Why a film about the next American Civil War is Alex Garland ‘hotwiring’ the zeitgeist once again

Using the mob charging Capitol Hill as a jumping-off point for his latest film, British writer and director’s Alex Garland imagines a team of journalists travelling across the United States during a rapidly escalating Second American Civil war. Geoffrey Macnab looks back at the career of one of the UK’s great modern auteurs and why this latest work could be his most controversial yet

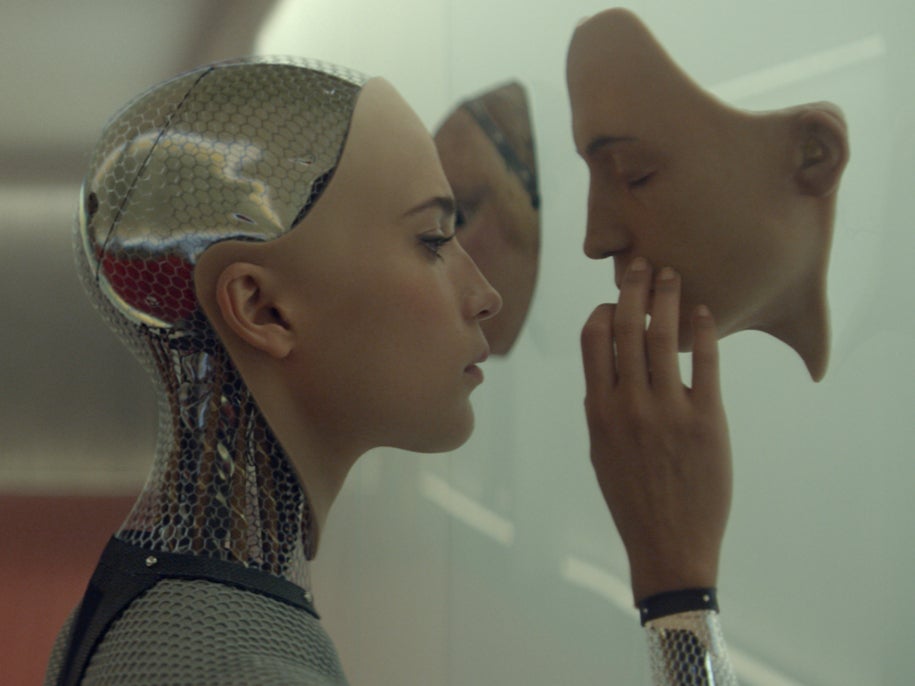

The turmoil in Washington, DC on 6 January 2021 has nothing on Civil War. If the mob of Trump supporters descending on the capital sparked (ultimately short-lived) fears of open warfare between the US’s feuding political factions, then Alex Garland’s new film brings that carnage to fruition. The British writer-director of Ex Machina (2014) and Annihilation (2018) has set his movie during a second US civil war, one which pits an authoritarian government ruled by Nick Offerman against the “western forces” from Texas and California.

The dystopian drama, also starring Kirsten Dunst, Wagner Moura (Narcos) and Cailee Spaeny (Priscilla), unfolds in a near and horribly plausible future. Nineteen states have seceded from the Union. Americans are killing Americans. Our protagonists are journalists, embedded with the military and racing against time to reach DC before the rebel factions get there.

Filmed back in the middle of 2022, Civil War (out in cinemas on Friday) has been ready for some time. But its release has seemingly been timed by distributor A24 for maximum impact in North America: the film arrived days before the US Supreme Court hearing into Donald Trump’s claim of presidential immunity on charges that he tried to overturn the results of the 2020 election.

For years, Garland, now 53, has been the unsung master of British genre cinema, a cut-price Kubrickian visionary writing and directing grungy movies on indie budgets. But Civil War could see him break through as a major mainstream director. You can’t help but admire his chutzpah.

The north London filmmaker started out as a novelist. By his mid-twenties, Garland was already a bestselling author with a cult reputation, thanks to The Beach – a hit novel that spawned a brand-new genre, so-called backpack fiction. Now, he’s made an explosive $50m (£39m) thriller that should appeal both to fans of action cinema and anyone interested in the vexed and distorted world of contemporary US politics. But it’s also bound to rile people.

In his earlier horror and sci-fi films, Garland dealt with zombies, clones and psychotic killers – sometimes all at once. He’s not averse to splatter and gore but his work has intellectual rigour too. His grandfather was Nobel prize-winning biologist Sir Peter Medawar, the so-called “father of transplantation”, and his father is the renowned British political cartoonist, Nicholas Garland. With this lineage, perhaps it’s no surprise his movies are vivid, sharply drawn affairs, touching on big themes.

In Ex Machina (2015), his first official feature as director (although he directed part of 2012’s Dredd uncredited), Garland tackled AI and robotics. Domhnall Gleeson starred as Caleb, a 24-year-old computer coder performing the Turing test on a female robot (Alicia Vikander) to establish whether she can think and feel like a human. In Annihilation (2018), a psychedelic sci-fi horror featuring Natalie Portman, he probed away at the morbid fascinations humans have with their own self-destruction. In Men (2022), he explored gender relations and the darkest most disturbing aspects of the male psyche, through the perspective of a young widow (Jessie Buckley) sojourning in the country.

Naturally, genre fans are drawn to such stories – but so are academics. His admirers include figures such as theoretical physicist and cosmologist Lawrence Krauss and computer scientist and podcaster Lex Fridman. “He’s incredibly interesting, thoughtful and self-deprecating,” Krauss enthused, after speaking to Garland for a 2022 episode of his The Origins podcast. “I am a big fan of how Alex weaves science and philosophy into his work,” Fridman added, describing his meeting with Garland as having been “life-changing”.

Their conversations make for disconcerting listening: not simply idle movie chat but high-minded scientific discourse. The director talks confidently about such matters as quantum physics, determinism, artificial intelligence, machine learning, and the nature of consciousness, easily holding his own among the experts.

Garland was only 24 when he wrote his breakthrough novel The Beach (published in 1996 and made into a film by Danny Boyle, starring Leonardo DiCaprio, four years later). The book was a phenomenon. Critics described it as a cross between William Golding’s Lord of the Flies and Donna Tartt’s The Secret History. Its young author was instantly labelled a spokesperson for the slacker generation – an irony given that he had actually written the book as a critique of the backpacker scene.

Whatever his motives for embarking on The Beach, Garland captured perfectly the ennui, fatalism and emotional vulnerability of his pampered young protagonists. What begins as a Thai getaway on the most beautiful and exotic island imaginable turns out to be a holiday in hell, as his gap-yearing protagonists attempt to make sense of their lives and drive themselves mad in the process.

I thought: Jesus Christ, I do not want to spend the next 40 years stuck in a room

Fellow novelist John Niven commented on Garland’s uncanny knack of “hotwiring the zeitgeist” – something he’s continuing to do with Civil War. As Niven put it: “for Generation X in 1996, there were no wars to fight. Only the war against boredom.”

Garland’s publishers promoted him as the moody young rebel of British literary fiction, as if he were the 1990s’ answer to F Scott Fitzgerald or James Dean. It was at this point, though, that Garland abruptly turned his back on novel writing.

“I thought: Jesus Christ, I do not want to spend the next 40 years stuck in a room. And I was lucky because a film got made of the first book, so I could see another avenue and I just jumped,” he told The Guardian in a 2015 interview. After the publication of his second book The Tesseract (1998), he returned the advance for two further novels to his publishers and soon set to work on a script about “running zombies” instead. The script? A punchy indie horror titled 28 Days Later.

Garland has spoken of the unease he felt in the literary world. “I never felt at home there,” he told a 2020 edition of the Page One Podcast. “I had a very big dose of imposter syndrome.” As a “very solitary, quite reclusive person” anyway, he felt that it would be psychologically damaging for him to be stuck in a room churning out new novels. He needed to get out more – and filmmaking was a perfect way of making new friends.

He went on to write original screenplays for films including 28 Days Later (2002) and Sunshine (2007), both of which were directed by Boyle. The former, starring the then unknown Cillian Murphy, is about a virus that causes rage in its sufferers. Garland may have been borrowing from George A Romero zombie flicks but he brought new twists to the genre – for one thing, making sure to include characters that audiences actually cared about. The film was set on desolate London streets and had a deliberately downbeat feel that led some critics to brand it zombie cinema by way of Ken Loach.

Meanwhile, Garland’s script for Sunshine, about astronauts racing against time to reignite the dying sun, came complete with classical references to the Icarus myth and a strong ecological undertow – not elements generally found in more run-of-the-mill sci-fi movies.

Despite this, there is never anything precious about the young author’s movie scripts. He took a practical approach to his new craft, likening screenplays to users’ manuals. He wrote 50 separate drafts of 28 Days Later. Working with Scottish producer Andrew Macdonald (of Trainspotting fame), Garland realised that he needed to come up with concepts that would be affordable for cash-strapped UK filmmakers. That’s why Ex Machina, for all its big ideas, was done as a chamber piece and why during the pandemic he came up with Men (2022), a deliberately small-scale horror picture set in a cosy English countryside village. For the film, Rory Kinnear gives a bravura performance – in 10 different roles.

Garland was drawn to the collaborative elements of filmmaking and ridiculed the cult of the auteur. Nonetheless, he soon started “digging his heels in” (as he put it) when directors asked for changes to his scripts. That, he said, was why he eventually stopped working with Boyle and began to call the shots himself. “For me, directing is often about not having to have a director there,” he explained. “My key bit of work is the script and then it is about having all of the team communicating with each other.”

Now, with Civil War, Garland has the biggest budget of his career and has come up with his most inflammatory idea so far. It remains to be seen how US audiences will react to a British director having the temerity to launch a new civil war in their backyard. Ahead of its release, the film has already stoking controversy, with some pundits questioning its close proximity to the forthcoming US elections.

Its star, Dunst, who plays a veteran photojournalist, said recently that making the film “shook me to my core”. She described it as “a fable of what happens when people don’t communicate with each other and stop seeing each other as human beings”.

Dunst won’t be the only one shaken: the movie is sure to generate ferocious debate from political commentators as well as movie critics. Whatever its ultimate trajectory, Civil War underlines Garland’s greatest strength as a storyteller: his ability to startle and challenge his audience – and always to get under their skin.

‘Civil War’ is released in UK cinemas on 12 April

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks