‘Just Keep Livin’: The enduring power of Dazed and Confused

As Richard Linklater’s woozy tour de force turns 25, Ed Power looks back at the movie's turbulent production

Towards the end of his speech accepting the 2014 Oscar for Best Actor, Matthew McConaughey tilted his head, as if gazing somewhere beyond the great and good assembled at the Dolby Theatre in downtown Los Angeles.

“Whatever it is we look up to, whatever it is we look forward to and whoever it is we’re chasing …” modern Hollywood’s great charmer said on the night he took home the gong for Dallas Buyer’s Club. “To that I say: ‘Alright, alright, alright…’ And to that I say: ‘Just keep living.’”

“All right, all right, all right“ was the catchphrase McConaughey had coined half a lifetime previously on the set of his first movie, Dazed and Confused – the woozy tour de force released 25 years ago this month. But it was “just keep living” – the closing flourish in the most important address of his life – that was undoubtedly the sentiment closest to his heart.

He had improvised this line during one of the pivotal scenes in Dazed and Confused. The film, directed by self-taught wunderkind Richard Linklater, is a bittersweet meditation on the trials and tedium of adolescence framed through the final day of high school in suburban Austin, Texas, on 28 May 1976.

Dazed would prove a springboard for a number of Nineties actors, among them Ben Affleck, Parker Posey, Milla Jovovich and Anthony Rapp (whose revelations about Kevin Spacey’s predatory tendencies led to the unravelling of Spacey’s career). Future romcom queen Renee Zellweger had a small unspoken part, too, after pleading with Linklater to cast her.

But it was McConaughey who arguably embodied both the sweetness and the sadness of the film. The famous pot-smoking post-party sequence at the 50-yard line of the school football pitch was the first McConaughey had shot upon returning to the set following the death of his father. It had been sudden (McConaughey’s mother would later claim it occurred mid-coitus) and Matthew was required to drop everything and travel 300 miles from Austin to the family home at Longview, Texas.

The character he had been playing, David Wooderson, was the stereotypical big guy in a small town. Rather than face adulthood he preferred chasing teenagers – “that’s what I like about these high school girls, I keep getting older, they stay the same age” – and had somehow convinced himself his best days were ahead rather than vanishing in the rearview mirror. Anyone growing up in the sticks will have recognised the archetype immediately.

A less insightful actor might have portrayed Wooderson as a loser. McConaughey, showing glimmers of the instincts that would soon make him a movie star, located a nobility in Wooderson’s low aspirations (his eureka moment when playing Wooderson was walking with his pelvis thrust outwards; this was a guy who confronted life crotch-first).

But now, as Wooderson kicked back on the football field with a rag-tag of high-school seniors, including the movie’s putative hero Randall “Pink” Floyd (Jason London), McConaughey found the death of his dad rushing towards him.

“Let me tell you this, the older you do get the more rules they’re gonna try to get you to follow,” Wooderson tells Floyd, who is agonising over whether to sign a pledge to abstain from fast living while playing for the school football team. “You just gotta keep livin’ man, L-I-V-I-N.”

The words had come to McConaughey on the fly, as his character’s lunk-headed optimism crashed into his grief over his father. Twenty-one years later, as he stood centre stage at the Academy Awards, a little part of him was still back on that 50-yard line in Texas, still vowing to keep on doing it for his old man.

“Just keep livin’” was merely one profound moment among many in a film that elevated the premise of the “movie about nothing” into heartbreaking art. At one level, Dazed and Confused truly is about nothing. The high schoolers it portrays are by turns bored, cynical and violent – brief sketchings rather than substantive characters.

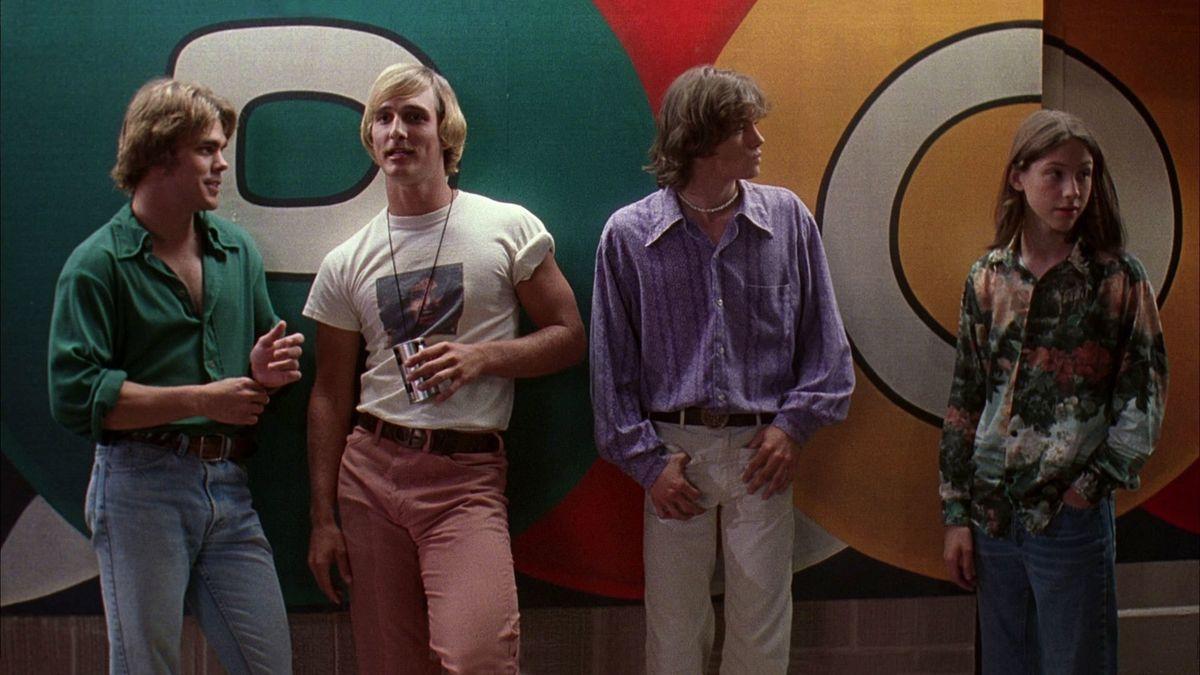

Equally negligible is the plot. School’s out for summer, and bullies, led by 20-year-old Ben Affleck’s cocksure Fred O’Bannion, are chasing a new crop of incoming freshmen – including Mitch Kramer (first-time actor Wiley Wiggins) – in order to inflict a ritualistic hazing. Meanwhile, star footballer Floyd is wrestling over whether to sign his coach’s abstinence pledge. In the end, he declines and drives out of town with friends, Wooderson among them, to purchase tickets for an Aerosmith concert.

Yet from these mundanities Linklater wrangles truths both profound and universal. He brings us life as it truly is lived: randomly, alternating between transcendence, frustration and boredom. Who really has a handle on what’s going on? Floyd, fretting about what tomorrow holds and convinced there must be something better out there? Or Wooderson, strutting towards the future with his lips curled and crotch tilted forward?

The film was intensely personal for Linklater. Following the success of his super lo-fi 1990 hit Slacker – shot on the hoof around around Austin with a largely amateur cast – he had conceived of Dazed and Confused as a warts-and-all riposte to the nostalgic vision of small-town USA.

That was the version presented in George Lucas’s American Graffiti, one that ran contrary to Linklater’s own adolescence in Seventies Austin. Linklater had witnessed the same ritual floggings that O’Bannion inflicts on Kramer and had even gone to school with a Richard Floyd (Floyd and two other classmates name-checked on screen were not impressed at Linklater’s homage to their carefree youths, and sued for defamation).

Yet, somehow, the movie he made was as much about the decade in which it was shot as that in which it’s set. Dazed and Confused is undoubtedly one of the great high-school capers while also functioning as an avant-garde deconstruction of the high-school caper as a genre (in the original script the entire film is shot inside a car as the characters mooch around town listening to ZZ Top).

But watched today, it’s the incredible Nineties-ness of the endeavour that stands out (and that despite a soundtrack stuffed with Seventies signifiers such as Grandfunk Railroad and Foghat rather than Nirvana, Hole and Smashing Pumpkins).

Partly, it’s down to the cast. Playing bully-boy O’Bannion’s female counterpart, Darla Marks, Parker Posey couldn’t have looked more grunge-era had she worn a Nevermind T-shirt and an “I Heart L7” lapel badge. As a paddle-happy thug, Affleck, for his part, foreshadows the arch-bro persona of Pearl Harbour and Armageddon.

And what could be more Nineties than Dazed and Confused’s lackadaisical tempo – an artful eye-roll perfectly attuned to the Gen X sensibilities of Douglas Coupland, shoegaze-rock and Kurt Cobain’s disavowal of stardom?

It’s a testament to Linklater that he could conjure this laid-back sensibility while, in real life, fighting a rear-guard battle with the Hollywood studio that had stumped up the movie’s $6.9m budget. Just 32 years old, the filmmaker was in constant conflict with his producers, who pressured him to save money and time by dropping scenes and cutting dialogue.

“Our ridiculous schedule means basically having to do a day and a half’s work every day,” he would write in a series of diary-like pieces published in the Austin Chronicle throughout the summer of 1993. “I go in with my shot list and get to spend lunch hearing how we can’t get all of it because we can’t have any overtime or meal penalty.”

Dazed and Confused was, in in addition, an early showcase for the naturalistic dialogue that would become recognised as one of Linklater’s signatures. He refined the technique with his Before Sunrise/Sunset/Midnight trilogy – which tracks the relationship through real time of young lovers-turned-weary spouses played Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke – and the Oscar-nominated Boyhood (2014).

But it’s all there, fully formed, in Dazed, where the script serves as a starting point rather than scripture, with Linklater encouraging the cast to ad-lib and to speak how they felt their characters would really communicate. He recalled one scene where, standing in the wings, he constantly riled up Affleck, in order to whip O’Bannion into a condition of supreme nastiness.

“I’m interested in the reality of [the] actors on the screen, so I know that you can’t just say lines written by someone else,” he would later say of his working method. “The text – the script – has to work through the person.”

Tension between Linklater and his Hollywood handlers, as represented on the ground by producer James Jacks (Raising Arizona, Hard Target) came to a head one night during the filming of a scene in which Affleck’s O’Bannion has a bucket of paint poured over his head. Unbeknown to Linklater, Daniel had been going behind the director’s back and pleading with Affleck to tone down the expletives he was sprinkling through his largely improvised dialogue.

The message appeared to have not quite landed. “Cocksucker!” yelled Affleck during the sequence, prompting Jacks to later grab the future Sexiest Man Alive by the lapels.

“He’s like, ‘I can’t believe you would do that,’” Linklater said. “‘That’s worse than f***…’ I thought f*** is the worst word. He was like ‘cocksucker is the worst word.’”

The mood music had been very different six months earlier when, on the strength of Slacker, Linklater was invited to Hollywood to share ideas for his next project.

“The first-class ticket, the limo, the Chateau Marmont … I’m having lunch at the Universal dining room with Jim Jacks,” Linklater would write in the Austin Chronicle. “We’re going to have a more official meeting with more people later but, for now, we’re just shooting the shit. Jim looks the exact opposite of what I thought a Hollywood executive would look like. He’s large, no tie, not well-dressed – my kind of guy.”

As the glad-handing proceeded, though, it dawned on Linklater that studio and director were not necessarily on the same page. Universal envisaged a cheap teen comedy directed by a buzzy newcomer. He imagined something else entirely.

“I sense what everyone wants to talk about is the film’s inherent commercial potential and then hear me tell them how much it means to me personally.

“That’s always the correct Hollywood order – money, money and then maybe a decent movie that might mean something to you too,” he recalled. “We talk about teen movies we’ve liked – I soon have to drop Over the Edge, River’s Edge and certainly Los Olvidados from my list of favourite teen movies.

“Rule No 1 – never like or discuss in positive terms a movie that didn’t make lots of money. A great movie that, maybe, breaks even isn’t any good until a decade later. And never mention that you might like foreign films – you’re an immediate suspect. So, for now, it’s the obligatory American Graffiti/Fast Times at Ridgemont High/Breakfast Club references.”

Yet, it was only in post-production that his relationship with the executives would really come under strain.

On set in Austin, the atmosphere was generally upbeat and playful. That was to a large extent a consequence of the extreme youthfulness of the cast. With up-and-comers from Los Angeles and New York, supplemented by local kids, often recruited on the street (Wiley), the atmosphere was of one endless summer sleepover. Headquarters for most of the actors was the Austin Radisson – where late-night partying, enthusiastic canoodling and heroic consumption of booze and pot did little to endear them to the staff.

“We all decorated our rooms and moved our beds around, hung tapestries, and burned incense,” said Michelle Burke, who played Mitch Kramer’s drop-dead cool older sister Jodi. “We were like kids in a candy store. Actors were hooking up with each other and dating,” said Rory Cochrane (who played stoner Ron Slater).

Occasionally, matters got out of hand. Tension between actor Shawn Andrews (Kevin Pickford, whose plans for a keg party are rumbled by his parents) and the rest of the cast led to his character being more or less excised from the story. Not that Pickford was too bothered – shortly afterwards he and his 16-year-old co-star, future Resident Evil actress Milla Jovovich, eloped to Los Vegas and were married (Jovovich’s mother tracked them down and saw that the nuptials was annulled).

Already a well-known model, Jovovich featured heavily in the promotion of the film. As a budding musician, she was also pleased that Linklater allowed her perform one of her songs on screen. So she was understandably miffed to discover that, as with Pickford, most of her scenes had been edited out (the director felt her character had failed to “gel”).

One reason they were marginalised was because another star had glimmered into view – McConaughey’s Wooderson, originally written by Linklater as a minor player. The apocryphal story of McConaughey wangling his way into the picture after a hotel-bar run-in with legendary casting director Don Phillips – who’d discovered Sean Penn when casting Fast Times at Ridgemont High in 1982 – is part of Hollywood folklore. Nevertheless, it’s clear nobody involved in the production had an inkling what they were in for.

“He came in so locked-and-loaded,” remembers Jason London of McConaughey. “You met this guy who seemed kind of normal, and we started to rehearse and his demeanour slumps, his eyes droop – he got that stoned smile on his face and delivered that ‘heyyyy’ voice. We were just in heaven.”

That McConaughey was more than just a charmer became quickly obvious too. In addition to improvising the “just keep livin’” speech, he also gave Dazed and Confused its great catchphrase when he pulls up to a drive-through and greets smarty-pants student Cynthia Dunn (Marissa Ribisi, future wife of musician Beck Hanson) with the immortal line “all right, all right, all right”.

The words were cribbed from a Doors album, Live in Boston, that McConaughey had listened to preparing for the scene. “All right, all right, all right, all right…” screams Jim Morrison, at full demented rock-god tilt. McConaughey discerned something in the tirade beyond the Lizard King’s egomania: a lust for living that spoke to him and, he suspected, to the Wooderson character.

“I’m in my car; I’m high as a kite; I’m listening to rock and roll,” is how he recalled improvising the line. “Action! And there’s the chick – ‘All right, all right, all right!’ Three out of four!”

Shooting concluded in August 1992 and the cast went off to the rest of their lives. Some – Affleck, McConaughey, Zellweger – graduated to full-fledged stardom. Others tried and failed. “I just wasn’t quite good enough,” concluded Christin Hinojosa (Sabrina Davis), who moved to Hollywood after Dazed and Confused and went an entire year without work. Today, she is an anti-war activist.

However, for Linklater the struggle had only begun. A test screening in Dallas was disastrous – though he suspected the studio had erred in recruiting a small, listless audience on an afternoon in which the Dallas Cowboys were playing. Meanwhile, disagreements over the soundtrack almost led him walking away from the project entirely.

Dazed and Confused was named after the Led Zeppelin hit and Linklater was keen for the song to play over the final credits. When Led Zeppelins’s publishers gave him a flat “no” he recorded a five-minute personal plea to Jimmy Page and sent the cassette, along with a handwritten letter and excerpts from the movie, to the guitarist. The answer duly came back in the affirmative. Unfortunately, when he attempted the same tactic with Zeppelin frontman Robert Plant, the response remained negative – which did not endear the leonine rock god to the obscure filmmaker from Texas.

“I sent a similar video to the one I sent to Page,” he wrote in a diary entry. “I’m not sure if Plant ever saw it himself. His “keepers” are much more negative and less helpful than Page’s. I’m even making desperate calls to his manager’s next-door neighbour in London. We’re out of time, so two days before the absolutely final mix, I throw in the Zeppelin towel. I’ve never worked so hard for something like this and not gotten it. I’ll boycott Plant for life."

Another source of conflict was a push by the studio to tie-in Dazed and Confused with a new band signed to Universal off-shoot Geffen. The idea was for hard-rockers Jackyl to performer a cover of Grand Funk Railroad’s “We’re an American Band” over the closing credits – a crass stunt that horrified Linklater (it didn’t help that the Jackyl’s biggest hit was “She Loves My Cock”). He was so aghast that he wrote to Jackyl begging them to cry off. They assented – at the cost of their contract with Geffen.

“They got my letter, pulled out of the deal, which I can only respect on an integrity level, and then the album deal collapsed. I know this is going to be a huge mess, but I don’t care – my budding stomach ulcers practically disappear instantaneously. “

Linklater was by this point living in an apartment in the remote LA suburb of Oakwood, spending his days at a downtown editing suite and trying to retain the vestiges of his sanity. How much of it remained by the time he delivered his 102-minute cut of Dazed and Confused is difficult to say.

To its credit, the studio put out the movie he had wanted to make. However, there was no final vindication, not in the short term at least, as Dazed and Confused underperformed disastrously, bringing in just $8m. The fault, as Linklater saw it, was the decision to put it out via Universal’s new arthouse distributor Gramercy, which earned underground kudos but also meant a limited release. It did not help the reviews were generally lukewarm rather than rapturous. The doyen of American film criticism, Roger Ebert, was positive towards Dazed and Confused but clearly did not regard it as worth championing.

“The film is art crossed with anthropology. It tells the painful underside of American Graffitti,” he observed in a measured, three-star write-up. “This is a good film, but it would not cheer people up much at a high-school reunion.”

However, as with many great movies from the Nineties, Dazed would quickly find its fanbase on video and later DVD and through repeat screenings on American cable TV. To the audience who discovered the film after the fact, it was obvious that Linklater, with his meandering style and rejection of conventional structure, had caught an essence of growing up – the sense that the best days of your life aren’t all that fantastic.

Before long it was an acknowledged classic. And it was a stepping-stone for Linklater, who would have an old-fashioned Hollywood hit 10 years later with School of Rock (in 2016, he would return to Dazed’s small-town Texas setting via the unofficial sequel, Everybody Wants Some, which chronicles several days in the lives of four college freshmen). But it was also a something special, and enduring, in its own right.

“The film is made up of a succession of small visions, observed and executed with apparent ease but thought through with such exquisite care and attention that the experience becomes overwhelming,” essayist Kent Jones would observe introducing the 2006 Criterion Collection’s DVD edition of the movie.

“Did Linklater instruct his actors in the correct way of leaning against a wall? Probably not, but then it’s the fact that doing nothing occupies the centre rather than the periphery of the movie that gives such moments their verisimilitude.” Never before or since would simply doing nothing feel so artful and honest.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks