Why film-makers cut movies after their premieres

Inside Film: ‘The Current War’ starring Benedict Cumberbatch is almost two years old but has been re-edited since its first showing

In normal circumstances, the arrival of a big new movie about inventor and electricity pioneer Thomas Edison, and starring Benedict Cumberbatch, would spark considerable excitement. However, in advance of its release, The Current War (out in the UK this week) isn’t generating nearly as much buzz as might have been anticipated. Dimming anticipation is the fact that the film is already almost two years old.

The posters fail to mention that The Current War first flickered into life at the Toronto Festival in the early autumn of 2017. Back then the film, which was originally scheduled to be released by the Weinstein Company, was being talked about as a likely Oscar contender. That was before the lacklustre reviews and the Harvey Weinstein scandal combined to extinguish any hope of awards. The Weinstein Company collapsed into bankruptcy, leaving the film without a distributor. When I interviewed its producer, Russian film-maker Timur Bekmambetov, last year, he claimed that The Current War had premiered in Toronto in an “unfinished” version anyway.

Director Alfonso Gomez-Rejon appeared to have been pressured by Weinstein to complete The Current War in time for its Toronto premiere. However, he has now been able to restore “the heart of the film” (as he has told the press) and to “fix” its problems by adding some new scenes, while slightly shortening the running time.

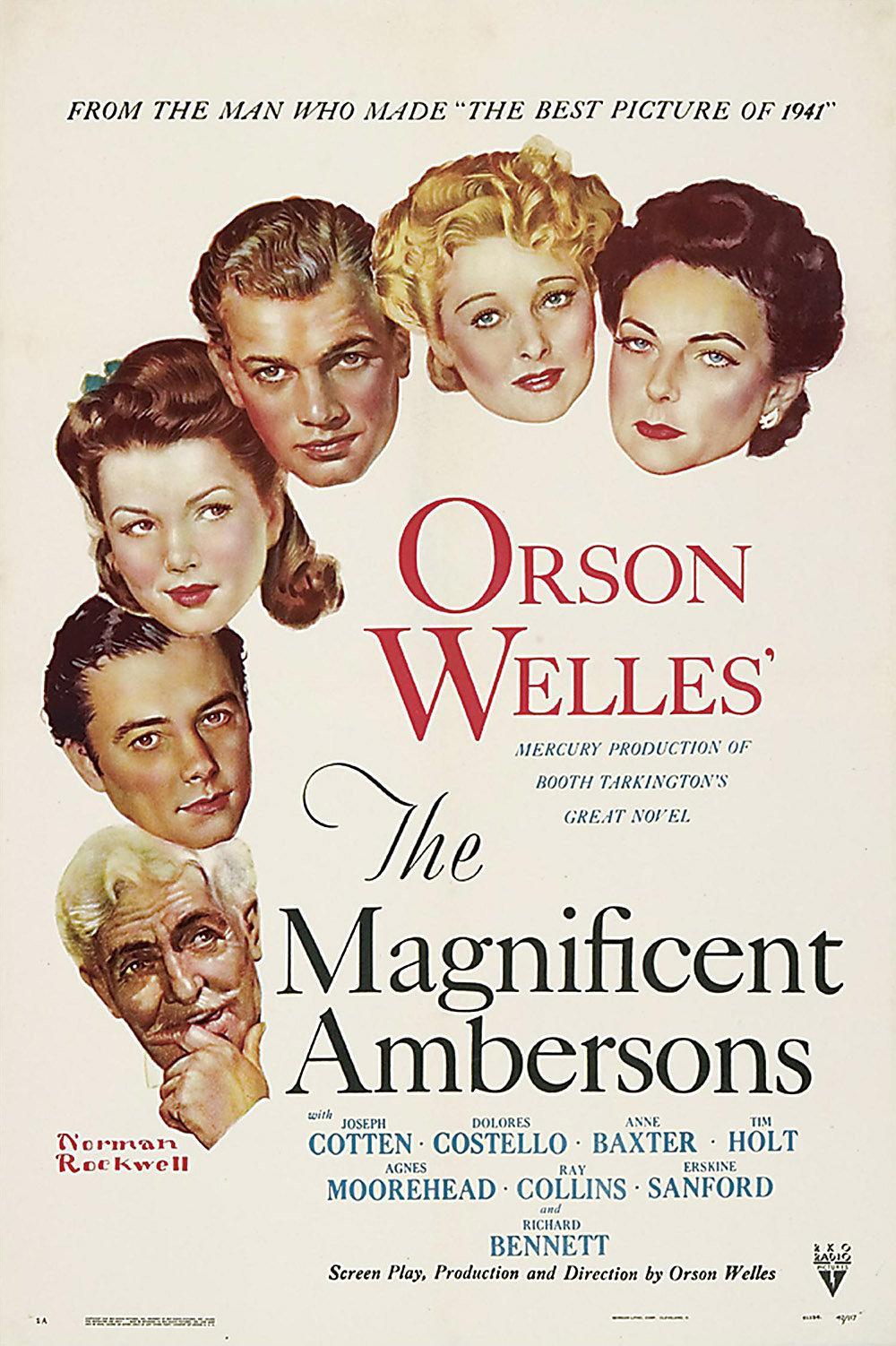

Cinema history is littered with stories like this. Films endure hostile receptions at their premieres and are then given shock treatment in a desperate bid to make them fit for release. It happened to Orson Welles’s second feature, The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), previewed in front of a rowdy young Saturday night audience in Pomona, California, as part of a double bill with The Fleet’s In (1942), a frothy Dorothy Lamour musical.

Asked to fill out cards saying if they had liked Welles’s dark and brooding movie about an American family squandering its fortune, most spectators were determinedly negative.

“The worst picture I ever saw,” was one response.

“Too many weird camera shots. It should be shelved as it is a crime to take people’s hard-earned money for such artistic trash,” was another.

RKO Pictures set to work with the scissors on Welles’s film, which was eventually released in a bowdlerised version, under 90 minutes long – as opposed to the director’s original cut of 131 minutes. “As a cinematic achievement, it was undoubtedly a better film in its original length, but it just didn’t play to an audience,” Robert Wise, who edited it, later justified about the changes. Welles himself was in Rio at the time, working on his equally ill-fated documentary It’s All True (1942) and was powerless to stop them. Unlike Gomez-Rejon, he wasn’t given the chance to make the changes himself.

Welles enthusiasts continue to travel to Brazil in search of the original version of The Magnificent Ambersons, a copy of which the studio sent to the director in Rio. That copy was almost certainly destroyed but the “Wellesians” (as the director’s fans call themselves) cling to the faint hope it may turn up somewhere.

An equally forlorn case was Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate, which premiered in New York in 1980. Critics who felt that they had over-praised Cimino’s previous film, the Oscar-winning The Deer Hunter (1978), queued up to demolish its successor. “Watching the film is like a forced, four-hour walking tour of one’s own living room,” was reviewer Vincent Canby’s famous put-down in The New York Times. Cimino reacted by cancelling the release and desperately re-editing and shortening his own movie but he only succeeded in making it worse.

In the case of The Magnificent Ambersons and Heaven’s Gate, their troubled beginnings are part of the mythology that now surrounds them. Both are viewed as victims of bad timing. The Magnificent Ambersons was never likely to strike a chord with a wartime audience looking for escapism. Heaven’s Gate, which notoriously brought United Artists to its knees, was seen as a symbol of studio excess and decadence. If these films had been released at different times and in different circumstances, their reception would almost certainly have been far more positive.

Cimino and Welles apart, the tendency to re-edit films after their premieres is far more commonplace than might be expected. Directors working to tight deadlines will often rush the job to be ready for festivals or awards consideration. Once they see their film with an audience, they spot its flaws and try to address them. Either that or the studio deems the film too long and too self-indulgent and demands that it be shortened. By then, though, the reviews for the original version are already out. Persuading audiences to look at movies with fresh eyes then becomes a considerable challenge.

The Dardenne brothers re-edited their 2016 feature The Unknown Girl after it received a muted response in Cannes. It was too late, though, to change perceptions that had been formed when the film was first unveiled to the critics. Oliver Stone has made several different cuts of his ill-fated sword and sandal epic, Alexander (2004), starring Colin Farrell as the beach blonde Macedonian warrior king, without significantly changing anyone’s opinion that it’s a bit of a Grecian mess. There was the original cut, 175 minutes long; next, there was the Director’s Cut, a little bit shorter; soon after followed Alexander Revisited: The Final Unrated Cut (40 minutes longer) and then there was The Ultimate Cut, even longer. It was the cinematic equivalent of putting a piece of clothing through multiple different washing cycles and then discovering the stains still hadn’t come out.

Mike Hodges’ 1999 film Croupier (receiving a 20th-anniversary screening this weekend) is an example of a film disowned by its producers before it even had the chance to be shown. An existential thriller about a writer (a youthful Clive Owen) who works in a casino, it was shunned by pretty much everyone involved in it. Backers FilmFour refused initially even to release the film. “If the person who has commissioned the film doesn’t want to do it, it is unlikely that anybody else will want to do it,” the director reflects today.

By chance, the British Film Institute was about to reissue Hodges’ Newcastle-set gangster classic, Get Carter (1971), and agreed to give Croupier a limited release at the same time. It, therefore, avoided the ignominy of going straight to video. The film was eventually shown in the US, where it developed a cult following and grossed over $7m (£5.6m) at the box office, a very fair return on a modestly budgeted British feature. Hodges saw none of the profits. This, though, is still a rare example of a film that had been abandoned but which went on to have an afterlife – and Hodges didn’t even have to re-edit it to transform its fortunes.

Occasionally, film-makers will tinker away at their own movies even when they have been successful. Quentin Tarantino is rumoured to have tweaked his latest feature, Once Upon A Time... in Hollywood (out in the UK in early August) in spite of the rapturous response it received from critics when it premiered in Cannes in May. True to form, the maverick American director appears to have lengthened the movie by a few minutes rather than shortened it.

Francis Ford Coppola is another director who can’t leave his own work alone. He has released his Godfather cycle in various different configurations. His epic, mind-bending Vietnam war movie, Apocalypse Now also continues to evolve. It premiered in Cannes in 1979 in an unfinished version as a “work in progress”. It shared the festival’s top prize, the Palme D’Or, with The Tin Drum, even though it wasn’t yet complete.

Forty years later, Coppola still doesn’t seem to have finished it to his satisfaction. He released an extended version, Apocalypse Now Redux, in 2001, with 49 minutes of extra material. Next month, it is being re-released yet again as Apocalypse Now: Final Cut, in a digitally restored version “delivering spectacular colours never before seen on a screen, with highlights that are up to 40 times brighter, and blacks that are 10 times darker”.

Many cult movies, from Donald Cammell’s Wild Side to Sam Fuller’s The Big Red One, have only been restored after their directors’ deaths. With The Current War, Gomez-Rejon was given the chance to rework his film a few months after its launch. This wasn’t because the film’s new distributors wanted a director’s cut. As Gomez-Rejon explained recently to Deadline Hollywood, there had been a cock-up in the paperwork. Not all of the required contracts had been signed. Martin Scorsese, one of the executive producers, was, therefore, able to block the release until Gomez-Rejon made his desired changes.

So what’s The Current War like in the rewired version? It’s not the luminescent masterpiece anticipated when the project was first announced, but it has a few bright moments. Michael Shannon shines as Edison’s stoical and cunning rival, George Westinghouse. It is also the most intriguing movie you’re ever likely to see about utility provision and the battle between gas and electricity to “power the new century”. The story flickers into life now and again as the inventors electrocute horses or fight over patents and ideas. However, its prospects at the box office are still on the dim side. Two years on from when it was first unveiled, the film, in spite of its title, simply doesn’t seem current enough.

‘The Current War’ is out on Friday. The 20th-anniversary screening of ‘Croupier’ will take place at Cinema Rediscovered at Watershed Bristol on Saturday followed by a Q&A with Mike Hodges hosted by Samira Ahmed

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks