Blood Simple was ‘too sleazy’ for Hollywood – but it paved the way for a whole generation of filmmakers

As Joel and Ethan Coen’s grisly noir debut turns 40, Geoffrey Macnab looks at the making of a film that influenced everyone from Quentin Tarantino to Danny Boyle

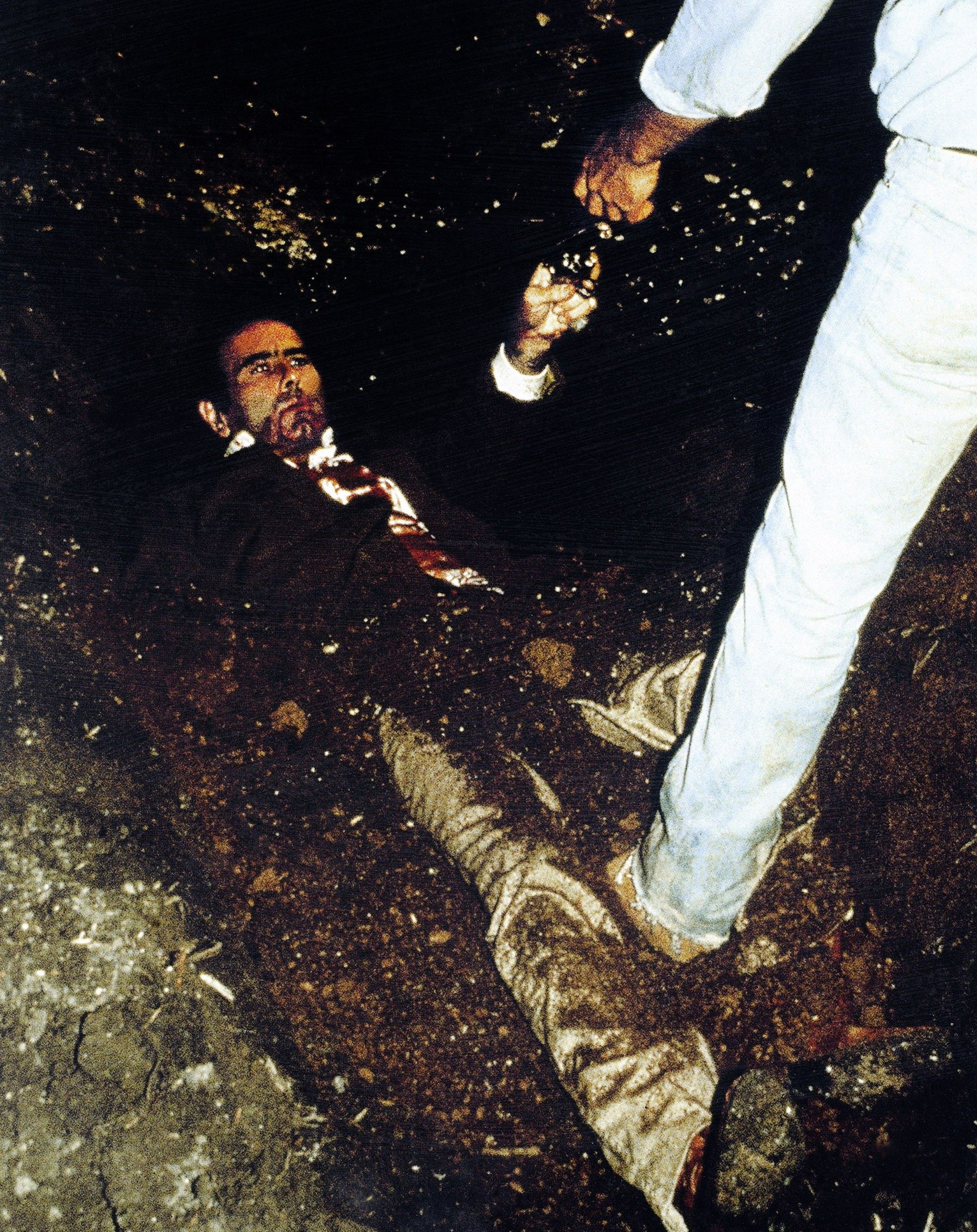

It was a cold night in Texas, and Dan Hedaya was lying in an open grave. Standing above him, shovel in hand, was John Getz. Both men were actors; they were there to film the stomach-churning “live burial” scene that marked the centrepiece of Joel and Ethan Coen’s debut feature Blood Simple. “We got to the actual grave, and Dan was in the grave, and I was digging, putting dirt on him,” Getz tells me. “He put his hand over his mouth and said ‘Throw it in my face!’”

The Coen brothers’ 1984 film was itself something of a blow to the face – and not just because of this shocking moment. Forty years on from the release of Blood Simple, its influence can be traced across cinema. Film noir had, of course, been around for a long time before the Coens gave it their own distinctly 1980s spin. You’ll find far more mud, blood and vomit here than in any of even the most nihilistic crime thrillers made from pulp novels by writers like James M Cain or Cornell Woolrich in the 1940s. The film came out in the era of the video nasties and of Sam Raimi shockers like The Evil Dead (1981), on which Joel had been an assistant editor, and shared some of their miasmatic odour.

Mainstream Hollywood had already been drawing heavily on pulp fiction traditions in movies such as Roman Polanski’s dark, tortuous Chinatown, the 1981 remake of The Postman Always Rings Twice and the Double Indemnity-inspired Body Heat. All those films, though, had a certain glossiness. By contrast, the Coens’ feature was a grungy little project, made in Austin, Texas on a very modest budget that the brothers had cobbled together themselves from a group of investors from their hometown, Minneapolis.

The Coens’ can-do attitude and morbid sensibility were a huge inspiration to other indie filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino and Danny Boyle. Both would later direct equally arresting, violent, rancid and funny movies. Would Tarantino have got away with cutting off the ear in Reservoir Dogs, or Boyle with sawing up and burying Keith Allen in Shallow Grave if the Coens hadn’t lit a path first? Would we all be watching those twisted crime series set in out-of-the-way states like Minnesota or Missouri? Probably not.

The real reason, though, that Blood Simple hasn’t dated is that human nature remains much the same today as it was in 1984. It’s a testament to the universal quality of the Coens’ tale of backstabbing, lustful, dim-witted, small-timers that Asian auteur Zhang Yimou was able to remake it in China as A Woman, a Gun and a Noodle Shop (2009) without very much being lost in translation.

This is a classic love triangle story. Frances McDormand plays Abby, the cheating wife. Getz is Ray, her barman lover, and Hedaya is Marty, the jealous husband (and also Ray’s boss at the Neon Boots strip bar). There’s a fourth major character, the redoubtable M Emmet Walsh, cast as the sleazy private detective Loren Visser. The Coens wrote the role with him in mind, little expecting he would actually take it.

Walsh’s motive for opting in was that it would be a chance to practice playing a heavy like Sydney Greenstreet (the jowly villain of The Maltese Falcon and Casablanca). “No one is ever going to hear about this film, these kids,” he later recalled thinking. He reasoned to himself that he had nothing to lose, even if he was being paid a pittance.

It turned out to be one of the highest points in Walsh’s career, which eventually stretched to over 200 films and TV appearances. His slimeball character dresses in a yellow suit, always has a film of perspiration on his brow, and drives a Volkswagen. His air of false bonhomie accentuates his ineffable creepiness.

“In Russia, they make only 50 cent a day,” he tells Marty with mock irony when he accepts $10,000 to commit a double murder. At that very moment, you see a tiny fly scuttling across his scalp.

Getz tells me that the Coens knew from the outset exactly what they were doing. “Joel was much more the director on this one. He would lay out a scene. Ethan was at his shoulder most of the time.

“We would do a take and then often the two of them would stroll away from us, talking to one another, and then they’d burst into this cackling laugh they had – and then come back having amused themselves with whatever answer they got to the problem they saw in the take.”

Getz remembers Walsh as a “curious treat” but also a bit on the cranky side, The virtuoso character actor was very tired because he had been doing a much bigger movie, Silkwood, at the same time, and he didn’t always understand what the Coens were asking of him. For example, he had no idea why the brothers wanted him to lean down and pick up his hat after he had just been stabbed in the hand, bled out and nearly killed in one of the movie’s most cartoonishly violent set-pieces.

We saw everybody from the studios to the lowliest sleaze bucket distributors in LA. And they all said no

“Just do it to amuse me,” Joel told him. “This whole goddamn movie is just to amuse you,” the irate and baffled Walsh complained.

Getz had a similar experience. “They had me trying to clean up the blood in the office with a nylon windbreaker. There was so much of it I said ‘guys, this isn’t going to absorb any of it’ but they said ‘just do it.’”

The Coens realised even if the actors didn’t that these little details – Getz forlornly mopping blood, Walsh taking time to put on his hat at a moment of maximum peril – would add immeasurably to the morbidly comic feel of the storytelling.

Blood Simple didn’t have an easy route into distribution. Once the movie was completed, the brothers travelled to Los Angeles to show it to potential buyers. “We saw everybody from the studios to the lowliest sleaze bucket distributors in LA. And they all said no,” Joel later told author Stephen Lowenstein.

“Trouble was, it was a little too arty for the sleaze studios and a little too sleazy for the majors,” Ethan explained.

The movie eventually took off primarily because of the New York and Cannes film festivals. It was watched by international critics who, in normal circumstances, might not have gone near a gruesome B-movie like this.

“Sam [Raimi] had said to me at one point that my assistant editor has this movie he’s not sure what to do with,” Stephen Woolley, founder of Palace Pictures and UK distributor of The Evil Dead, tells me. When Woolley saw the film, which Palace later released, he thought it was “fantastic”.

“I remember very well not knowing who Frances McDormand was but thinking it was an incredible performance by her…and thinking there might be a niche for this in the UK. They [the Coens] were young and they were quite unaware of the film’s possible commercial potential”

This was McDormand’s first movie. She had been recommended for the role by her roommate, Holly Hunter, and had turned up at her audition in a denim skirt and her then boyfriend’s leather jacket, which was far too big for her. (She was later to marry Joel.)

It may have been McDormand’s first movie but she still gave a strikingly original and idiosyncratic performance. Abby would traditionally have been portrayed as a Lana Turner or Barbara Stanwyck-like femme fatale but McDormand played her instead as a down-to-earth scrapper with hardly a trace of glamour or vanity about her.

Woolley met the Coens and McDormand in Cannes. “Ethan was very bookish,” he says. “Joel was very outgoing and was definitely the person who was more openly gregarious. Ethan was very quiet and was constantly reading 50s American pulp novels.”

At a time when other US indie directors such as Jim Jarmusch and David Lynch were taking inspiration from the European art house tradition, the Coens had a far more populist approach. The title of their film came from a line in Dashiell Hammett’s 1929 gumshoe novel Red Harvest. The brothers acknowledged their admiration of hardboiled American detective fiction. “I think that goes back to Chandler and Hammett and Cain. The subject matter was very grim but the tone was upbeat,” Joel explained to journalist Hal Hinson why he and Ethan sprayed Blood Simple with humour at even its darkest moments.

Another practical reason for taking on a crime thriller like this was that it was affordable, “producible on a really small budget”, just like the Sam Raimi horror films. It had four main characters and was made on location. The cinematographer Barry Sonnenfeld, who would go on to direct Men in Black, shot it in moody, shadowy fashion, just like old film noir, but it was made in colour rather than black and white because that made it easier to sell.

In recent years, the brothers have been a little disparaging of their debut movie, dismissing it to Lowenstein as “crude” and “pretty damn bad”. That’s not a verdict any fans share. To most of us, it seems like one of the true marvels of 80s cinema, a witty, dark fable that carries within it exactly the same DNA as the brothers’ later masterpieces such as Fargo (1996) and No Country for Old Men (2007).

“Stick your finger up the wrong person’s ass?” Visser inquires at one stage. It’s a question that sums up the Coens’ entire worldview in a nutshell and which, to audiences’ increasing delight, they’ve been asking in different ways ever since.

‘Blood Simple’ is available on Amazon

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks