‘Black people know how scary the world is’: How Candyman became a story of radical justice

Nia DaCosta’s sequel to the 1992 horror deconstructs Candyman’s origins, digging deep into who he kills and what he wants. Adam White speaks to DaCosta and actor Nathan Stewart-Jarrett – who refused to even say the villain’s name during rehearsals

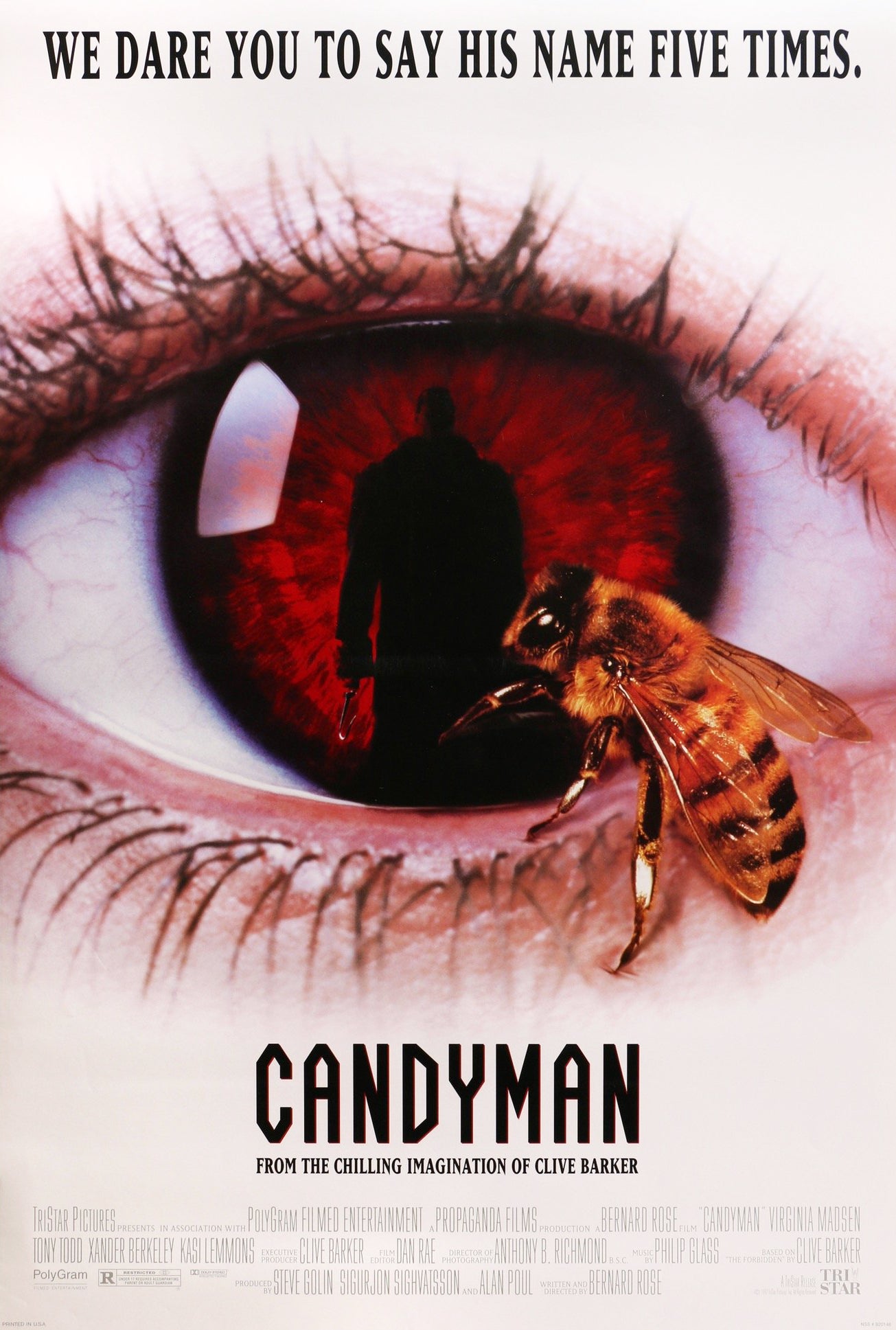

Even if you hadn’t seen Candyman, you knew not to say his name five times. In 1992, Bernard Rose’s beguiling horror masterpiece inspired collective trauma about bees, mirrors, and the haunting piano work of composer Philip Glass. Summon at your own risk the Candyman, the film told us, its message trickling out of the cinema and into the playgrounds of the world, where it spread among children far too young to actually see it. A towering, tortured and sensual spectre with a hook for a hand, Candyman would appear in the mirror and kill you if you said his name five times in a row. Nearly 30 years later, Candyman is back, just in case you might have forgotten him.

In the hands of filmmaker Nia DaCosta, the new Candyman – a direct sequel to the 1992 film – enriches the themes curdling under the surface of the original. It clears up some of the messier logic of Rose’s work, and reconfigures the Candyman himself as not just a scary figure of modern folklore, but an embodiment of generational trauma through the decades.

DaCosta, who also co-wrote the film with Oscar winner Jordan Peele (Get Out) and producer Win Rosenfeld, knew it would be a Herculean task to continue the Candyman story, particularly when the original film so successfully burrowed its way beneath our skin. But then she thought about why it affected so many people. “When I think about the horror films I grew up with, they mostly took place in the suburbs,” she recalls. “I’m thinking of films like Halloween, that usually dealt with relentless serial killers, or suburban ennui. They were things that I didn’t understand as a person living in a giant city. Candyman just felt closer to home.”

Like any urban sprawl, both films feel busy yet oppressively isolating. In Rose’s Candyman, a young graduate student (Virginia Madsen) investigates stories of a hook-handed killer (Tony Todd) slaughtering residents of Chicago’s Cabrini-Green housing project. Standing on the periphery of luxury apartment buildings, the tower block is a living monument to violence and racial inequity.

In the sequel, Cabrini-Green has been demolished and replaced by a further parade of expensive housing, and blocked artist Anthony (the ludicrously charismatic Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) selects both its tragic history and the Candyman legend to be his latest inspiration. Soon he discovers chilling links between his own upbringing and Cabrini-Green’s violent past, all the while on the fringes of a new spate of murders.

DaCosta’s direction is elegant and ambitious. There are shadow puppets, dramatic crane shots and some of the gnarliest acts of body horror on film since Natalie Portman yanked off her cuticles in Black Swan. Tougher to articulate, though, is the film’s disquieting menace. There is a phantasmagoric unease to it all, from shapes in shadows that may not even be there to human bodies that move too slowly to be ordinary.

Providing lightness amid the terror is British actor Nathan Stewart-Jarrett – of Misfits and Angels in America fame – who steals scenes as Troy, the resourceful brother of Anthony’s girlfriend Brianna (Teyonah Parris). Like DaCosta, the original Candyman left a marked impression on him as a child. Unlike DaCosta, those feelings still linger. He wouldn’t even utter the name “Candyman” during rehearsals for the film.

“I was, like: ‘Of course I’ll say it when the cameras are rolling, but I’ll just skip over it right now,’” he remembers. “I’d bleep it for myself.” He jokes – I think – that he’s even slightly uncomfortable with the amount of times I’ve said the name during questions to him. “You’re running very close to five right now!” he howls. “I just don’t f*** around with it! Like why do it? If nothing happens, then [shrugs], but if something does happen, you’d be like: Why did I say that five times?”

Stewart-Jarrett calls Troy “the smartest person in the room”, or someone who quickly recognises that he’s stuck in a horror movie. But he’s also not alone. Throughout Candyman, Black characters express rationality, keep themselves safe, and refuse to meddle with the dangerous forces their white – and doomed – counterparts take for granted. In that sense, the film reminded me of a scene in Wes Craven’s Scream 2: upon seeing the white bodies piling up around him, a Black cameraman played by actor Duane Martin calls up a taxi, gets the hell out of town and is never seen again. So when DaCosta tells me that Scream is one of her favourite movies, it comes as no surprise.

“The Black characters in my film are very much, ‘No, thank you – I don’t need to invite any more darkness into my life, I have enough to deal with in the real world,’” she says. “And it also plays into the trope of: Black people would never be in a horror movie because they would not go into the haunted house, or go camping in the haunted woods, or investigate the mysterious sound. ‘Nope, not for me – goodbye!’ But it was also acknowledging that Black people have an awareness of how scary the world is in a very specific way. We’re told about that from a young age in order to aid our survival.”

That consciousness papers over some of the cracks in Rose’s earlier vision. His film – loosely adapted from a short story by Clive Barker – gestures towards racism, inequality and the legacy of trauma. It is predominantly a mood piece, though, one that is erotic, scary and mesmerising, but also told from the limited perspective of a white character infiltrating a world that is not her own. It’s a creative choice that comes at the expense of Candyman himself, who Todd imbues with strikingly seductive menace, but whose motivations are… a bit wackadoo.

Originally alive in the 1800s, Rose’s Candyman was a Black painter, whose rise within high society was halted when he fell in love with, and impregnated, a white debutante. He was killed by racists, who sawed off his hand and slathered him in honey, leaving him for the bees. His spirit has haunted Cabrini-Green ever since, but his murderous motives are unclear throughout the film.

If he is an emblem of racism and the evils of white supremacy, why is he terrorising modern Black people? And are his efforts to turn Madsen’s character into a figure of similarly folkloric horror a kind of revenge scheme, or does he just want her as his bride? Clarity is absent. The story feels occasionally half-told, or skittish when it needed to be brave.

DaCosta’s sequel entirely deconstructs Candyman’s origins, digging deep into what he represents, who he kills and what he wants. In DaCosta’s film, Candyman isn’t so much a man as a lineage. He, and the Candymen like him, are harrowing products of American racism and distrust, the violence they impart a radical form of justice.

“Nia being at the helm of this movie really changes where the horror comes from,” Stewart-Jarrett says. “It’s no longer the horror of ‘the other’. And it kind of means that the horror is deeper. In terms of nuance, it goes back to who is driving the narrative and who’s in charge of it. Candyman was ‘the other’ in [the first film]. It’s very different now. In our film, he is definitely an antihero. He exists in a different way. He’s not just some kind of weird, shadowy monster. He’s actually this very tragic man.”

Tragic, yes, but still terrifying.

‘Candyman’ is in cinemas now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks