'If movies disappeared overnight, I wouldn’t care': David Cronenberg on the death of cinema

The 75-year-old director on how the big-screen experience is ‘shattering into a million small screens’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

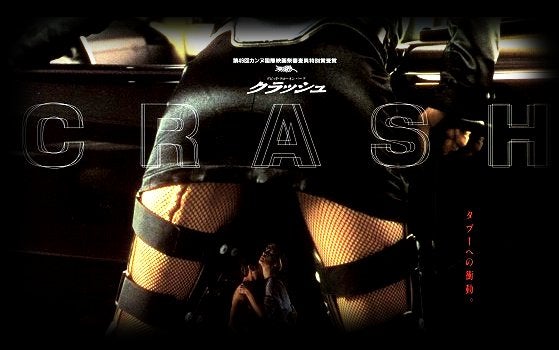

Your support makes all the difference.David Cronenberg, the venerated director of such films as Crash, The Fly, Naked Lunch, Rabid and The Brood, will be travelling to Venice next month to accept a Golden Lion award for “lifetime achievement” in cinema. The irony is that the 75-year-old Canadian director appears to be losing his faith in the medium in which he has excelled for so long at the very moment his career is being celebrated.

“If movies disappeared overnight, I wouldn’t care. The cinema is not my life,” Cronenberg recently observed. This high priest of “body horror” describes the current predicament of cinema in just those terms: in the age of the internet, Netflix and streaming, he believes, “cinema is dissolving, the big screen is shattering into a million small screens”. Like the human body, it is “evolving and changing”.

Interviewed this month at the Neuchatel International Fantastic Film festival (where he was president of the jury), Cronenberg seemed utterly sanguine at the idea that cinema as we used to understand it is in its death throes.

“It’s not that I need it to die or change. I am just observing it – and observing it in myself. At a certain point, I just stopped going to cinema for various reasons.”

Somewhat banally, it was the car parking problems that put him off. And he doesn’t like the commercials before the features. In the middle of a cold Toronto winter, he prefers to “burrow himself in” and watch his 50-inch Panasonic plasma.

“I don’t go to the cinema any more,” the director declares. He adds that it is almost a novelty for him to be watching 16 movies in his capacity as president of a festival jury; that is far more than he has seen in cinemas in recent years.

But the important distinction he wants to make is that filmmaking isn’t “dead” – it is just that cinema is no longer “the cathedral that you go to where you commune with many other people”.

Instead, you watch on your laptop, TV or handheld device. He suggests that watching a film on an iPad is closer to reading a novel than it is to the old cinema-going experience.

In his work, Cronenberg has always been a subversive and visionary figure. So it is surprising to encounter him in the flesh: he’s courteous, seemingly easy-going, and very unpretentious.

Another surprising aspect to this self-confessed “technology and science nerd” is his passion for literature. He speaks every bit as passionately about the work of Vladimir Nabokov and Djuna Barnes as about the filmmakers he admires.

In Neuchatel, the Canadian director took part in a Q&A on “How Literature Has Consumed The World Of David Cronenberg”, at which he discussed his 2015 debut novel Consumed at length, as well as his adaptations of the work of William Burroughs and JG Ballard.

The book, about a pair of gadget-obsessed, hipster journalists investigating the death of a Sartre-like French intellectual, is full of references to cinema. Characters are likened to French movie stars like Simone Signoret and Jean-Pierre Leaud. Paragraphs begin with instructions (“cut to a wide shot”) that could come straight from a film script.

For Cronenberg is still open about the huge influence cinema has had on him since a young age. It was a transformative moment in his life as a kid when he crossed the road from his local movie theatre The Pylon (where he used to watch Roy Rogers cowboy films and cartoons) to go to the Studio, a rival cinema which catered for Toronto’s huge Italian population. He had seen adults coming out of the cinema weeping and had gone to investigate.

That is how he stumbled on Federico Fellini’s La Strada and had his first inklings of the “great power” of cinema to play on audiences’ emotions.

“But I don’t have this nostalgia for the technology,“ he explains. ”I was incredibly happy to get rid of typewriters, for example, even though you can see there is an affection for typewriters in Naked Lunch. Really, it was much better when computers happened. I couldn’t wait for that, for word processing. It’s more like the way your mind works instead of a machine.

“I like the machine as an art object but I don’t ever want to have to use a typewriter again to have to write something.”

Still, typewriters have a totemic significance in Cronenberg’s life. His father Milton Cronenberg was a journalist and crime writer who wrote everything from financial reports to long, learned articles about stamp collecting.

When David was in bed at night, he could hear his father pounding away on the keyboard of his old Underwood. His father also shared his son’s fascination with new technology and was one of the first Canadians to own an electric typewriter.

Cronenberg’s parents were atheists and encouraged their son when he showed an interest in philosophy. “I came to feel that the art most interesting to me was art which provoked philosophical thought. People have said to me ‘in your movies, you really want to scare people’. I don’t even think about that. For me, making a film is a philosophical voyage.”

That voyage has occasionally taken him to Hollywood. His most recent feature, Maps To The Stars (2014), presented a searing and prophetic picture of a US studio system in which corruption and abuse are endemic (the film seems even more topical now, given the Weinstein scandal, than it did at the time of its release). Cronenberg credits his screenwriter on the project, Bruce Wagner, with the film’s particularly bleak vision of Tinseltown.

However, the Canadian has had his share of bruising moments in Hollywood. At one stage, he was on board to direct the Philip K Dick adaptation Total Recall, with William Hurt in the lead role. In the event, Paul Verhoeven completed the job with Arnold Schwarzenegger in the lead.

“What happened was that [producer] Dino De Laurentiis’ company went bankrupt and so the project disappeared. I never did get to make Total Recall. If I had done, it would have been quite different from the movie that resulted although there are some scenes in that movie that I wrote.”

He has always accepted that the “Hollywood version of movie making is very difficult”. Even the biggest name directors like his friend Martin Scorsese struggle to secure financing and full creative freedom on their projects. “People think, well, Marty, he’s famous; he has won this and that – he can snap his fingers and get anything made. Of course, it is absolutely not true. It is always a struggle.”

Cronenberg isn’t sentimental about what happens to his own films either – a good job as there are plans afoot to remake many of them. Rabid, Videodrome, The Brood and Scanners, among others, are all being rehatched either as features or TV dramas. There has long been talk of a new version of The Fly.

“I don’t have either a financial or a legal interest in these movies and so if they happen, they happen,” he states in matter-of-fact fashion, as if it is a matter of indifference to him.

There came a stage recently when he decided that he had had enough of filmmaking; that he would concentrate instead on writing.

“I was starting to feel that there were some things I wanted to express that I could not express in cinema,” Cronenberg says, when discussing why he turned to novel writing. “In a way, the cinema is a very crude thing… there are certain things a novel can do that have to do with interiority of thought and emotion that you cannot express in cinema.”

However, thanks to Netflix and long-form TV drama, Cronenberg is currently rethinking his approach to filmmaking.

“I have some things I want to say and there are three ways I could do it. One would be to make a movie, one would be to write a novel, and one would be to make a series.” He won’t reveal details of the project – but the TV option clearly now appeals.

When Cronenberg turns up at the Venice Film Festival next month to pick up his lifetime achievement award, it may well seem like a step back into the past. “There will always be retro things. It’s like people going back to vinyl records. There will always be some cinema somewhere showing a movie and they’ll dig up a 35mm print,” he says of the enduring appeal of cinema.

In Neuchatel, he was invited to programme some of his favourite films. He chose, among others, Fellini’s Toby Dammit, Jack Arnold’s The Incredible Shrinking Man, Ingmar Bergman’s The Hour Of The Wolf, and Teshigahara Hiroshi’s The Woman In The Dunes.

And the passion with which he discusses these movies suggested that, for all his talk of cinema dying, he himself hasn’t lost the faith quite yet.

David Cronenberg was president of the jury at the Neuchatel International Fantastic Film Festival

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments