigeon for racist American imperialism” read the placards outside the 1999 Academy Awards, in which filmmaker Elia Kazan – then 89 years old – was due to receive an honorary Oscar. When time came in the night for the award, presenters Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro heaped praise on the man behind On the Waterfront, East of Eden and A Streetcar Named Desire, calling him a “master” and an “angry romantic”, who explored the “suppressed raging discontents of our civilisation”. But when Kazan appeared, large swathes of the audience remained conspicuously seated, their hands by their laps and refusing to applaud.

On the Waterfront is being re-released next month in a 4K restoration to mark its 70th anniversary, but the din over Kazan’s perceived treachery still hasn’t died down. Should he be forgiven for naming eight close friends and former colleagues to the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) during the anti-communist witch hunts of the early 1950s? Or should he and his films continue to be interrogated?

“Elia Kazan is a traitor,” Orson Welles said in 1982. “He is the man who sold to McCarthy all of his companions at a time when he could continue to work in New York at [a] high salary. And having sold all of his people to [Senator Joseph] McCarthy, he then made a film called On the Waterfront, which was a celebration of the informer and therefore no question which uses him as an example can be answered by me.”

Kazan was astonishingly gifted. Does it matter that the director, who joined the Communist Party in 1934 and stayed until 1936, betrayed his colleagues? In On the Waterfront, Kazan turns that question on its head. He makes such a betrayal seem like a heroic gesture.

“What’s ratting to them is telling the truth for you,” boxer and longshoreman Terry Molloy (Marlon Brando) is told by his priest (Karl Malden), who encourages him to testify against the mobsters who control the docks. Terry is the film’s martyr figure, enduring physical intimidation and violence before doing the “right” thing.

The film was written by Budd Schulberg, who also named names. Co-starring as the mobster union boss Johnny Friendly was Lee J Cobb, the original Willy Loman in Kazan’s stage production of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman. And, yes, Cobb named names too.

Understandably, Park Circus, the distributor re-releasing On the Waterfront, isn’t paying much attention to the 70-year-old controversy over Kazan’s “betrayal” of his former colleagues. Its marketing is focusing firmly on the eight Oscars that the film won, and on the fact that Brando would have celebrated his 100th birthday this year. Another selling point is the musical score by Leonard Bernstein, recently the subject of Bradley Cooper’s well-received biopic Maestro. The publicity conspicuously fails to mention the bitter disputes that still rumble around the movie.

Since 1954, many apologist and revisionist historians have sought to distance On the Waterfront from the controversy over its director’s testimony to HUAC. Kazan himself continued to defend his own actions. He repeatedly pointed out that the names he gave were already known to the Committee – he wasn’t putting anyone in fresh trouble, he reasoned. Researchers have also tried to establish that Schulberg was hard at work on his screenplay before he was summoned to the committee investigating communist influence in Hollywood. This meant that his work wasn’t written, as The New York Times reported, “to justify naming names”.

Nonetheless, Kazan’s comments about his actions were often deeply ambivalent and hinted at the shame he clearly felt. “Anybody who informs on other people is doing something disturbing and even disgusting,” he told author Jeff Young. But he then argued that his actions had to be judged from the perspective of the early 1950s, with “the Korean War still going on”, and Russia a threatening, “monolithic” power. With wriggling logic, the director simultaneously described his testimony as not “a big deal”, but also an act of huge defiance and courage. “Communists were in a lot of organisations – unseen, unrecognised, unbeknownst to anybody. I thought, ‘if I don’t talk, nobody will know about it’.”

Arthur Miller, whose play The Crucible was inspired by the McCarthy witch hunts and who himself refused to name names to HUAC, revered Kazan, but their relationship foundered because of his testimony. He later wrote in his autobiography Timebends that it was an “undeniable fact” that the director “might have sacrificed me had it been necessary”. He asked: “Who or what was now safer because this man in his human weakness had been forced to humiliate himself? What truth had been enhanced by all this anguish?”

Seventy years on, a strong argument can be made that it is precisely the remorse and bad faith attempts by Kazan and Schulberg to justify their actions that make On the Waterfront such a compelling movie. This is a film steeped in guilt and regret, and that is what gives it its layers of pathos and moral complexity. If it hadn’t been for the red scare, it wouldn’t have been the same picture.

Kazan loved America but was always aware of his outsider status. He was an immigrant who had come to the country at age four from Anatolia. He was both desperate to fit in and fiercely critical of the inequality and hypocrisy in American public life. The very first scene in On the Waterfront echoes those feelings of betrayal. Terry lures his dockworker colleague Joey, who has agreed to testify to the crime commission, onto a rooftop. Once there, Joey is thrown to his death by Johnny Friendly’s goons. Terry is immediately stricken with anguish. He had thought Friendly’s thugs were just going to “lean on” Joey, not “knock him off”.

Then there is the film’s most famous scene, in which Terry bemoans to his brother Charlie (Rod Steiger) about the ruins of his boxing career and the mediocrity of his life. “You was my brother Charlie, you should have looked after me,” Terry says. “I could have had class. I could have been a contender. I could have been… somebody, instead of a bum which is what I am.”

Kazan portrays a world in which everyone crumbles. Brothers are turned against brothers, fathers against sons. Terry won’t tell Joey’s sister Edie (Eva Marie Saint) about his role in Joey’s death. Others are too intimidated to talk to the cops about the corrupt union bosses.

The brilliance of Brando’s performance lies in its haunted quality and its strange mix of sensitivity and machismo. Like his director, he knows he has done something wrong. His face expresses his extreme regret. There is even something masochistic about him, a sense he half-relishes when Johnny beats him up so badly at the end of the movie that he can’t get up. It’s what he deserves.

All these years later, Kazan’s actions seem as shabby and incomprehensible as ever. He claimed to hate Senator McCarthy, who spearheaded the campaign against alleged communist and Soviet influence in the US – yet ended up on exactly the same side as this supposed nemesis. Schulberg’s screenplay ties itself in knots, portraying the priest as a hero and the authorities as decent and fair-minded. Such a perspective would have been anathema to him a few years before.

The director and his writer had clearly moved a long way from their communist beliefs of the 1930s. Nonetheless, they hadn’t abandoned those beliefs altogether. On the Waterfront is nothing if not contradictory. It shows aspects of working-class American life that you simply don’t find in more polished Hollywood dramas made from a position of smug moral certainty.

“Shut up about that conscience! That’s all I’ve been hearing,” Terry yells at Edie as his guilt threatens to overwhelm him. Brando plays his role with such searing, emotional intensity that most audiences quickly forget the contorted politics of the film he’s in. For many, On the Waterfront is a masterpiece – whatever they feel about the director who made it.

‘On the Waterfront’ is re-released in cinemas on 5 April

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments