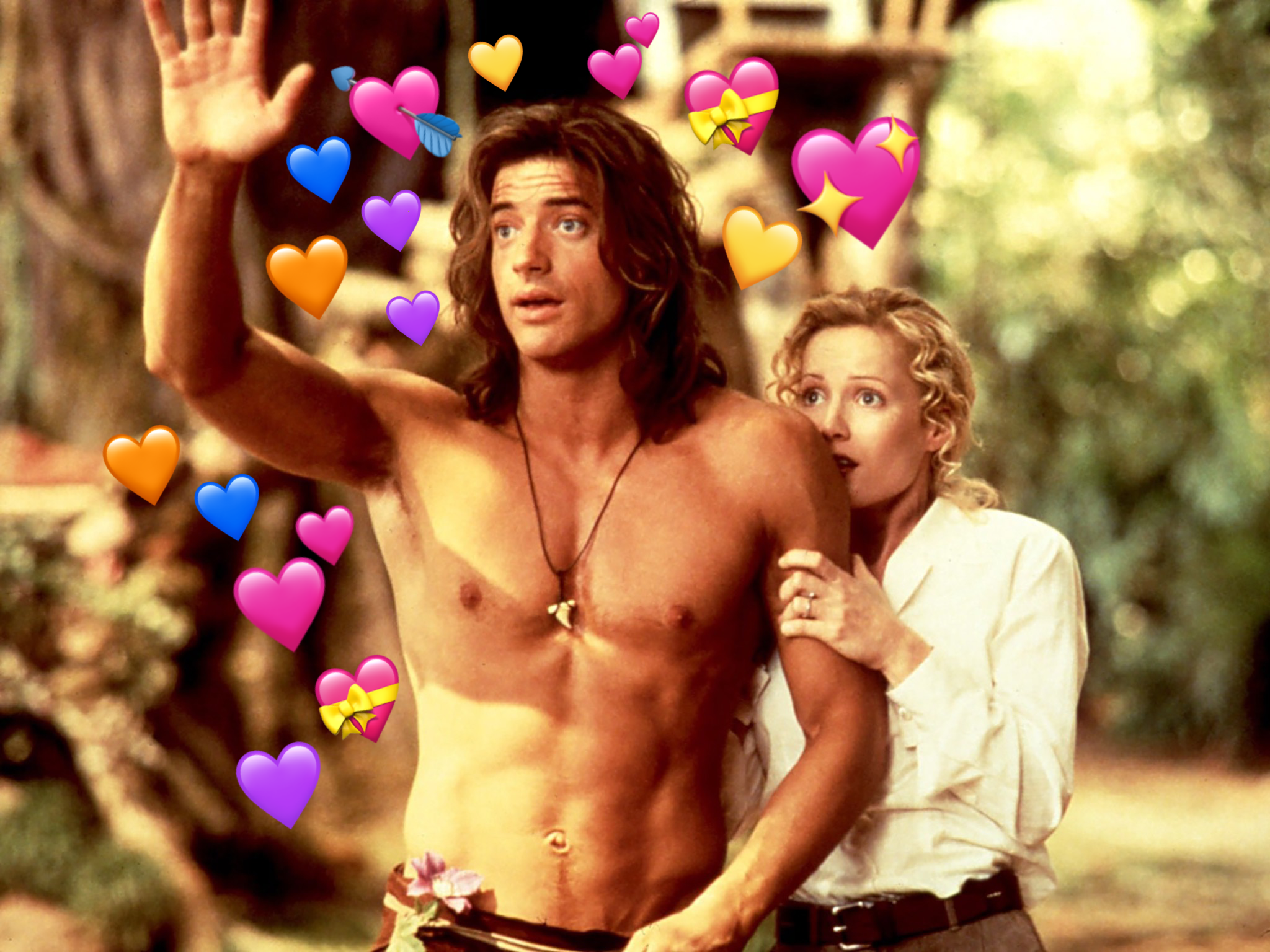

How Brendan Fraser became the internet’s favourite movie star

The beloved star of ‘George of the Jungle’ and ‘The Mummy’ has become the great unifier of the modern internet, inspiring memes, podcasts and widespread calls for a ‘Brenaissance’. As ‘The Mummy Returns’ turns 20, Adam White asks how we got here

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Has there ever been a more likeable leading man than Brendan Fraser? From 1995 until around 2003, no other movie star felt as busy or beloved. In films such as The Mummy, George of the Jungle and Looney Tunes: Back in Action, Fraser was the prototypical “himbo” – dashing and beautiful, if endearingly naive. He had charm, range and generations of fans. He also seemed to always have a movie out, right up until he suddenly didn’t.

The Mummy Returns, that most riotous of sequels, turns 20 today. Its anniversary also falls at a time when Fraser has never been more celebrated. Not because he’s as visible as he used to be or has worked on recent projects that everyone has seen. No, it’s a love lingering in a generation’s memory, then uploaded online.

Today, there are endless successions of pro-Fraser tweets, handsome archival photographs that go viral, video montages, TikToks and memes. There are Instagram accounts devoted to a potential “Brenaissance”; petitions asking Hollywood to revive his movie career; “Save Brendan” subreddits with nearly 50,000 members; and podcasts exploring the entire Fraser oeuvre. Earlier this year, the online film merch brand Super Yaki devoted a line of apparel and accessories to Fraser and his movies. “Despite the fact that he’s 6ft tall and built like a Greek statue, he always felt like a normal guy,” says Super Yaki founder Andrew Ortiz. “He felt like a friend.” If the internet is a cursed wasteland of disparate shouting, Fraser has become its great unifier.

Like many who came of age around the millennium, I never truly appreciated Fraser until he was gone. It’s the funny thing about the films that were once his bread and butter – those ebullient crowd-pleasers that cast him as rogues, oddballs and flesh-and-blood cartoons. When you’re a child, you just know that you happen to love certain movies. You don’t particularly know why. Watch his work as an adult and the specificities in his performances are clearer. Likewise, his ability to ground even the most outlandish of premises. Fraser is Han Solo meets Kermit the Frog: a leading man of shocking elasticity, who could inspire swoons, guffaws and swishy-haired thrill.

At his peak, Fraser played a lot of interlopers. In films as diverse as George of the Jungle and Encino Man, in which he’s a caveman who awakens in a teen slacker’s back garden, Fraser tended to glimpse the modern world through awe-struck eyes. He specialised in fish-out-of-water types: the young man who grew up in a nuclear bunker in the romcom Blast from the Past; the Jewish student ostracised at his white, Anglo-Saxon boarding school in School Ties; the haunted Vietnam veteran in the coming-of-age classic Now and Then. He could be swashbuckling (in The Mummy) and alluring (as the object of Ian McKellen’s affection in Gods and Monsters), frightening (as a disturbed stranger in The Passion of Darkly Noon) and hopelessly clueless (in Dudley Do-Right or Bedazzled).

Only The Mummy and George of the Jungle actually made serious money, but many others became sleepover staples. The surreal, quasi-animated Monkeybone lost 20th Century Fox $70m, but was always being discovered on Blockbuster rental shelves years after. Looney Tunes: Back in Action’s limp returns effectively killed off the franchise in 2003, but it’s only grown in popularity in the years since. Everyone who discovered movies in the Nineties, of all genders and cinematic persuasions, today has a personally formative Brendan Fraser film.

“He has this huge amount of charisma that draws you in,” says Karla Escobar, co-host of The Brendan Fraser Podcast. “In his earlier movies, especially the ones for kids, you see that he definitely relates to the children he’s working with. He gets down to the child’s level. He’s just very likeable in every movie he’s made, honestly.”

“Once every six months or so, there seems to be this sudden wave of people on Twitter posting about their favourite Brendan Fraser film,” says Escobar’s co-host Daniel Stephen. “Or people realising that they really grew up with his movies.” That often coincides, he adds, with the realisation that he’s not as “front and centre” in pop culture as he used to be.

Fraser’s vanishing act tends to be more exaggerated than it was. He has consistently worked. But around 2005, Fraser’s career began to shift. None of his family friendly studio movies, at that point already a dying breed, seemed to stick. There was Inkheart, Journey to the Centre of the Earth, Furry Vengeance and a Mummy sequel (female lead Rachel Weisz declined to return, which should have been an early sign to throw in the towel). The glossy, adult dramas Fraser was so good in, such as The Quiet American, stopped casting him. He became a Google search in human form: Whatever happened to Brendan Fraser?

In March 2018, there was finally an answer. To promote his role in the mini-series Trust, about the John Paul Getty III kidnapping, Fraser was interviewed by GQ magazine. The result is one of the greatest celebrity profiles of the past decade; a dreamy and devastating account of stardom, beauty and grief. Fraser – older, doughier and slowly peeking out from the darkness – talked about the toll his more physical kids movies took on his body. He talked about his family, his sacrifices and the disquieting timbre of fame. He also alleged that, in 2003, he was sexually assaulted by Philip Berk, the former head of the Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Berk called Fraser’s allegation “a total fabrication”.

“I became depressed,” Fraser told GQ. “I was blaming myself and I was miserable, because I was saying, ‘This is nothing; this guy reached around and he copped a feel.’ That summer wore on and I can’t remember what I went on to work on next.” He added that the alleged incident made him “retreat” and “feel reclusive”, and he lost track of who he was. Acting, he said, “withered on the vine … Something had been taken away from me.”

Stephen identifies both the GQ article and 2017’s disastrous reboot of The Mummy, starring Tom Cruise, as triggers for the internet’s Fraser resurgence. “For people who either saw that movie or didn’t see it, it was a realisation that nobody wants a Mummy movie without Brendan Fraser,” he says. “I think that was kind of a wake-up call that we miss him.”

“Especially after his [alleged] assault came to light,” adds Ortiz, “that gave people just all the more reason to want to root for him. I think when we see someone who’s been wronged, or taken advantage of in society, we want to then see them win. And I think in an absence of bigger wins, you bank a lot on these very public comeback stories.”

It helps, too, that Fraser seems to be a good’un. Modern nostalgia for the Nineties often coincides with nervous laughter at the faults of that era’s entertainment – yes, Fat Bastard in Austin Powers maybe was a dubious creation. That was Donald Trump in Home Alone 2. And, yes, Sex and the City’s Carrie Bradshaw did just compare conflict between single and married women to the Troubles. To watch culturally significant art from a different time period means having to occasionally wince at bad taste, or weather a degree of ignorance.

Fraser has no such baggage, no darker elements to his biography, no films that have aged poorly. The Mummy, in particular, has become such an oddly specific generational classic that it’s even been declared a bisexual touchstone for Gen-Y – not because anyone in the movie is literally queer, but because both Fraser and Weisz just happen to be really, really good-looking in it. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything negative about Brendan Fraser, from fans or even other celebrities,” says Escobar. “Sometimes you’ll hear things [about other stars] that they’re bad to work with or something like that. But he’s very unproblematic.”

It’s just one reason the internet seems to root for him. Arguably, it goes even deeper than that. If you were born at some point after the tail-end of the Eighties, and not into wealth or abundant opportunity, you will have faced a common kind of generational disappointment. You will have probably encountered economic instability, insecure employment, sky-high debt and increasingly expensive costs of living. You will also have a favourite Brendan Fraser movie, or owned at least one of his films on VHS as a child. To exist as a young person in 2021 is to be faced with constant inequity. Fraser’s struggles naturally strike a chord. Here is a man with enormous talent, grace and good humour, who is inherently linked to our most carefree childhood moments, and who should have had a far easier ride than he did. Seeing him flourish again would provide a degree of hope for us, too.

Later this year, Fraser will appear in two new movies: No Sudden Move, a Steven Soderbergh thriller alongside Matt Damon, Benicio Del Toro and David Harbour, and a Darren Aronofsky drama, produced by the cult indie film studio A24, called The Whale. The latter casts Fraser as an obese man attempting to reconnect with his teenage daughter. It sounds like a serious comeback vehicle, one that requires the kind of physical transformation that awards shows pay attention to. Could Brendan Fraser finally win his Oscar? An entire generation will be holding its breath.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments