Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid at 50: The true story of Hollywood’s greatest outlaws

Released on 24 October 1969, ‘Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid’ wasn’t an immediate success with critics, yet it charmed the public. Martin Chilton tells the tale of one of Hollywood’s best buddy films and the two outlaws that inspired it

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The multiple Oscar-winning Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid was a groundbreaking revisionist western, with Paul Newman and Robert Redford giving a timeless portrayal of a pair of law-breaking adventurers in one of Hollywood’s greatest examples of the “buddy film”.

Although William Goldman was convinced his film script about two American outlaws who fled a posse of Pinkerton detectives and escaped to Bolivia had the potential to be a blockbuster hit, the initial response was disheartening. “Every studio but one rejected it,” Goldman recalled in The Reluctant Storyteller. “One studio head said, ‘Well, I’ll buy it if they don’t go to South America.’ I said, ‘But they went there!’ He said, ‘I don’t give a s***. All I know is John Wayne don’t run away.’”

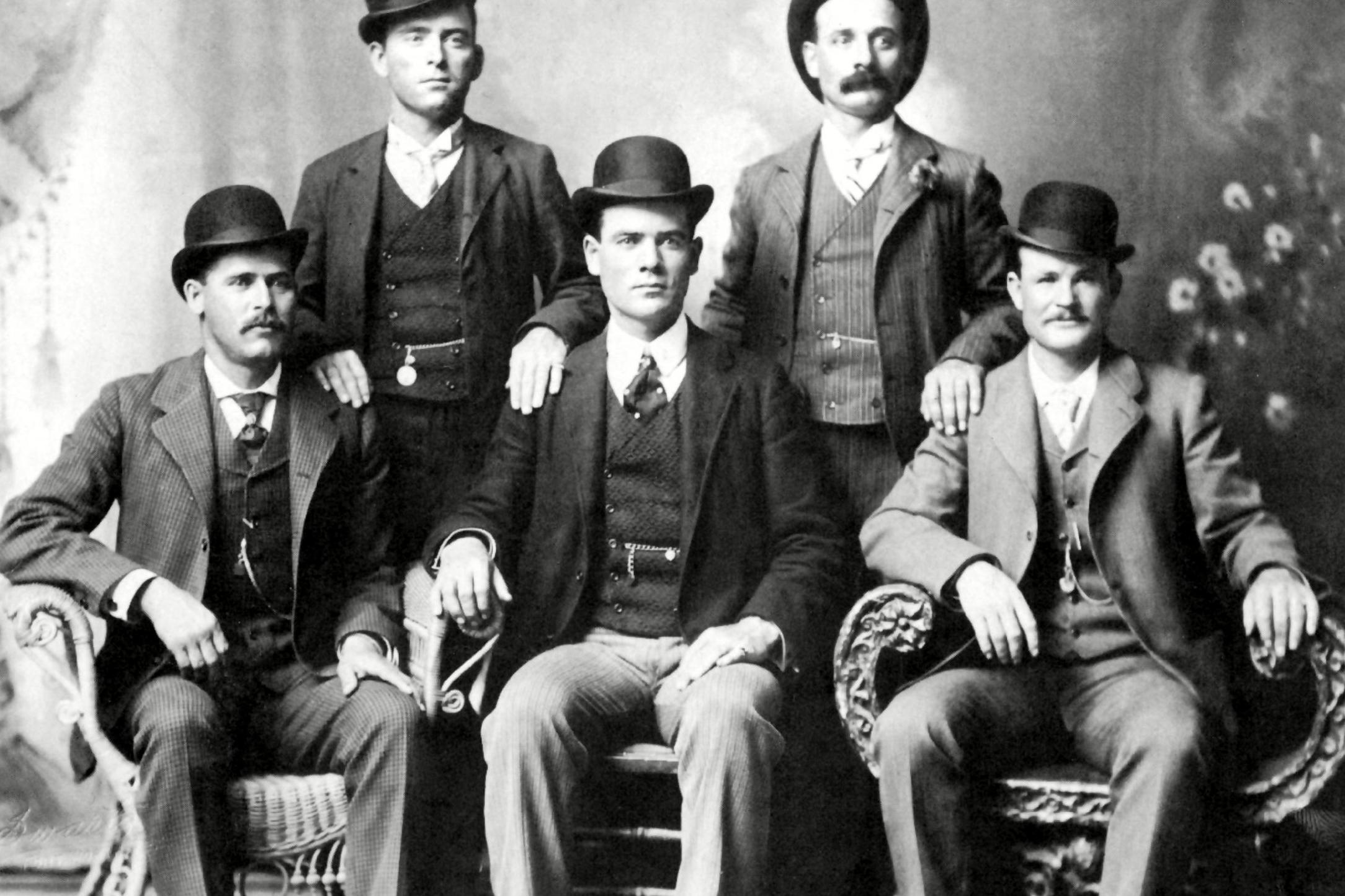

It was a difficult time to sell a story about two renegade robbers. By the late 1960s, the western was considered to be a genre in terminal decline. Novelist and playwright Goldman had been researching the true story of the outlaws Harry Longabaugh (The Sundance Kid) and Robert LeRoy Parker (Butch Cassidy) since 1959. Goldman had become so enamoured with the story of Sundance that he even used a variation of the gunslinger’s name – Harry Longbaugh – as a pseudonym for a novel.

In 1968, while working as a lecturer in creative writing at Princeton University, he finally completed his draft of the screenplay The Sundance Kid and Butch Cassidy. The ace up his sleeve was the wily literary agent Evarts Ziegler – whose clients included Joan Didion, Mario Puzo and John Cheever – who sang Goldman’s praises to Richard Zanuck, son of 20th Century Fox co-founder Darryl F Zanuck. The young Zanuck was authorised to spend $200,000 on a new script. He ended up paying $400,000 for the Sundance story, a record sum for a screenplay, equivalent to £2.8m today. “It was a brilliant piece of agenting,” said Goldman, particularly as there was no star attached to the project.

By the time Fox hired George Roy Hill as the director, Goldman’s script had been revised slightly and re-titled as Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, on the basis that Butch was being played by Paul Newman, a four-time Oscar nominee whose recent success in Cool Hand Luke confirmed his status as one of Hollywood’s leading men.

Newman was Goldman’s choice from the moment the film was bought, but the casting for Sundance was trickier. Fox initially wanted Jack Lemmon, who had appeared in a 1958 western called Cowboy along with Glenn Ford. Lemmon was not keen on spending a lot of time riding horses again and told them he was not interested. The studio then turned their attention to Steve McQueen and although he liked the script, he dropped out, reportedly in a disagreement over who got top billing.

Newman’s wife Joanne Woodward suggested 32-year-old Redford, who had appeared in a few films but was better known as a stage actor. Zanuck, who was a production manager on the film, thought Redford was too lightweight for the role and changed his mind only after seeing raw footage of Newman and Redford together and realising that they had a true chemistry on screen. “I wasn’t that well known at the time and although my agency thought I would be right for the part, 20th Century didn’t want me,” Redford told a television interviewer more than 40 years later. “They wanted Steve McQueen. But George, the director, went to the mat for me. They kept forcing him to look at other candidates but eventually they ran out of other actors.”

It seems almost ridiculous in hindsight to imagine that anyone needed to be convinced that Redford was perfect to play Sundance, the moustachioed loner with the piercing, soulful eyes. Redford was catapulted to stardom by the role, and Newman and Redford, who made only two films together – they paired up in 1973’s The Sting, but a proposed collaboration on A Walk in the Woods 35 years later did not happen – became one of Hollywood’s greatest double acts.

The pair were helped by Goldman’s script, which gave them terrific lines as witty anti-heroes. “All I ever wanted to be was a storyteller,” said Goldman, who was born in 1931 near Chicago. His own past had been tough and tragic. His mother Marion told him when he was a young boy that her deafness was the result of complications giving birth to him. When Goldman was 15, his alcoholic businessman father Maurice killed himself. His misplaced guilt over his father’s death, blaming himself for not having been around to save him, blighted his youth.

Goldman was by nature an outsider. He decided that with Butch and Sundance he wanted to flout the normal conventions of the western. Parker and Longabaugh were the leaders of the Wild Bunch – also known as the Hole in the Wall Gang – who held up banks and robbed trains in the Rocky Mountains in the 1890s. They were usually presented as grim, ruthless criminals but Goldman audaciously reinvented them for a Sixties audience, turning Butch and Sundance into lovable rogues. Their dialogue was charmingly insouciant, summed up by the following exchange:

Butch: “You know, when I was a kid, I always thought I was gonna grow up to be a hero.”

Sundance: “Well, it’s too late now.”

Butch: “What’d you say something like that for? You didn’t have to say something like that.”

Goldman acknowledged that Hill brought a dimension and depth to his script that helped create a memorable piece of cinema. It was Hill’s idea, for example, to have a bohemian love escapade scene, in which Sundance’s girlfriend, Etta Place, enjoyed a flirtatious, clowning bicycle ride with Butch. Setting the scene to BJ Thomas singing Burt Bacharach’s romantic pop song “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head” only added to the charm. Place, who was played by Katherine Ross, was a schoolteacher in the film, although Hill said she had apparently been a prostitute in real life.

Newman did the bike stunts himself – including an even more dangerous one in which he had to ride between two mules. He was luckier than one of the professional stuntmen on the movie, who fractured his pelvis after crashing from a rooftop – after being shot – and landed on wooden boxes that were too flimsy to cushion his fall. Hill was full of praise for Newman and Redford, who would come in on their days off to rehearse lines and practise action sequences. The film’s comedy is sure-footed, never too broad. During rehearsals, there was lots of discussion about whether the film was a comedy or a serious western. “You don’t play funny or sad, you play real,” Hill told his leading pair.

The behind-the-scenes tales from the production, which began on 16 September 1968, were revealing. The film has lots of explosions and the “dynamite man”, as he was known on set, had to be extremely accurate to make sure the actors and the members of the 165-strong crew were not injured. Spare a thought, though, for the bull called Bill, who was part of the bicycle scene. Bill was an extremely placid animal and the only way they could get him to charge at Newman’s stunt double was to spray the bull’s large balls with hot lotion.

The movie, much of which was filmed in Utah’s Zion National Park, was beautifully shot and another consequence of painstaking attention to detail. Hill watched 50 westerns before finally choosing cinematographer Conrad Hall, who had earned an Oscar nomination for his work on the Burt Lancaster/Lee Marvin western The Professionals. “Connie gave me that wonderful washed-out desaturated look, over-exposed with dust and smoke,” Hill said.

The film opens in sepia with newsreel footage that gives away the fate of the main characters – “the Hole in the Wall Gang, led by Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, are all dead now” reads the caption – and closes with a sepia photograph, freeze-framing their mythic deaths in a shootout with the Bolivian army in November 1908, after the pair were cornered in the dusty village of San Vicente.

It seems unbelievable, but what refuses to die is the legend that they survived the shootout with hundreds of Bolivian soldiers and actually lived on in America. “There are varying stories of their deaths in Bolivia and in fact some people in Utah, including Butch’s sister, say that Butch escaped and made it back to Utah and lived there until a few years ago under an assumed name,” said Hill in 1969. “On the other hand, most historians agree about that a whole company of Bolivian cavalry were brought in at the end to get them and it seems unlikely that either one could have survived that. In fact, I was concerned that bringing in so many men would be dramatically unbelievable, even though it was historically accurate.”

Butch Cassidy’s sister, Lula Parker Betenson, met Newman and Redford and visited the set on several occasions to watch filming. In one classic scene she witnessed, Newman defied a mutinous gang member by kicking him unexpectedly in the balls. “Is this what the movie’s going to be like?” she asked Newman afterwards. She told Newman he had captured her brother perfectly. The studio was keen to get her “onside” for promotional purposes. Redford was asked to help persuade her to attend a premiere in New Haven. “They told me to talk to her get her to say nice things about the film,” he admitted. Redford and Lula became friends and stayed in touch until her death in 1980.

According to Bill Betenson, Butch Cassidy’s biographer and great-grandnephew, the family alone knew where Cassidy was buried after his alleged “real death” in 1937. “My great-grandmother, Butch’s little sister Lula, was very clear. She said that where he was buried, and under what name, was a family secret; that he was chased all his life and now he had a chance to finally rest in peace – and that’s the way it must be,” he said in 2011.

Betenson said there were 20 well-documented sightings of Cassidy after his supposed death at 42 and claimed that when he was 59, the outlaw survivor met Lula, returning in a shiny new Ford motor car to visit his ailing father in 1925. After the shootout with the Bolivian authorities, the bodies of Butch and Sundance were identified by Carlos Pero, the courier for the Aramayo, Francke and Cia mining company. Pero had been robbed by the pair, although they had been wearing masks at the time. They were supposedly buried in an unmarked grave in a San Vicente cemetery. No photographs of the bodies were taken to provide proof.

In her 1975 memoir Butch Cassidy, My Brother, Lula Betenson claimed that a friend of the outlaw had planted the story of the death in Bolivia so that he would no longer be pursued by the Pinkertons. Butch came back and lived under an alias she said she would never disclose. She later told Welsh author Bruce Chatwin that her brother had died of pneumonia in Washington State in 1937.

In 1977, Montana author Larry Pointer caused a stir when he wrote a book claiming to prove that Cassidy had lived on as William T Phillips, who worked as a machinist in Spokane until his death in 1937, having had plastic surgery to help evade detection. To add to the confusion, this was a separate person from the man Betenson claimed had lived on until 1937.

In 2012, however, Pointer self-published a book called Butch Cassidy’s Story: Bandit Invincible in which he admitted he had got it wrong in 1977. He said he had since found compelling evidence that William T Phillips was actually a man called William T Wilcox, who had robbed banks with Cassidy in the late 19th century and knew enough inside information about the outlaw from that time to have been able to present himself as the real Cassidy.

Lawyer Anne Meadows and her husband Dan Buck also tried to solve the mystery of what really happened to the bandits in their book Digging up Butch and Sundance (1991). They interviewed other members of Cassidy’s family, who said that Lula Betenson’s book was “a pack of lies”. They hired Clyde Snow, the forensic anthropologist who identified the remains of Nazi war criminal Josef Mengele, to solve the mystery of Butch and Sundance’s final resting place. Snow received permission from Bolivian authorities to exhume two bodies. He was guided to their supposed grave by an elderly Bolivian villager who said his father had witnessed the shootout. After a comparison of DNA to the relatives of Cassidy and Longabaugh, Snow found there was no match. Instead, one of the skeletons unearthed was thought to be that of a German miner named Gustav Zimmer.

It is possible, of course, that the bodies of the famous desperados remain buried elsewhere in the San Vicente cemetery or scattered somewhere else in the town. Without conclusive proof of what happened to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, their fate remains a mystery that inspires speculation. A book in 2016 even claimed that Cassidy had lived on as a rancher in Utah until 1936 and had been buried in Duchesne City Cemetery. San Vicente is keen not to lose its claim to fame and has held celebrations re-enacting the shootout to bring in tourists.

Perhaps it is the mystery and uncertainty over what really happened that makes the ending of the film so perfect, the pair frozen in time having gone out all guns blazing at the hands of faceless soldiers. Hill described the performance of Newman and Redford in the final scene as “one of the great acting achievements” in cinema history.

When the film was released on 24 October 1969, Hill was initially nervous about the reaction to work he had so carefully crafted. “I have spent exactly a year and three months on this film, and at this point, I don’t know yet how it’s going to be received,” Hill said in the 1969 documentary The Making of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. “I think it’s a good film, I think the guys are great in it, and I think the relationships work,” added Hill. “It was a hell of a lot of hard work doing it, and actually even more fun, and if audiences don’t dig it, I think I’ll go out of my f***ing mind.”

The first signs were worrying. New Yorker critic Pauline Kael said she felt “depressed” and “rather offended” after viewing such a “facetious, empty western”. Time magazine was equally scathing, dismissing an “absurd and anachronistic” movie. The public loved the film, however. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid became the top-grossing movie of 1969, taking in more than $102m. The movie won four Academy Awards: best writing, best cinematography, best original score and best original song for “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head”. It was also nominated for best picture, best director and best sound. Bacharach won a Grammy for the score and the movie won a record nine Bafta awards in the UK.

Goldman went on to win another Oscar for his script for All the President’s Men (1976) and his memoir Adventures in the Screen Trade: A Personal View of Hollywood and Screenwriting was notable for its caustic assessment of the movie business, an industry where “nobody knows anything”. Although he continued to write popular screenplays, including for the Stephen King thriller Misery, he insisted that screenplay writing was not an art form. “If you only write screenplays, it is ultimately denigrating to the soul,” he told Publishers Weekly four years before his death in 2018. “You may get lucky and get rich, but you sure won’t get happy.”

Newman and Redford reunited with Hill when he directed the Oscar-winning 1973 movie The Sting. They retained a deep affection for the year they spent pretending to be outlaw pals. “The film was the start of a lifelong friendship and I had the most fun of any film I ever made,” said Redford. In 1981, Redford founded a non-profit organisation dedicated to the development of independent filmmakers. There was only one possible name. The Sundance Institute was born and since 1985 the associated Sundance Film Festival has helped rustle up critical recognition and acclaim for thousands of movies.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments