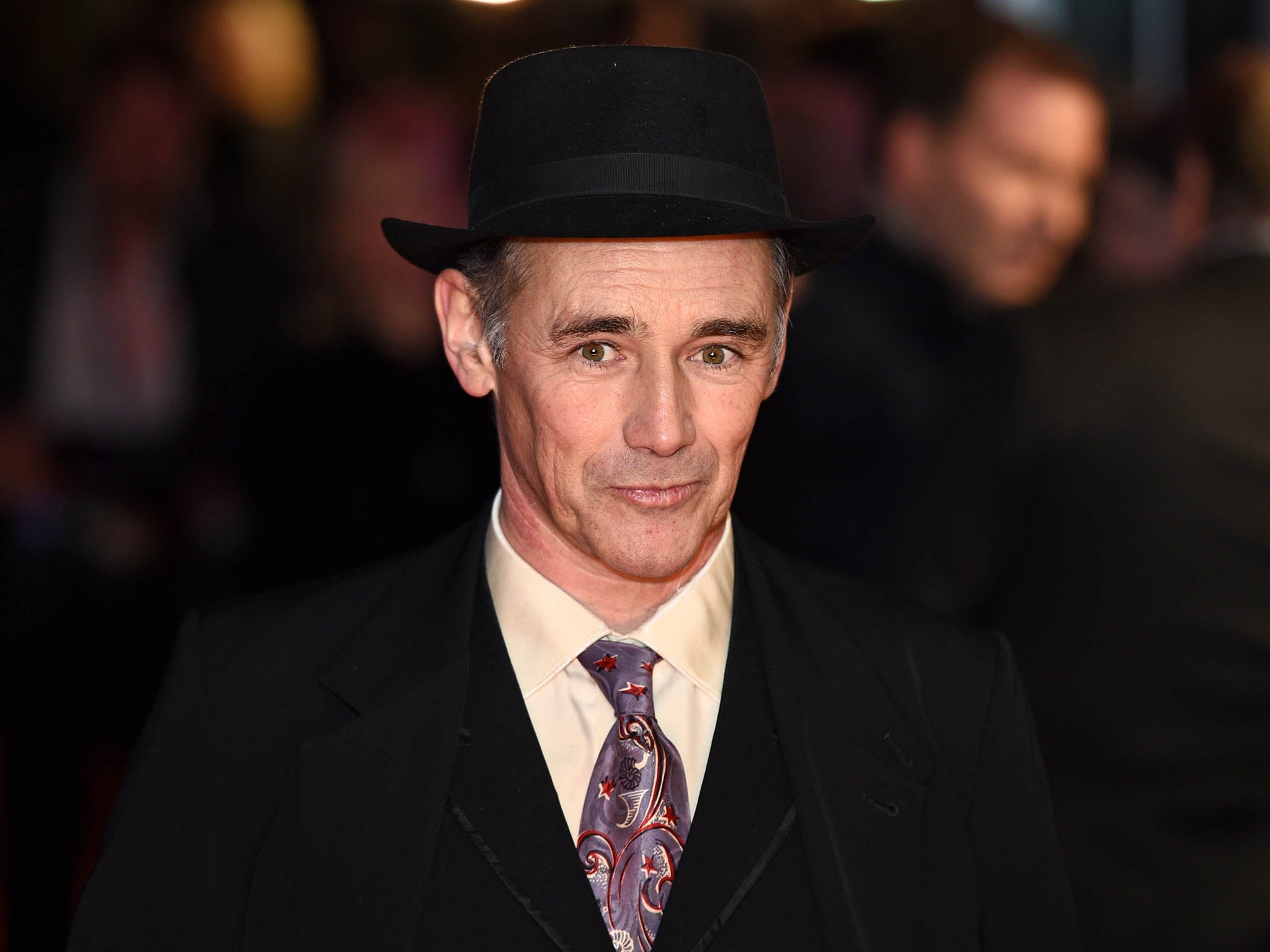

'Bridge of Spies' actor Mark Rylance talks taking on Hollywood and his relationship with Spielberg

At 55, is Mark Rylance now set for film stardom? He talks to James Mottram

In the upstairs bar of London’s Duke of York’s Theatre, Mark Rylance is deep in thought. “It’d be interesting to interview kids … to do some research,” he muses. “What are your favourite characters to play in fantasy games? Mine were characters like Spider-Man.” He absent-mindedly starts humming the old cartoon theme. Should Marvel want to reboot the franchise in the future, perhaps he could play a middle-aged version, I suggest? “The suit is too revealing,” he grins. “An older Spider-Man … we’d have to do something about the dress sense.”

Rylance in a head-to-toe unitard, spinning webs of any size? It might seem unlikely for the former artistic director of the Globe Theatre, but I’m sure he’d pull it off. He’s in a playful mood today, perhaps because we’re on his home turf: he’s been at the Duke of York’s performing Farinelli and the King, written by his wife, composer, musical director and now playwright Claire van Kampen, since it transferred from the Globe in September. I remind him that the last time we met was six months earlier at a press day for the violent Sean Penn thriller The Gunman. “That’s right, that horrible day in that hotel! That was the first time I did one of those things.”

It’s hard to believe Rylance, 55, has managed to avoid the ritual slog of the media junket until this year. Even now, because of stage commitments, he’s only doing limited press for his new film, Steven Spielberg’s impeccably crafted Cold War thriller Bridge of Spies. There’s something quite refreshing that this Rada-trained, RSC-reared actor’s acclaim has come largely through the theatre: three Tony awards – for Boeing, Boeing, the extraordinary Jerusalem and his all-male Twelfth Night (as Olivia) – barely begin to explain his magnetic power on stage.

On screen, he won a Bafta for playing weapons expert David Kelly in 2005 TV drama The Government Inspector, but films have, until now, seemed an afterthought. He did go up for roles but didn’t get them. Friends with the Coen brothers he almost scored the lead for their 2009 film, A Serious Man. “When I didn’t get the part, I was really upset,” he says. So, he took action, acquired a film agent, and won a part in 2011’s Blitz, with Jason Statham. While filming on the Old Kent Road, he remembers locals lambasting the production for its gratuitous violence. “I was ashamed to be in it. It was horrible to do.”

Rylance fired his agent. “I decided I was only going to do theatre ... I was happy being a theatre actor and this was just greediness.” But gradually, he relented. He was superb as Sir Thomas Cromwell in this year’s BBC production of Wolf Hall. Then along came Spielberg with not one but two projects. A week into shooting Bridge of Spies, the director asked Rylance to consider the lead in next year’s The BFG – a visual-effects-led take on Roald Dahl’s story.

Back in the Eighties, Spielberg offered Rylance a role in his J G Ballard adaptation, Empire of the Sun. “I took the part and then backed out,” he shrugs. “It wasn’t because of him. I was offered something in the theatre I wanted to do more.” As he revealed on Desert Island Discs earlier this year, Rylance took to the Chinese dice, the I Ching, for guidance on the matter. He’s well known for “alt-thinking” – believing in crop circles, energy fields et al. He even got married on ancient stones over the Winter Solstice.

However, there was no turning down Spielberg this time. Set in 1960, Bridge of Spies sees Rylance play the real-life Rudolf Abel, a suspected Russian spy living in a New York artistic community. Arrested, he’s used as the makeweight in an exchange with the Soviets for captured U-2 spy-plane pilot Francis Gary Powers, delicately negotiated by Tom Hanks as lawyer James B Donovan. It is co-written by the Coens and Rylance gives a beautiful performance that could well bag him his first Oscar nomination. Never perturbed by his incarceration, when Hanks’s character asks Abel why he’s not worried, he replies: “Would it help?” It’s an exchange repeated three times through the film to increasing effect, and was key to Rylance unlocking Abel. “That sense of shrugging the shoulders, that sense of nihilism ... why get worked up about this?” comments Rylance. “It feels like that’s a part of the Russian character.”

There were plentiful biographical details – not least that Abel was born in Newcastle, raised by a Scottish nanny and distributed pacifist pamphlets with his father during the Great War. “None of it was able to confirm whether he was the powerful spymaster that the Americans obviously wanted him to be, or whether he was a radio operator, which is what he claimed after he got back to Russia,” says Rylance.

Like Abel, Rylance knows something of living in America as an alien. His parents moved from Kent to the US when he was two; his father taught English. He and his two siblings spent winters there and summers in Britain, visiting their grandparents. “It made me an outsider and an insider in both places,” he says. “We were very English in America. My mother would have tea parties on the 4 July, and neither she or my father ever lost their accents.”

Rylance was a late developer, unable to speak properly until he was six. Was acting, which began in school, a way to find his voice? “Yes. Yeah. I do think that. Yeah.” He pauses. “I think it gave me – and it still gives me – a story.” We all need stories to relieve real-life pressures, he says. “My girls love watching EastEnders. I did in the early years. I would see their faces and they’d be completely relaxed.” Rylance’s “girls”, presumably, refer to his wife’s daughters, Juliet and Nataasha, from her first marriage. Nataasha died, suddenly, in 2012, of a brain haemorrhage, aged 28, causing Rylance to pull out of his starring role in the London Olympics opening ceremony.

Even the highest art can’t offer relief from such trauma. “I’m only kind of recovering my sense that what I do makes a difference,” he recently said. However, working with his wife on Farinelli and the King, playing Philippe V of Spain, has been soothing, he says. They met in 1987, while at the RSC, and shared an office for 10 years during his tenure at the Globe, where she was director of music. “We’ve both been interested in putting things together,” he says. “We call it ‘in the kitchen’ – chopping the vegetables!”

If Rylance’s time at the Globe, which ended in 2005, kept him away from the screen, he now seems in a plum position to take on Hollywood, should he want. Spielberg recently called him “one of the most extraordinary actors working anywhere”. Scratching his shoulder awkwardly, Rylance looks uncomfortable when I raise this. “He’s very, very nice to me. Very kind. I don’t understand it. I really don’t.” Is it hard to cope with such adulation? “I find it difficult,” he says, softly. “I find it raises my expectations of myself. I feel … I get embarrassed by it.” He looks troubled. “Of course a large part of me wants to believe it.”

But he looks shocked when I ask if he’d swap theatre for film. “No, I couldn’t do that. I hope not. I hope I wouldn’t lose my nerve. I know that some people who move into film lose their nerve for the stage.” With The BFG approaching, his profile is set to increase – something that’s already begun with Wolf Hall. Most who stop him on the street are gracious, he says. “There are still people, obviously, who are stopping you and want a selfie because they need to justify their own lives by being in close proximity to a celebrity ... but those are minor with me. I’m not a major celebrity.” He winks at me. “Yet.”

Bridge of Spies is in cinemas from Thursday

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks