Burma VJ - Candid cameras

A new film on Burma, screened at Downing Street last week, shines a spotlight on tyranny and protest. Sheila Johnston reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The first film ever to be screened at No. 10 Downing Street was not an exclusive preview of the next summer blockbuster.

Its shaky, blurred, grainy images, shot with video cameras small enough to be quickly hidden at moments of danger, would not win an Oscar for Best Cinematography. And yet Burma VJ: Reporting From a Closed Country, shown last Friday at an evening hosted by Sarah Brown, is as action-packed, thrilling and suspenseful as anything at the multiplex, and vastly more moving. In fact, it is as extraordinary a spectacle as you are likely to see all year.

This remarkable film was shot by a tiny cluster of fearless young "VJs", or video journalists, operating within one of the most oppressive and secretive countries in the world, a country with virtually unparalleled official censorship (Burma is ranked 170th out of 173 countries in Reporters Without Borders' 2008 world press freedom index).

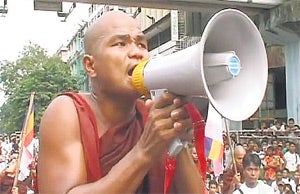

During August and September 2007, a groundswell of protest against the military junta, which has controlled Burma for decades, erupted in public demonstrations led by Buddhist monks. At least 100 were killed in the inevitable crackdown. In the absence of foreign media, the VJ's snatched camcorder images, uploaded at internet cafés or smuggled out through couriers, were the only evidence of these brutal events to seep through to the outside world. They chart a roller-coaster ride from hope, exhilaration and defiance to anxiety and ultimately, despair.

"I consider myself to be fairly well-informed, but I didn't know a thing about Burma, although it has a population of 50 million people," admits Anders Ostergaard, the Danish director who put together the footage. "Burma is a strange combination of a Third World country and a very well-organised secret-police state, and so incredibly inaccessible that, whenever anything gets out, it attracts a lot of attention. That's what got the VJ phenomenon started: the scoop quality of what these journalists were able to deliver."

Ostergaard – whose previous work includes documentaries on the Danish rock band Gasolin' and the creator of Tintin, Hergé – was in London last week to attend the Downing Street screening. The purpose of the evening was to gather support for the country's pro-democracy leader and Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi, who celebrated her 64th birthday on Friday. Ms Suu Kyi has spent 13 of the past 19 years in detention after the military junta refused to recognise the 1990 election victory of her party, the National League for Democracy. She now faces a fresh trial after giving temporary shelter to an American man who arrived uninvited at her home last month.

For Ostergaard it was "the challenge of a lifetime" to piece together Burma VJ. He was, he recalls, confronted with a pile of "raw footage shot by at least ten different people, often with no label saying where or when it was taken or by whom. Sometimes we used satellite pictures of Rangoon from Google Earth to identify the actual street corners, so that we could establish how the demonstrations developed in time. We also called in eye witnesses." It was like trying to reassemble a broken vase from hundreds of fragments. "There was," the director concludes with a touch of dry understatement, "a little bit of detective work involved."

The fragments are glued together by two devices. Staged reconstructions in the manner of Man On Wire – last year's hit documentary about the tightrope walk between the Twin Towers – give a sense of the breathless conditions under which these guerrilla film-makers worked and lived. And "Joshua", a journalist now in exile in Thailand, narrates in voice-over,

Joshua began his career aged 16 in government newspapers, but soon became disillusioned and moved to Democratic Voice of Burma, the opposition satellite television channel operating out of Oslo, for which he was one of the first recruits. He went on to co-ordinate, participate in and spearhead the VJ movement. "I have nothing on my mind," he says at one point in the film, with a touching simplicity. "I only shoot."

Ostergaard met Joshua and a number of other VJs when he travelled to Burma posing as a teacher. He says it was hard not to be overwhelmed by their bravery. "They were risking their lives to document what was going on.

"But it is important not to be too in awe of them. They felt that this was what they had to do in order to feel alive. And I wanted to say that almost anybody could be motivated in a country like this to do subversive things. Because not to do something would be unbearable."

'Burma VJ' will be released on 17 July

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments