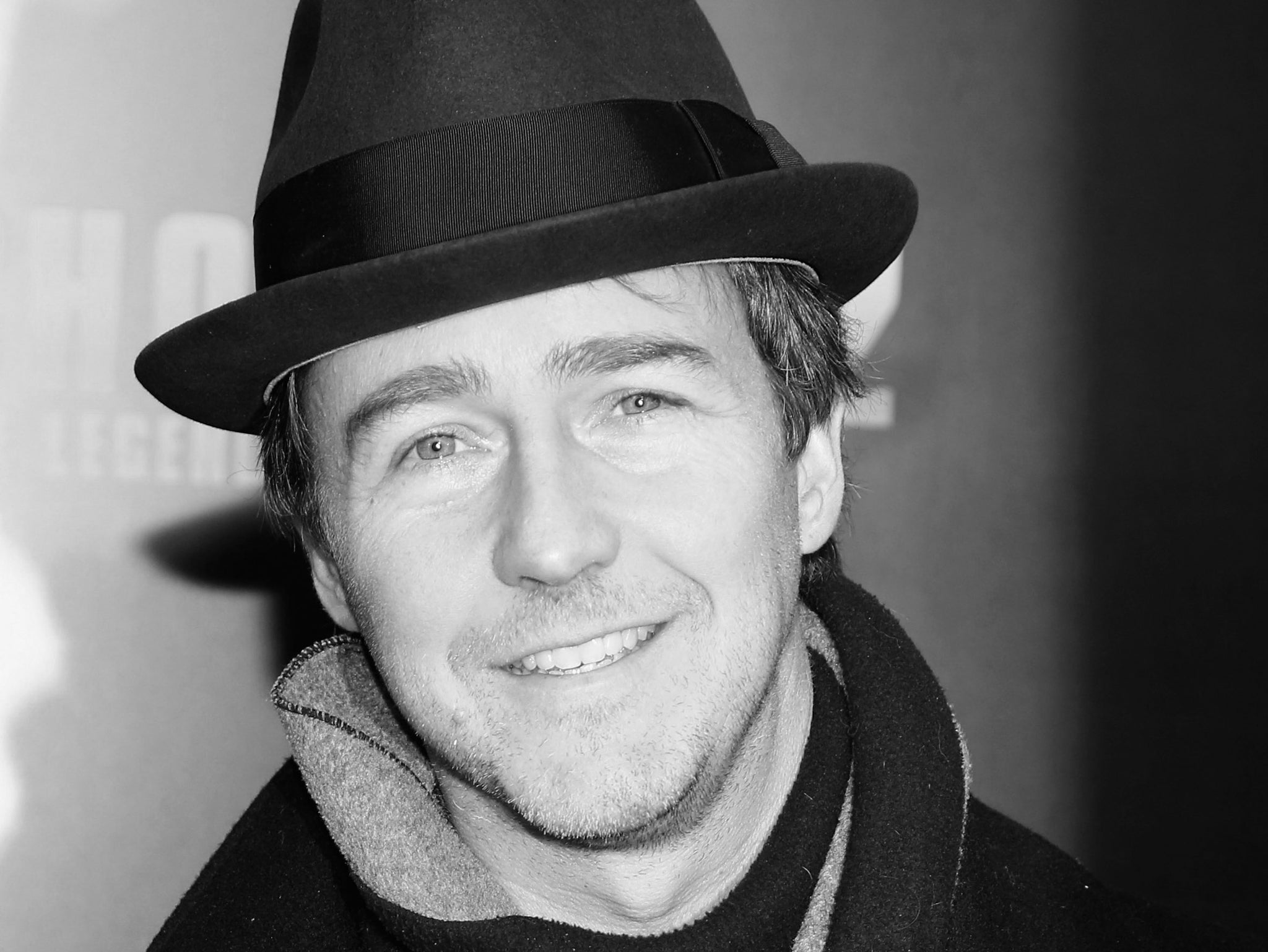

Edward Norton interview: Fight Club actor talks Bruce Springsteen relationship advice, American History X, socialism and President Obama

Edward Norton may be uncomfortable using the 'S' word but his history of political activism tells its own story

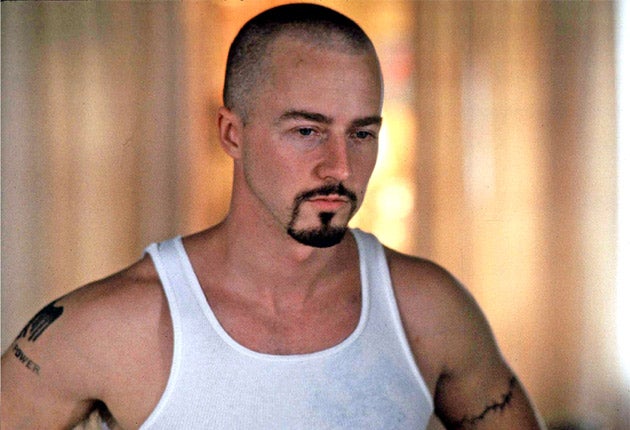

A few years ago Edward Norton was sitting on a stoop in New York listening to Bruce Springsteen. Actually listening to Bruce Springsteen: the singer was sitting on the step next to Norton giving the actor some relationship advice. At the time Norton had already established himself as one of the world’s leading actors, following up his Oscar-nominated debut in Primal Fear with turns in American History X and The People vs. Larry Flynt, and one of the all-time great performances in Fight Club.

“He’s very wise,” Norton says of “The Boss”. “He’s a very down-to-Earth guy. He’s a very self-analytical and self-demanding person who wants to be a real human being and work on what it means to be a human being and what it means to be a husband and father.”

The advice Springsteen offered seems straightforward. “He said relationships are hard work and you have to keep redefining them.” Clearly these words have struck a chord, because the description that Norton gives of Springsteen could today be applied to the actor himself: Norton brought his Canadian film producer wife, Shauna Robertson, and their son to the Locarno Film Festival, where the actor picked up a career achievement award. He’s also more than fulfilling his quota of being human, having helped set up Crowdrise, a not-for-profit crowd-funding website for those raising funds for charitable causes, as well as being on the board of an affordable-housing scheme, and is supporting several environmental causes.

His career is also riding high. Last year he was elected the chairman of the board of trustees for Signature Theatre, the not-for-profit arts organisation that gave Norton his first high-profile Off-Broadway role in Edward Albee’s Fragments, in 1993. It was then that the Boston-born actor, who grew up in Columbia, Maryland, an area founded by his grandfather James Rouse, moved to New York, where he still calls home.

On screen, the past year has seen two excellent turns. He reunited with Wes Anderson to play the nemesis Henckels in the highly stylised drama The Grand Budapest Hotel. Then he almost stole the show from Michael Keaton in Birdman, playing a committed thespian with preconceived notions of what is good acting.

Both Keaton and Norton seemed to be playing versions of themselves in Birdman, or at the least the media perception of them. Like his character, Norton has a reputation for being a great actor who can sometimes be difficult to manage. He famously fought with director Tony Kaye over the cut of American History X. Norton won. Norton seemed to be laughing at himself by playing a famous actor prone to arguments with his collaborators. I mention American History X in this context and Norton lets out a small laugh before explaining: “Yeah, I think that, one of the things for lots of people is that it can be transitory, or at least it evolves. You start to think at the beginning, when you are younger, you think that it’s more empowering to be able to communicate on a public forum and I think that as you get older, you realise that what you are trying to do is protect the authenticity of what you are doing, rather than trying to project things onto the world.”

Norton is placatory about his past battles, and seems partially to blame himself for some of his public spats: “If you’re lucky, you get more at ease with the idea that you are just a small part of the world and maybe the ambition for any number of things, starts to settle a bit.”

In 1996 Norton became an overnight sensation. In Primal Fear he played an altar boy, with a stutter and a split personality, accused of murdering an archbishop. He was equally convincing as innocent child and brutal sociopath. In Fight Club he also showed several sides of a split personality. Throughout his career, whether he has been working with Woody Allen, Spike Lee, or Wes Anderson, Norton has fluctuated between emotional extremes. After Primal Fear, Norton had a three-picture deal with Paramount, but didn’t like the parts offered. He had the choice of the best roles in Hollywood. Eventually he cut a deal to star in the remake of The Italian Job to fulfil his contractual requirement, and then refused to promote the film. Similarly, he withdrew from media duties for The Incredible Hulk, having made rewrites to the script. The performances came with a certain dark side.

Now he has mellowed, but he is also more choosy about the choice of roles. I ask if it’s because he heeded Springsteen’s advice and now has a family.

“Yeah, I think that,” he responds. “I would say personal life, family life, you want to balance things, but it’s an interesting paradox because being an actor is not a thing you do all the time. If you are lucky enough, it leaves a lot of time to engage in other things and if you are engaged in other things that are really compelling or interesting or challenging to a different part of your brain or your personality, paradoxically it raises the threshold that a piece of work has to meet to interest you and pull you away from all that other stuff. Whereas before my ambition was almost unilaterally focused on acting, it’s not any more.”

Political activism is another string to his bow. He’s a supporter of President Obama and, in 2012 with Foxcatcher director Bennett Miller, produced pro-Obama documentary We Hold These Truths at the behest of his friend, campaign manager Davie Axelrod. This followed on from his producing the 2009 short film By the People: The Election of Barack Obama. He believes that the Obama presidency is improving with time: “Between Iran, Cuba and last week’s climate announcement on carbon emissions, significant things are happening. What Obama is doing at the end of his presidency is proof of how well he plays the long game. He realises you can’t do everything at once, you have to sequence things like a chess master.”

Social action runs in Norton’s veins. His grandfather, the philanthropist James Rouse, championed social housing. His own website Crowdwise has charity as its art. He thinks the greatest artistic endeavour of recent times was not a performance or a film, but Radiohead asking fans to pay what they want for their albums. Would he call himself a socialist?

“I don’t know that I would politically pin myself down in that way. We need more definitions than the old ones because the old ones carry associations for people that are now somewhat toxic, and I think somehow divisive, and socialism for some people carries a pre-Sixties definition that puts certain people’s teeth on edge, as do words like ‘conservative’. I think that labels are limiting and reductive and I wish more people defined themselves as progressive. A lot of what we are seeing in the world, politically, is not so much about left-wing and right-wing but more about progressive versus regressive vision.”

Norton searches out moments where he can engage with people. When I walk into the interview he despairs at the state of media today, especially what he sees as the commodification of news and sports journalism. He’s on the side of journalists when he complains newspapers are less and less interested in longer, more in-depth, analytical articles, the kind he likes to read. He cites a Lawrence Grobel Playboy interview with Marlon Brando in which the actor said that he found being asked his opinions on world affairs almost as ridiculous as the fact that he actually answered them. Norton doesn’t share that belief, unless he’s in a situation where journalists seemingly just read questions from a list and are not listening or responding to the answers he gives.

I first became aware of Norton’s desire for authenticity when I interviewed him for a biography on Spike Lee. Then, as today, his answers were studied, becoming of a man who went to Yale to read history. At Yale he acted in in university productions alongside classmate Paul Giamatti. We discussed Norton’s appearance in 25th Hour, but, with great vigour, Norton reminisced about the influence Do the Right Thing, Spike Lee’s masterpiece about racial tensions in Brooklyn, had on him. After watching the film, he went straight back to the box office and bought tickets to watch the film again.

Norton sent letters to Lee telling him how much he admired his work. He still sends letters to directors he admires, a trait he says makes him understand why fans want to come up to him and chat. Although he calls requests for selfies “silly behaviour”, he says most of the time it’s a “nice compliment”. It’s also why he’s happy to receive prizes such as the career award in Locarno. He says of the need to express approval of artists: “It’s a feeling I get when I watch Jacques Audiard films. I’m blown away and inspired by them and I think they are amazing, so I wrote him a letter. So I’m just saying, when people feed back, the message is received.”

This is said without Norton having yet watched Audiard’s Palme d’Or winner Dheepan. Nonetheless it leads to a discussion on identity politics. The film created a debate about this in Cannes. Using audience-theory arguments put forward by esteemed academics such as Stuart Hall, it was posited that the critical reception of the film was less than ecstatic because the majority of critics were white middle-class men, who struggled to identify with the main protagonist, a former Tamil Tiger from Sri Lanka. Norton has gone on record as saying, “we’re still having to deal with the stench of the last fart of the dying corpse of this regressive vision that America is a white, middle-aged, conservative country”.

Indeed, it’s a problem that was discussed when it was mooted that Norton should put on a theatrical production of John Osborne’s classic British drama Look Back in Anger. “People are always throwing that stuff by you, ‘what if we revived this play in New York?’. I thought about it for a second and I thought that America has no relationship to class like Britain does. But if I was directing that play I would never cast a white guy as Jimmy Porter. I would cast a brilliant Pakistani, because that’s the most live incarnation of those frictions, and especially in the globalised world, and I think Audiard is tapping into all of them.”

Having starred in films for more than 20 years, Norton has narrowed down the type of roles he wants to perform. Currently he’s preparing to direct Motherless Brooklyn, his long-mooted adaptation of the Jonathan Lethem book. It has been 15 years since he made the lightweight romantic drama Keeping the Faith. He blames the gap on the fact that he was obsessed with getting the script perfect, and quips that he’s so slow that if he were ever to write a novel, he’d be 80 and talking about it being half-finished.

He hasn’t signed on to do another movie, although he has been in discussion. Is this a sign that he has become bored of acting? “No, not at all,” he replies. “I just think that I’m less interested than I used to be in, like, exploring genre for the sake of it. I think I’ve had lots of fun working on what I would call genre pictures, heist pictures, cop thrillers and maybe you’re exercising your muscles in a certain way and trying to challenge yourself, but more and more I think I’ve just gotten more willing to wait for things that feel really strong as an attempt to make an original piece, or are expressing something that is really unique, or [are from] a film-maker that I really admire like Wes Anderson, or Alejandro Inarritu or Spike Lee.” Lovers of great acting will be hoping that the wait isn’t too long.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks