Whatever happened to the working-class heroes of British film?

Today, acting is seen as the preserve of the posh. But in the early 1960s, British films surged with working-class talent, making gritty, funny kitchen sink dramas

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.John Lennon’s voice dripped with bitter irony when he sang that a working-class hero is something to be. In the years immediately preceding The Beatles’ peak, though, British filmgoers were familiar with such figures in a way they would never be again.

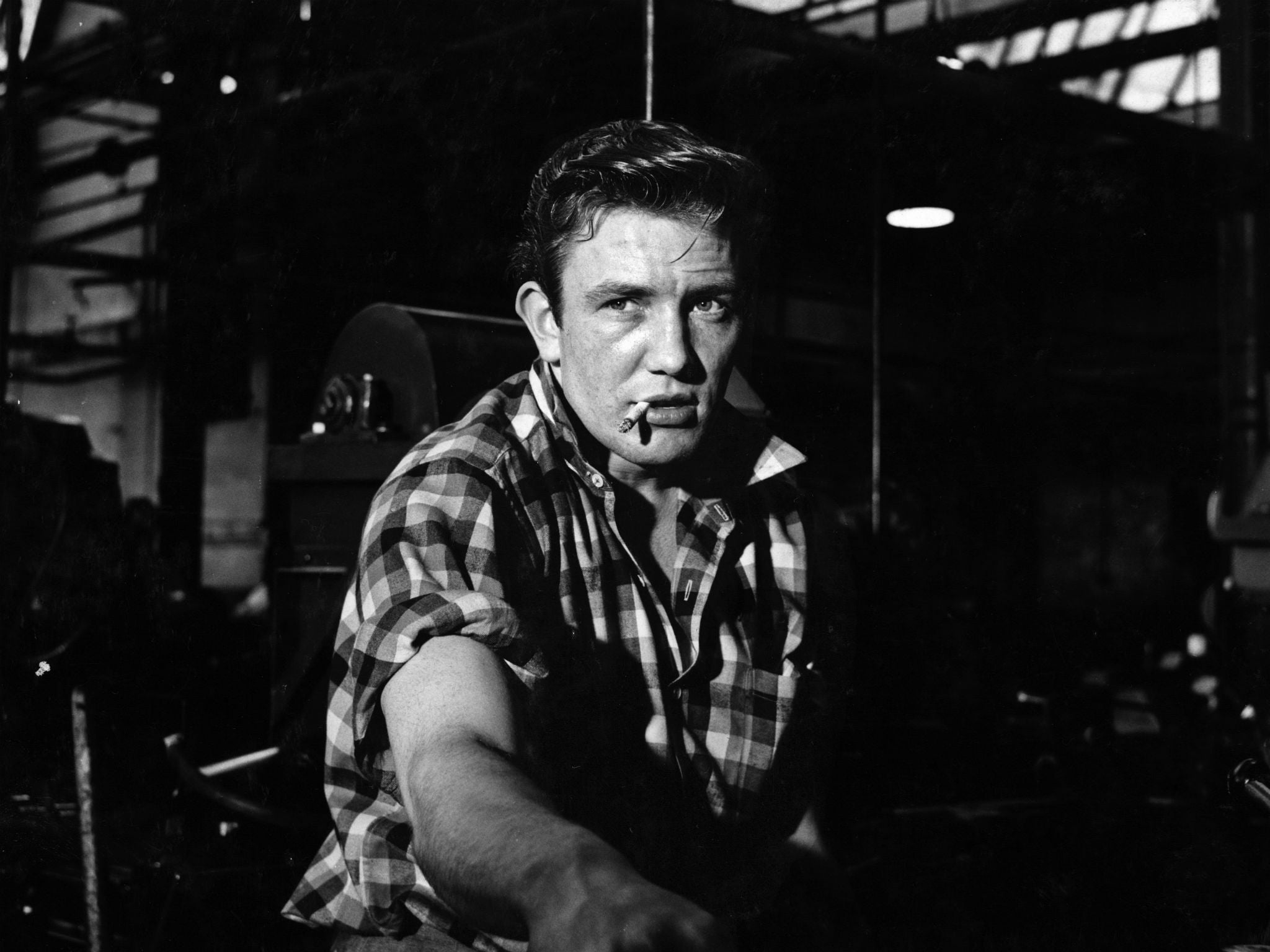

The starting-gun was fired in 1959, as Richard Burton’s bedsit-dwelling, jazz-playing misanthrope stalked through the Derby of Look Back In Anger, and Laurence Harvey destroyed himself and his lover Simone Signoret by trying to crash across the class divide in Room at the Top.

A new wave of kitchen-sink realism then introduced a generation of charismatic working-class stars: Albert Finney in Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960), Rita Tushingham in A Taste of Honey (1961), Tom Courtenay in The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962), and Richard Harris in This Sporting Life (1963).

A working-class actor or writer was certainly something to be then, in a prelude to the working-class, Beatles-led British music which lit up the world. Michael Caine and Terence Stamp became the more glamorous acting equivalents of that later, liberated surge.

This month, London’s BFI Southbank recalls this era with a season devoted to Woodfall Film, the company founded by Look Back In Anger director Tony Richardson and its original playwright John Osborne, which produced many kitchen-sink classics. The BFI will also give 14 April over to a series of screenings and discussions, entitled “Working-Class Heroes”, in which Lesley Manville, Rita Tushingham, Maxine Peake and Daniel Mays will be among those considering what has changed in the interim.

Even as Manville was Oscar-nominated for Phantom Thread this year, and one of her working-class peers from the 1980s, Gary Oldman, won Best Actor, there remains a growing suspicion that being a British film star, like being in the cabinet, requires Eton-level education.

David Morrissey and Julie Walters have decried the prohibitive expense of drama education. Benedict Cumberbatch and Tom Hiddleston meanwhile bristle at being reminded of their privileged backgrounds. But for British cinema to truly represent its people’s stories, there are still barriers to break.

Rita Tushingham, though, remembers far more formidable obstacles before she made Woodfall’s A Taste of Honey. “Woodfall wasn’t deliberately telling working-class stories,” she explains, “but John Osborne and other writers who were involved with them were writing those stories, which had never really been written before. The working-class person always had to have an accent before, was often a joker, and peripheral. At Woodfall, they were driving the film.

“People wouldn’t have gone to see them before, and people wouldn’t have financed them,” Tushingham adds of the pre-1960s social context. “Some people were snooty about it, but it built through word of mouth. Then it becomes fashionable.”

Tushingham’s fierce desire to be an actor – although “no one in my family had ever been in the business” – got her into Liverpool Repertory Theatre, before Tony Richardson offered her cinema break. The documentary-like immediacy of A Taste of Honey’s opening minutes, as Tushingham’s teenage character Jo rides a bus through rain-slicked, cobblestoned Manchester, encapsulates kitchen-sink’s landscape: almost always in the North or the East Midlands, and in bracing black-and-white.

Shelagh Delaney’s script, though, like Alan Silitoe's Nottingham stories of Saturday Night and Sunday Morning and Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, has humour which cuts through stereotypes. Jo’s pregnancy nods towards the kitchen-sink wave’s most frequent, taboo-busting rite of passage: the backstreet abortion. But Jo has a dreamy, artistic, funny nature, conveyed as much through Tushingham’s wide-eyed face as Delaney’s words, and manages to avoid this grim fate.

This role could not have existed before. Once it brought her stardom, however, she remembers class melting away for her and her peers. “When I worked with Tony [Richardson] at the Royal Court,” she recalls, “we’d go to the pub next door and there’d be Nicol Williamson and Albert [Finney], and I knew Tom Courtenay. But we never thought about our class. It was people from the outside who did.”

Courtenay was similarly dismissive of class divides in acting when I interviewed him previously . “I remember Albert [Finney] was clearing out some stuff at his mother’s,” he said, “and he found this letter praising him at the expense of Gielgud and [Ralph] Richardson, who were supposed to be old hat. Albert said reading it made him embarrassed at its stupidity. I didn’t think it was right either. It was a strange, mixed blessing for me to go to cocktail parties, mixing with middle-class people. But I didn’t want to make a life out of being working-class, or Northern.”

Still, the centrality of Courtney’s background to his work’s power is shown in the title role of Billy Liar (1963), which with its fantasising Yorkshire hero is a bridge between the kitchen-sink wave that was ending and “Swinging”, if still working-class, London. “Billy Liar was in every molecule of my body,” he told me. “In fact, there was a speech that I couldn’t get out, the feeling was so powerful. It was all about passing the 11-plus, and the money it had cost. My Dad was very aware that when I went to grammar school, it would cost him. Although he was longing for me to go.”

The importance of such viscerally convincing, autobiographical scenes is shown by the effect of kitchen-sink cinema’s last gasp, Ken Loach’s Kes (1969), on David Morrissey. “It was the first movie I saw that had people like me in it,” he once told me. “The school was like my school, and the teachers were like my teachers. The way they played football was the way we played football. And nothing was the same after that. I needed to know that the world I lived in was being represented, and was important.”

In the years since 1970, working-class talents and subject have never wholly disappeared. The searing films (though often for TV) of director Alan Clarke gave early roles to Ray Winstone (Scum) and Tim Roth (Made In Britain), and immortalised playwright Andrea Dunbar’s Bradford council estate milieu in the bawdy, bleak Rita, Sue and Bob Too (1987).

My Beautiful Launderette made a star of Daniel Day-Lewis as a (suspiciously plummy-sounding) south London skinhead, and Bob Hoskins, a resurgent Michael Caine, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach added to the broad class base of Britain’s 1980s screen revival.

Daniel Mays, the now 40-year-old star of Line of Duty, found his ambition sparked by such figures. "I remember watching Bob Hoskins in [1986’s] Mona Lisa,” he says. “It was such a fierce performance, so raw and visceral. As a younger actor starting out, you do look at films and performers you can identify with.”

More recently, Nottingham has put been back on the map, with This Is England’s auteur Shane Meadows a one-man industry, giving a fine late role to Hoskins, and early ones to Paddy Considine, Vicky McClure, and Thomas Turgoose.

Noel Clarke has drawn on his west London council estate background to become writer-director-star of the hit crime films Adulthood and Kidulthood, reaching audiences mainstream British producers hadn’t imagined. While Idris Elba has typically escaped the British double-bind of being working-class and black by working in the US (with the exception of his recent TV sitcom In the Long Run), Daniel Kaluuya at least got his break in British TV’s Skins, before his Oscar-nominated US role in Get Out. The initial career difficulty of another “Working-Class Heroes” participant, Cathy Tyson, after what should have been a star-making role in Mona Lisa, shows things were once even worse.

Flash fully forward to 2018, though, and Benedict Cumberbatch and Eddie Redmayne burn brightest, while the subtle gentrification of acting, alongside other professions from pop to journalism, seems increasingly apparent. Asked if this means the stories British cinema tells have narrowed, though, and Daniel Mays, like Courtenay before him, hesitates.

“It’s such a minefield, that question,” he considers. “If you’re perceived as a working-class actor, part of you is worried about waving the working-class flag. Part of me feels that posher actors have been celebrated more lately. But that’s just the vogue. I’m just hesitant to posh-bash; the likes of Benedict Cumberbatch and Eddie Redmayne and Tom Hollander are exceptionally gifted. We just have to make sure that other stories are still being told.

“It’s all down to the writers hunting those characters out, and having the platform to tell the stories of poorer [people],” Mays believes. “But I’ve just done Two for Joy with Billie Piper and Samantha Morton, which is a story about the underclass finding their place in the world. And Lennie James wrote and starred in Save Me on Sky Atlantic, and the council estate depicted in that felt fresh and authentic. Johnny Harris has made his boxing film [Jawbone], as has Paddy Considine [in the current release Journeyman].

"Maybe that’s a pattern," he continues, "that predominantly working-class actors need to write their own stories, in order for them to be told – like Gary Oldman’s Nil By Mouth back in the 1990s, which was so raw and real.”

If British cinema’s class divide is growing, it clearly also reflects changes in Britain. Kitchen-sink cinema grew from a more stable working-class culture, Tushingham believes.

“In the 50s and early 60s, community was incredibly important to people,” she recalls. “Look how houses were built, where everyone helped and looked out for each other. It was almost as if that was killed when they were moved into high-rises.”

Tushingham reflected on changing times at a recent screening of A Taste of Honey. “I watched with an audience of 15 to 17-year-olds,” she says, “and they were interested that this was how it was, and they felt sadness for Jo, and were touched by her simplicity. Adolescent emotions haven’t changed.”

Still, Mays sees hopeful signs, such as the ongoing, micro-budget scheme Film London Microwave, which helped his film about a day in the life of two friends reconnecting on a council estate, Shifty (2008), reach its audience. He also believes it’s crucial to have people with working-class backgrounds on the production side, “like Shaheen Baig, an imaginative casting director who is associated with working-class stories”.

Mays doesn’t necessarily blame drama schools for class shortfalls. David Morrissey, Tom Courtenay and Albert Finney all previously benefited from Rada (Morrissey told me it actually expanded his class-bound idea of what he could be), and Mays still thinks it does all it can to help those from less fortunate backgrounds.

“I had an initiative that helped me train there," he recalls. "They go above and beyond trying to find and help kids from poorer backgrounds. And they have a buddy scheme where they pair you with experienced actors with similar backgrounds, which for me was Timothy Spall. I’ve done the scheme myself since. You look for the people you identify with, and then you can hopefully be a trailblazer too.”

However challenging life may be for British working-class actors now, though, Tushingham remembers how much worse it once was.

“The business embraces far more people now. We changed that. We’ll never go back to what it was in the 1950s. I know it must be hard, thinking, ‘Oh, [actors such as Cumberbatch] can afford it.’ But there are more opportunities now, and you’ve got to fight with passion for your dream.”

The 'Working-Class Heroes' day is at the BFI Southbank on 14 April. The Woodfall Film season runs at the same venue until 30 April, and a Woodfall box-set is out on 28 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments