Django Unchained is the first Tarantino film released in China: Hollywood enters the dragon market but can it appease the censors?

As moviemakers look to make money in the East, Geoffrey Macnab reveals the conditions that China is imposing

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Everybody in the Western film world wants a bit of China. Hollywood studios are desperate to establish a foothold in the world's biggest-growing movie market. European countries have been clamouring to strike co-production treaties with the Chinese.

The new gold-rush mentality about Chinese cinema was reinforced last year when China (slightly) relaxed its quota laws. Now, 34 foreign films (as opposed to 20) can be distributed in the Chinese market every year.

Further encouragement to the West has come in the type of films being released. Quentin Tarantino's Django Unchained goes out in Chinese cinemas next month. This will be the first Tarantino movie to be seen officially in China. Given the level of violence in Django, its acceptance by censorship body the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television (SARFT) came as a surprise to many. Reportedly, only a minute has been cut from the film's original running time (as opposed to the 40 minutes that were lopped off Cloud Atlas earlier this year, including both gay and straight love scenes.) Historically, SARFT has been almost as fussy in what it allows on screen as Hollywood's notoriously prim Motion Picture Production Code in the 1930s. Everything from sex and violence to showing ghosts or disparaging the image of the People's Army is frowned on. There are signs, though, of a new liberalism.

The latest Bond film, Skyfall, did very brisk business when it opened in January. There were the inevitable cuts – a French hitman killing a Chinese security guard in a Shanghai skyscraper, the villain Javier Bardem's reminiscences about being tortured by the Chinese security forces, some references to prostitution – but Chinese audiences took to the internet to complain. A public debate about censorship ensued with even the official state news agency Xinhua criticising the cuts. In the social-media age, when pirated copies of films are available anyway, the authorities must realise that they can't stop audiences from finding out about or watching the original movies. James Cameron's Titanic 3D, minus the Kate Winslet nude scene but otherwise largely intact, was likewise a box-office phenomenon in China last year.

In theory, then, these are boom times for Westerners taking their movies to China. In practice, a huge wariness remains on both sides. There are still profound cultural differences to be overcome.

The Chinese authorities are intensely suspicious about outsiders who aren't doing anything to benefit the local industry. Westerners, meanwhile, are uncomfortable about the rapidly shifting ground on which they still have to operate when they do business in China.

“It is quite difficult to get a definite sign-off and approval from SARFT,” notes a former US studio executive who has worked frequently in China. “There are too many experiences of approval having been given and then taken away.”

The Chinese use a subtle kind of protectionism (reminiscent of tactics the Americans themselves once employed.) For example, last year, the China Film Group, the all-powerful state body that controls the distribution of imported films, arranged for The Amazing Spider-Man and The Dark Knight Rises to be released on the same day. This meant the two American blockbusters ate into their own audiences. At the same time, locally made films are given prime slots. But it has become painfully obvious that Chinese producers don't yet have the knack of turning out blockbusters. The hope that the success of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) would spark a new wave of global hits from China has long been dashed.

In order to get around the restrictions still routinely placed in their way, the US studios are trying to work directly with the Chinese. Fox recently announced plans to co-produce “multiple Chinese language films” with the Beijing-based Bona Film Group. Meanwhile, as The New York Times noted, when Kung Fu Panda 3 is released in China in 2016, the state censors “will find no nasty surprises” because Dreamworks has already cleared the “story line, production art and other creative elements” with the Chinese.

Ironically, Hollywood's problems haven't just come from Chinese officials but from the American government. There have been suggestions that US studios may have made “inappropriate payments” to Chinese government officials to ease their films into the Chinese market. Although no formal charges have been brought against anyone yet, it is speculated that the studios may have broken the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

“I do not believe that the studios knowingly went and slapped lots of money into government officials' hands but if you're giving money to a local distributor, that doesn't take long ending up possibly in some official's hand somewhere,” the former studio executive speculates.

With the US Securities and Exchange Commission investigating Hollywood and the Chinese censors and bureaucrats to deal with, the Hollywood studios aren't finding it easy to break into the Chinese market. Piracy remains a continuing worry. The logistics of shooting or distributing international films in China are daunting. Even so, the prize is so great that Hollywood is showing an unusual humility in its dealings.

At a US-China film summit held in Los Angeles last October, the Americans went out of their way to court Han Sanping, Chairman of the China Film Group. Rather than being criticised for making it so difficult for US films to reach Chinese audiences, Sanping was awarded the Asia Society “China Visionary of the Year Award.”

“The time to act is now,” declares Rob Cain, a producer and industry consultant who has been doing business in China since 1987.

“By 2020, the window will have closed quite a bit. Chinese producers are going to be more knowledgeable and sophisticated about the business and better able to develop projects themselves.”

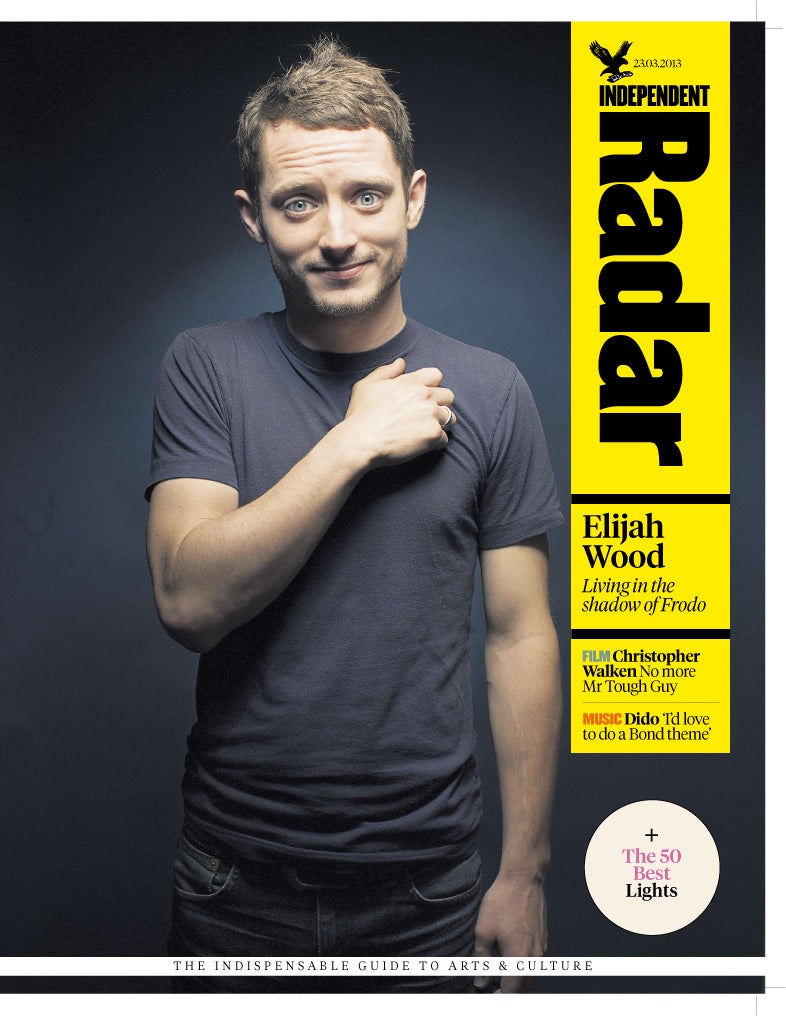

This article appears in tomorrow's print edition of The Independent's Radar magazine

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments