From Kubrick's Napoleon to Jodorowsky's Dune: are these the greatest films never made?

A new 800-page book is the closest thing we have to Stanley Kubrick’s ‘Napoleon’. But he was far from the only filmmaker whose most ambitious work is left to our imagination

“I expect to make the best movie ever made,” Stanley Kubrick confidently predicted in 1971. The project was Napoleon, which he would in fact fail to make at all.

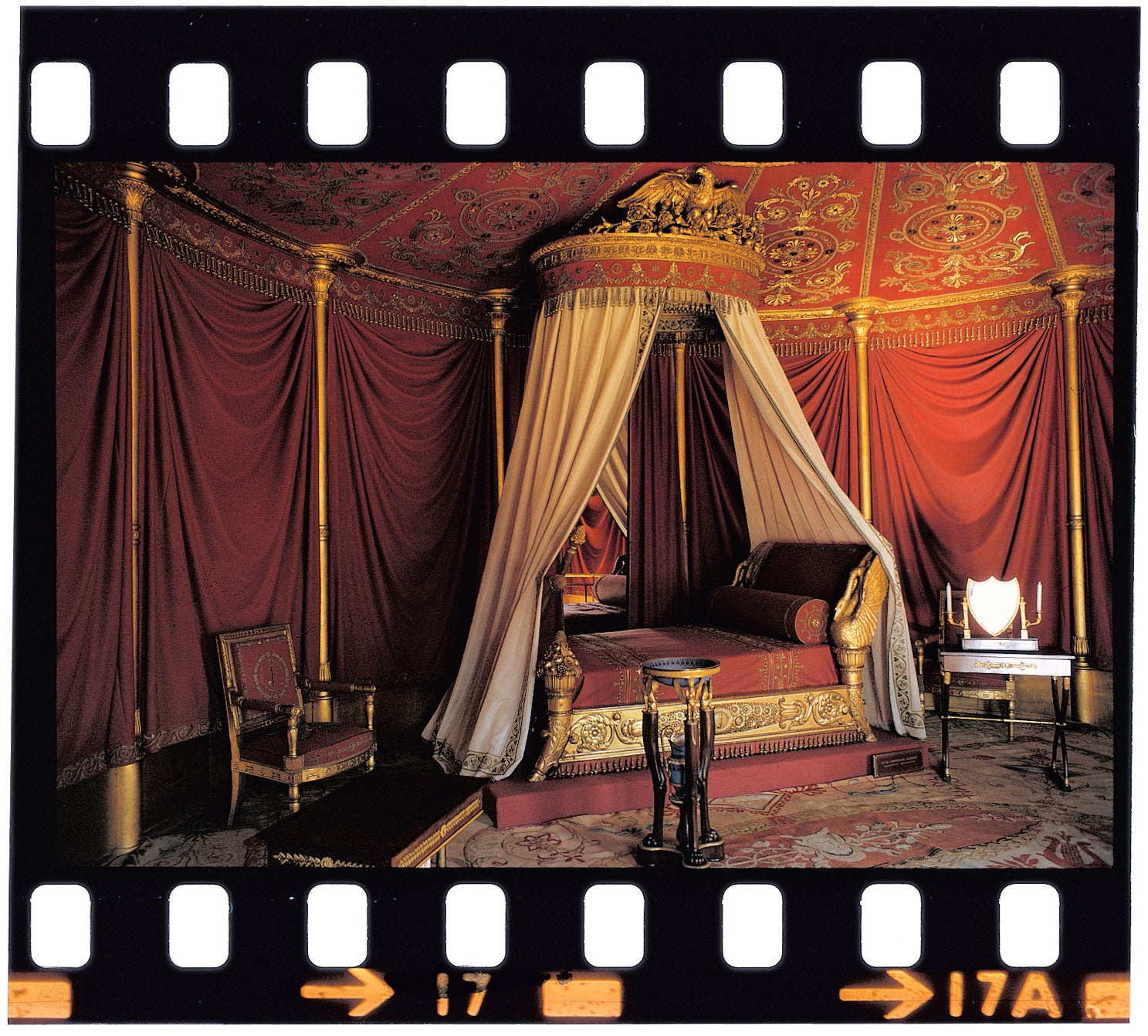

A lavish new 800-page book, Stanley Kubrick’s Napoleon: The Greatest Movie Never Made, is the next best thing. From Kubrick’s finely honed screenplay to the 17,000 painstakingly filed images he assembled from the Napoleonic era to evoke it as realistically as possible, this intended masterpiece has all its ingredients laid out.

The Kubrick film that never was starts to project in your head, the only place it will ever be seen.

Napoleon is a prominent example of cinema’s long history of unrealised dreams. Even the greatest directors have all finally been defeated by a film.

Napoleon stands out in Kubrick’s career for the huge expense and effort he put into preparing it. The book includes photos of associates in full military costume in his back garden, and some of the 15,000 colour photos taken of possible locations, from the muddy field of Waterloo to Elba. A uniformed Napoleonic soldier even stands in a Romanian studio waiting for a cinematic war Kubrick lost before it began.

After the landmark success of 2001: A Space Odyssey (in cinemas for its 50th anniversary this week), the director tried three times to follow it with Napoleon between 1968 and 1971, vacillating between actors as different as Ian Holm and Jack Nicholson for his Bonaparte.

A change in regime at MGM, and the commercial failure of the lavish epic Waterloo (1970), finally forced him towards A Clockwork Orange instead.

Kubrick had other unmade obsessions. The Aryan Papers was his Holocaust film, ready to go into production when he saw his friend Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List and gratefully abandoned a project he had found deeply depressing. “How can I ever film it?” Kubrick said of the subject.

A.I. Artificial Intelligence was delayed until digital technology allowed him to make this science-fiction Pinocchio tale, which he then wanted to produce with Spielberg directing. Spielberg demurred, but made the film after Kubrick’s death. In its dark sentiment, it is a shatteringly profound hybrid of the two men’s sensibilities.

Kubrick’s own last film, Eyes Wide Shut (1999), had been worked on since the time of Napoleon, but baffled audiences when it finally emerged.

The perfectionism seen within the pages of Kubrick’s Napoleon could be the director’s worst enemy. But this was by no means unique to Kubrick.

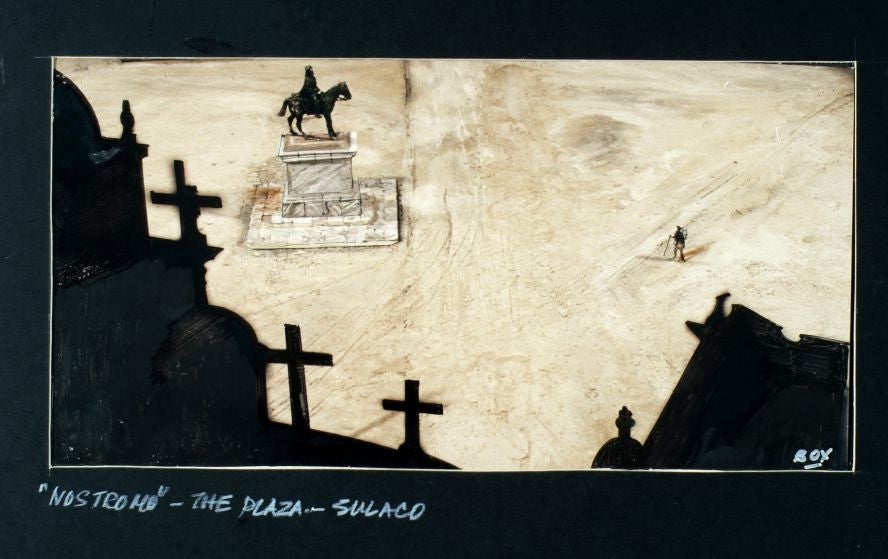

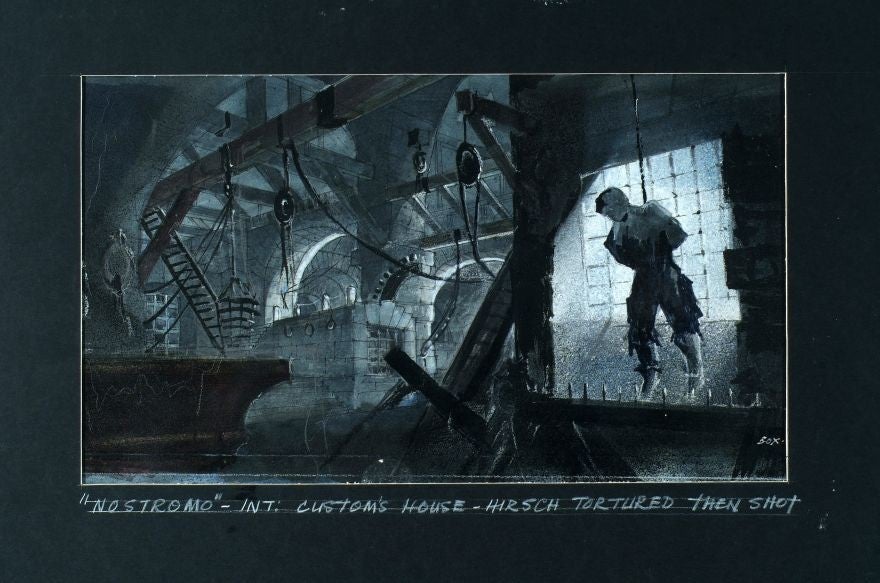

It was also the undoing of David Lean, and his efforts to make Nostromo.

A 1989 profile in the LA Times seemed to find the 81-year-old director at the height of his powers. The master filmmaker of Lawrence of Arabia and Bridge on the River Kwai had had his contemporary reputation restored by the success of A Passage to India (1984), and in 1986 he started work on an adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s Nostromo, a tale of hubris and corruption in wartorn Latin America.

Christopher Hampton and Robert Bolt were on screenwriting duties – but Nostromo took endless rewrites.

“He won’t be hurried. He won’t budge until he can smell perfection,” Katharine Hepburn wrote of him that year.

But Lean laboured too long, and the immortality he seemed to feel in 1989 was cut short by throat cancer. A flight of geese outside his window suggested death, and he intended to include their rush of wings at his hero Nostromo’s end.

His own death came first, soon after shooting was finally set to start in 1991. The script was read through once on a London stage by Christopher Eccleston, Simon Russell Beale and Irène Jacob. That apart, Lean’s last epic died with him.

Terry Gilliam has finally had better luck. After eight previous attempts to reimagine Miguel de Cervantes’s novel, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, has finally been made.

Everything short of a plague of locusts had conspired to wreck his efforts in 2000. His ageing Don Quixote, Jean Rochefort, suffered a slipped disc and hernia, jets from a nearby Nato base regularly roared overhead, and a flash-flood swept Gilliam’s equipment away.

“Quixote,” the director told reporters last year, “[is] one of those nightmares that will never leave you until you actually kill the thing.” Now, in altered form with stars Jonathan Pryce and Adam Driver, this byword for filming failure lives, and – after a lot of legal wrangling – is set to screen as the closing film for this year’s Cannes festival.

Dream projects can serve other purposes, even when they remain dreams. Alfred Hitchcock and Charlie Chaplin both spent their final years picking desultorily at projects quite beyond their capacities. The delusion that they were still filmmakers kept them alive.

In 1966, Hitchcock also fought to arrest his post-Psycho decline with a perhaps misguidedly transgressive pushing of its murderous themes. Kaleidoscope’s sympathetic protagonist was a gay bodybuilder who murders women, and contained degrees of brutality, nudity and hand-held filmed immediacy far beyond Hitchcock’s previous work.

Test stills and the screenplay exist. But perhaps for his own sake, Universal wouldn’t let their star director go so far over the edge.

Then there are films which were taken from their intended makers, leaving you to wonder what might have been. It says something for Alejandro Jodorowsky’s planned adaptation of Dune that David Lynch was the conservative choice of director.

Jodorowsky spent $2m on preparing a pipedream of a film which would have lasted 14 hours, with designers including future Alien artist HR Giger, and starring Salvador Dali, Mick Jagger and Orson Welles.

Performance director Nicolas Roeg’s year working on Flash Gordon would also surely have resulted in a far freakier, more baroque version than Mike Hodges’s camp 1980 classic.

“If not Newman, there’s Nicholson or Beatty,” Orson Welles airily told his friend Gore Vidal in 1982, over one of their waspish LA lunches. Welles was trying to secure a star for The Big Brass Ring, his screenplay about a young senator running against Reagan in 1984, who seeks out his Roosevelt-era mentor Kimball Menaker (to be played by Welles).

Stolen pearls secreted on a monkey are amongst the baroque images in a satire on the Reagan and Nixon years played out in a steamily exotic Neverland. He never made the film – although George Hickenlooper directed a heavily rewritten version of The Big Brass Ring with William Hurt in 1999.

It was “purest Welles”, Vidal said approvingly on reading the original screenplay, not least in the theme his friend described as “the devil of self-destruction that lives in every genius” – Welles’s own inescapable trait.

This characteristic made the director the great auteur of unmade films. Even his follow-up to the revolutionary dazzle of Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), can in a sense only be watched unfinished today. Welles became fatally distracted in Brazil as the studio lopped off and lost 40 minutes of his cut, excising the titular golden family’s elegiac 20th century decline. That missing fall was “the whole point”, Welles has said.

He toyed with reshooting the final scene with the surviving cast in the 1970s. This was of course wildly quixotic, a word which would have defined the decades after his final conventional great feature, 1965’s Chimes at Midnight (itself now in unviewable legal limbo), even if he hadn’t also tilted at the windmill of an unfinished Don Quixote.

The apparent tragedy of these years, scrabbling for scraps of shady finance only for his lead actor to die on him (as Laurence Harvey did, sinking late Sixties thriller The Deep) or for his funds or will to fail, left Welles picking at numerous half-made films.

His 1970s New Hollywood satire The Other Side of the Wind is still being worked on now, with Michel Legrand beginning a score in March. Jesús Franco even finished a cut of Don Quixote.

Such efforts miss the point of Welles’s last years, however, better expressed in the only film he did complete: the superbly sly mockumentary F for Fake (1974).

With no funds available from a distrustful Hollywood, he became a conjuror more than a director, preoccupying himself with the sleight of hand needed to continue making films he could never finish. Welles’s phantom filmography is, as Vidal wrote of The Big Brass Ring, “now just one more cloudy trophy to provoke one’s imagination”.

So are Kubrick’s Napoleon, Roeg’s Flash Gordon and Lean’s Nostromo. The images of what they might have been, and the grand scale of their failure, are as much a part of filmmaking as the classics they completed.

‘Stanley Kubrick’s Napoleon: The Greatest Movie Never Made’ is out now, published by Taschen. ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ is in cinemas on 18 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks