Bill Murray doesn't care what people make him look like, as long as it's not overweight

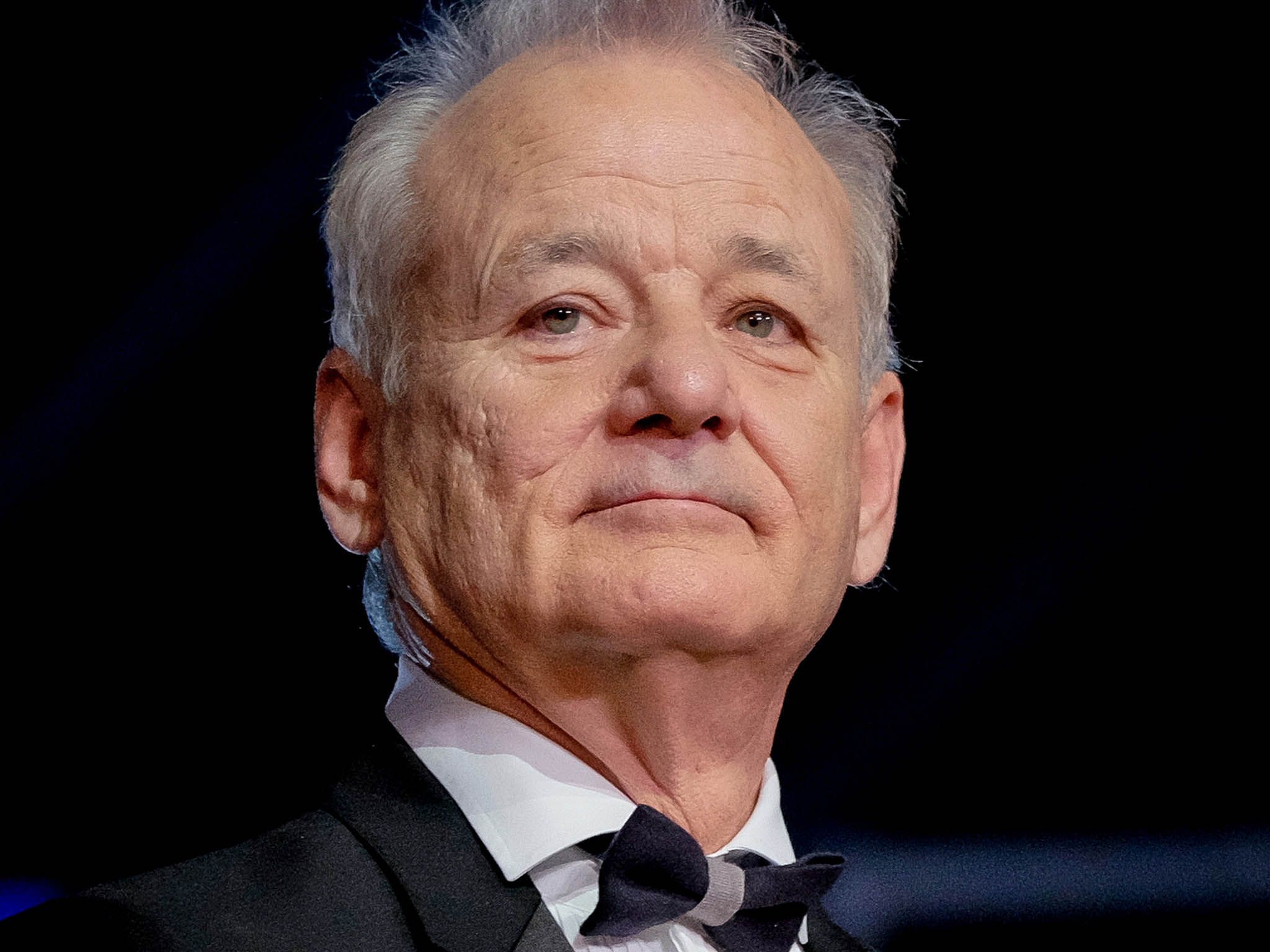

He’s a Hollywood superstar, but Bill Murray is also the bloke we’d all like to have living next door. Yet the man himself is unsure exactly who he is, he tells Kaleem Aftab

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

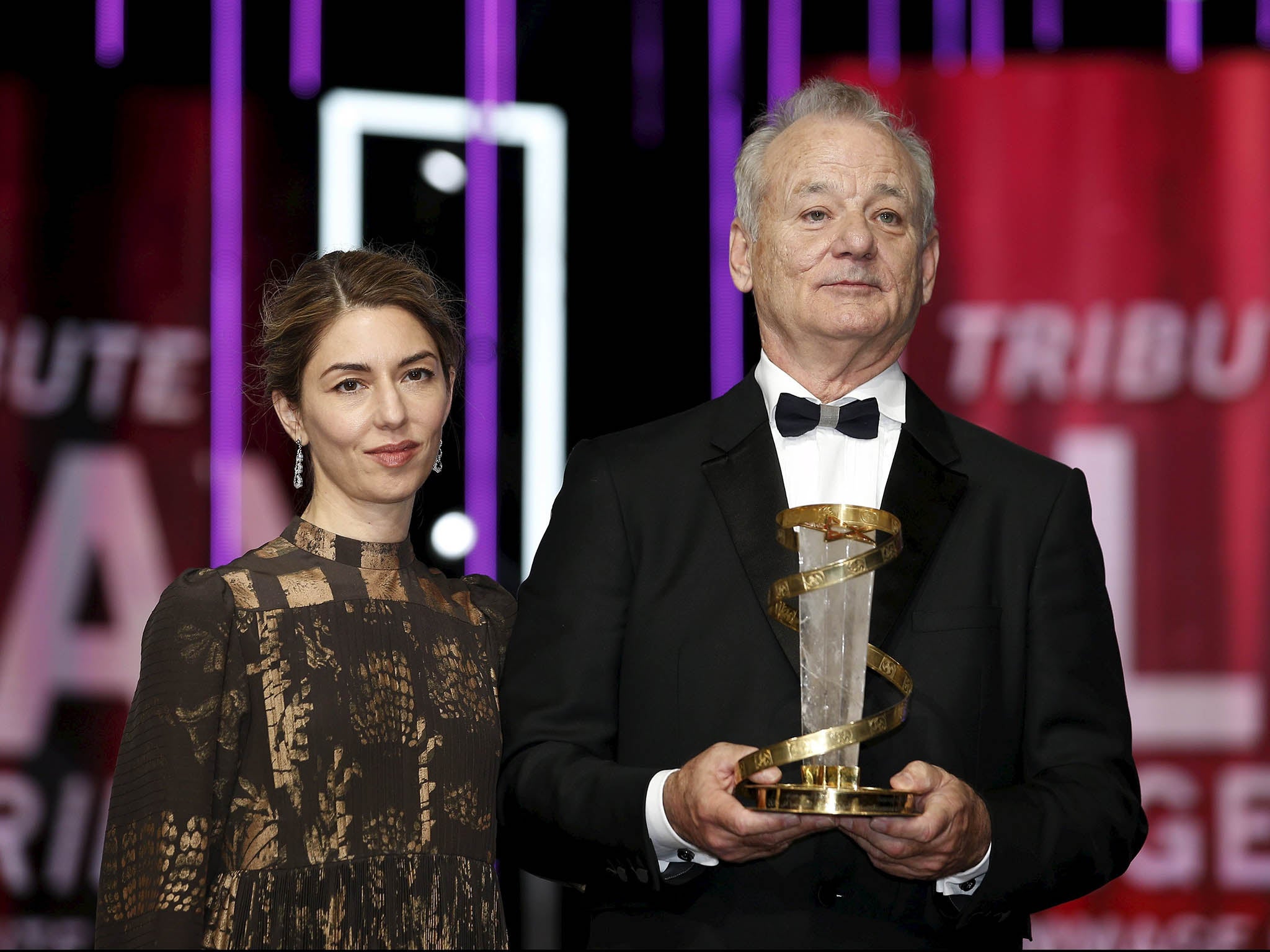

Your support makes all the difference.He famously doesn’t have a mobile phone or an agent, which makes it hard when people want to track Bill Murray down and offer him roles. “That’s not my problem,” he says at the Marrakech Film Festival, where a tribute is being paid to the actor.

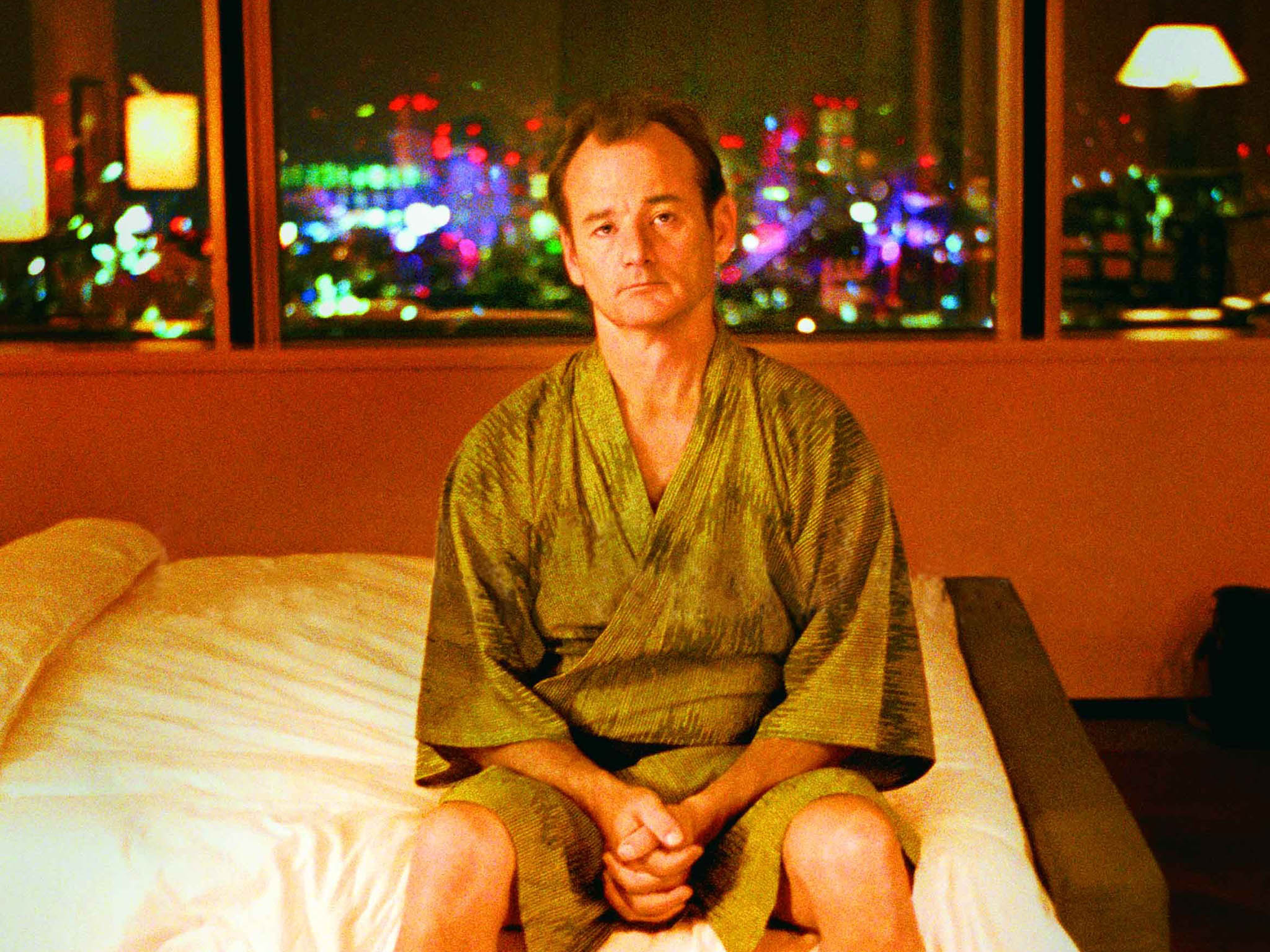

He also does not sign contracts. When Sofia Coppola was shooting Lost in Translation, Murray’s friend Mitch Glazer, who co-wrote Scrooged and has worked with the actor on his two most recent projects, the Afghan-set comedy Rock the Kasbah and the vaudeville Christmas show A Very Murray Christmas, says he got a call from Coppola, where she was trying to hide the panic in her voice: “She called me on the phone and said: ‘Mitch, how’s it going?

We shot the first 14 days of the movie, all the stuff without Bill.’ And I said, ‘isn’t he there?’ [She said,] ‘That’s what I’m calling about, have you heard from him?’”

Glazer would make an unanswered call. Two hours later Murray called Glazer from JFK airport. “Murray was saying, ‘I’m here, but do you think it will be good?’,” Glazer goes on. “When we got off the phone, my wife Kelly Lynch said, ‘is he getting on the plane?’ I said, ‘I think so’. As always when he showed up, he showed up huge.”

Coppola had already spent a year trying to convince Murray to take on the role and it’s amazing to think how close Murray came to not making Lost in Translation. The Oscar-nominated performance changed perceptions of the actor from being a very funny comedian, and a movie star with a string of hits, including Groundhog Day, Ghostbusters, and The Royal Tenenbaums, to those of an icon. He is Hollywood’s eccentric.

In Gateshead at the moment there is an exhibition by Brian Griffiths called Bill Murray: A Story of Distance, Size and Sincerity, in which the artist uses images of Murray to question the nature of celebrity. It is exciting because Murray is the epitome of cool – amazing for a man who says he chooses his clothes by whatever is on top of the laundry in the morning. Griffiths is by far the first to use the former Saturday Night Live star in this way.

Murray’s image has been appropriated for T-shirts, paintings, internet memes, cartoons, and books. I ask Murray what he feels about the exhibition and that his identity is being used in a myriad of ways. How do we know which is the real Bill Murray?

“You know, even I don’t have it right. This guy here,” he says, pointing at himself, “[is] not exactly correct about who I am. So people take it and they run with it and so long as they don’t make me look overweight, I guess that it’s OK.

There is a charm to it, you feel a little fluffed by it, oh that’s funny, you know, to create it, it’s grand, it’s fantastic. When people use creativity, I’m not going to discourage that. Like I say, it’s charming. And I don’t know, you always think that it’s going to end and a scourge will come my way, like people hunting me, like Peter Lorre, that’s what I feel can happen.”

And it’s by referencing the Hungarian-American actor Lorre, who, like Murray, could lift even the most dire movie with his mere presence, the 65-year-old actor doffs his cap to Griffiths, who has previously used Lorre in his works. But the biggest quality, and uniqueness of Murray, is not that people view him as a movie star, but that he’s one of us. An everyman.

Another instance of the legend of Murray taking on a life of its own is in the fad that grew around the belief that if you left a sign outside your house welcoming Bill Murray, he might turn up at your house-party. Like most people, Murray has crashed one or two parties in his time, but when it’s the Ghostbuster at the door, suddenly such tales become urban myths and internet memes.

If it were not for the advent of the camera-phone, I’m sure Murray would do more to add to these tales and sightings. He complains: “I used to think autographs were hard, but now I wish I could have autographs back and these phones would go away.”

At the Marrakech festival, Murray displayed the fun side that’s apparent in his characters, and in his alter-ego on A Very Murray Christmas, but most striking was his heartfelt sincerity. He mentioned recent terrorist attacks when picking up his award, but this was couched in touching comments about love for the people of Morocco, where Rock the Kasbah was shot. Then at the party afterwards, he was on the dance-floor, the centre of attention.

He and his cohorts on Saturday Night live, John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd, were famed for their adrenaline rush. Yet while Belushi burnt out, and Aykroyd faded away, Murray matured into the finest wine.

Today sharing an experience with Murray is not enough – people need to broadcast it on social media. This leads to his lament about, and aversion to, mobile phones: “Being famous is not something to complain about, because I hate it when people do.

The only really great thing about being famous is when you take your child into hospital you get attention. That is the absolute No 1 good thing about being famous, the rest of it I don’t care so much [about]. I don’t want to be paralysed by being famous, because you get a lot of attention. Like you go to the party, like last night, and it just becomes a photo-shoot.”

Despite that, he walks around in Morocco for three days with no entourage. When asked, he poses for photos. It’s a miracle of patience. When he acts this way, it’s so easy to see why he’s loved more than any other movie star. You want Murray to be your uncle. As I see Murray in different places, I’m reminded of a line in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off: “Life moves pretty fast, if you don’t stop to look around every once in a while, you might miss it.” Murray looks around.

Even so, Murray says that he’s most happy when he’s on a movie set. “I’m a much better person when I’m working on a film because I’m really committed to myself, not in a vain, prideful way, but actually being myself because I feel that film is a graphic representation of my state, whatever my state is, what I am as a person.”

This state can be seen in the contrasting ways he talks about his movies. When he chats about A Very Murray Christmas, his eyes light up. Mention Groundhog Day and there is an elation. Talking about Rock the Kasbah he is heartfelt. A Very Murray Christmas, directed by Sofia Coppola, was shot in just three days. Playing himself, “Murray” is worried that no one will come on his Christmas show when a snowstorm hits New York. “Sofia had an idea that she would like me to sing some place, like Chet Baker in a club.” In Lost in Translation, she memorably had him sing Roxy Music’s “More Than This” in a Tokyo karaoke bar. “Then Mitch Glazer said, ‘let’s do it over Christmas’.”

Murray feels he’s getting better at singing: “I’m doing The Jungle Book at the moment and I sing in that one too. I got to New Orleans with all these great musicians, and that is when I went, ‘wow’, all these things came out of me.” When he talks about himself performing, he is modest, but recognises that it would be too far to pretend that he’s anything but excellent.

Murray is also self-aware. Under his breath he adds, “yes, I made a movie from a cartoon”, as if that is a bad thing. His voice will also be used by his long-term collaborator Wes Anderson in an upcoming stop-motion film about dogs in Japan that also features the voices of Bryan Cranston and Edward Norton.

He is sketchy on giving any more than minimal details, as he is on his forthcoming role in the forthcoming all-female Ghostbusters: “I was reluctant at first, but when I was told it was an all-female cast, I thought it got around the problem of how to do another one. So I went and did one day on it. I really like those girls, I’ve worked with Melissa McCarthy before, and Kristen Wiig. Those girls are funny.”

Yet despite the partying, and the talk of fun and games, the only time I really feel that we are getting a glimpse into what makes Murray a brand is when he talks about Rock the Kasbah. Directed by Barry Levinson, the film flopped on its release in America and Britain. But Murray refused to abandon the ship. Instead the failure seems to have increased his zest to support the film. He is fiercely loyal.

When I asked Glazer to describe Murray, Glazer replied: “There is this huge, soulful, deep emotional part of him, that is so thoughtful and kind. He has shown up for me so many times in [a] crisis, the way that you would dream a friend would.”

Rock the Kasbah uses comedy to try to show that people are people, no matter their background. Murray, who studied at the Sorbonne in Paris, is concerned with how America is viewed by many people: “It may or may not be true that the American image in this lifetime is much more different than when I was a child. I think back then we were heroes of world wars and we ended the Nazis, and whatever we did we were pretty wonderful. Then those wars gave way to Vietnam, maybe even Korea, and now the grand confusion of Afghanistan and Iraq and the mess that occurred in those places.

“I don’t think Americans are sure what is going on, and the fact that we are looked upon as bullies, rather than do-gooders, is a source of great concern.”

He does not want this to come across as being unpatriotic, fully aware of how his words may be taken out of context.

“It’s not difficult to be proud to be American. I do have self-pride, not pride as in sinful, but as in self-respect. Do I respect myself as an American? Yes. Do I respect myself? Yes. Am I proud of everything I do? No. Do I respect my country? Yes. Do I respect the people? Yes. Do I respect everything we do? Nah, probably not.”

He sees movies as his way to talk about things: “I know what a failure I am in so many ways as a human, I don’t pretend to be some saviour of the world, but the ideas that I might communicate might say something.”

There is a melancholy that also pops up from time to time when he speaks. Murray lives away from the bright lights, in Charleston, South Carolina. He shares his house with his four youngest children, from his second marriage, which ended in 2008 amid accusations of adultery. He has two children from his first marriage. I have the impression that Murray, one of nine siblings himself, needs life around him. The hubbub of activity entertains him. Indeed, he says his immediate focus is family, not work.

“I have no plan, this Jungle Book is coming out. But I do realise that I have a lot of work to do on myself, and my own family. I have sort of cleared the decks for that. I don’t make plans really.”

But this is not the preamble for Murray disappearing off into the sunset. He would also like to direct again. He co-directed Quick Change in 1990, about a gang of bumbling thieves in New York, and adds: “I felt like I was going to direct movies all the time when that happened, because I liked the experience of working with actors. I can talk to actors, and have a visual eye. I would like to do another one. I can’t tell you what today, but there is a movie we would like to make.”

He enjoyed doing A Very Murray Christmas so much he would like to do it again, and Sofia Coppola is dangling a carrot in front of him. “She has been telling me now that she has been writing something and if my behaviour is good, she might ask me to do it.”

‘A Very Murray Christmas’ is on Netflix. The Marrakech Film Festival ends tomorrow. ‘Rock the Kasbah’ does not yet have a UK release date

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments