Doctors in film: Like Benedict Cumberbatch’s Doctor Strange, they’re invariably portrayed as self-obsessed and arrogant

From Marvel’s latest cinematic scalpel wielder to Jeremy Irons’ twin gynaecologists in Dead Ringers, doctors and surgeons in film don’t have a good reputation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is startling how negatively doctors are often depicted in movies. They may be performing life-saving operations and pushing back the barriers of science but, like Benedict Cumberbatch’s Doctor Strange in the early scenes of the latest Marvel blockbuster, they’re invariably portrayed as self-obsessed and very arrogant figures. From comic buffoons like James Robertson-Justice’s Sir Lancelot Spratt in British comedy Doctor In The House (1954) to the many film incarnations of Dr Henry Jekyll, they’re regarded as being out of touch with common humanity.

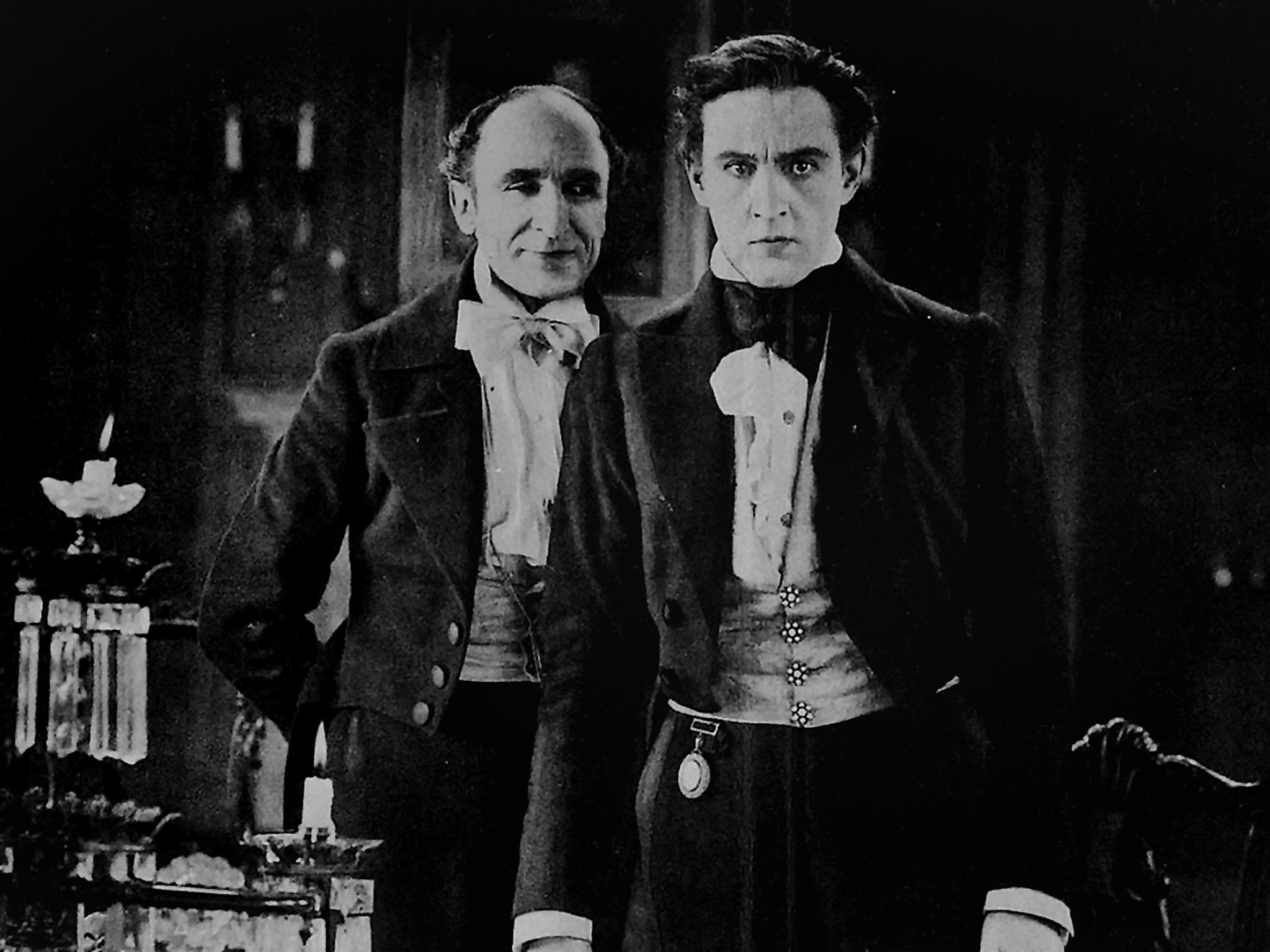

It is instructive to watch John Barrymore in one of the first screen versions of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde, made in 1920. Driven by a dangerous idealism, he is spending days and nights in the lab and is becoming ever more deranged. He just can’t stop himself from drinking the potion that turns him into Mr Hyde. As he gulps the nefarious liquid, dapper Barrymore is utterly transformed. He rolls his eyeballs, squints, grins grotesquely and suddenly develops a hunched back and vastly oversized hands which make him look like comedian Marty Feldman in Mel Brooks’ Young Frankenstein.

David Cronenberg’s movies are full of sinister doctors whose efforts to help their patients always backfire. In Shivers (1975), Dr Hobbes breeds parasite bugs to replace failing body organs. The hitch is that these parasites cause extreme lust in the bodies they enter – which means that the bugs soon spread, with maximum destructive effect. In Cronenberg’s 1977 feature Rabid, Marilyn Chambers plays a woman injured in a motorbike who has surgery which somehow results in a blood-sucking penis growing in her arm pit. In The Brood (1979), Oliver Reed plays a doctor specialising in “psychoplasmics”. His troubled patients give “birth” to cloned kids who act as a physical manifestation of their inner rage and anguish. Then there is Jeremy Irons playing the dual roles of the twins, gynaecologists who seduce the women they treat, in Dead Ringers (1988).

The doctors in Cronenberg’s films could almost be doppelgängers of the director himself. They’re experimenting and probing away at very uncomfortable subject matter which both repels and fascinates audiences. What they’re not doing is saving lives.

Even outside Cronenberg’s body horror movies, surgeons often get a bad rap. In George Miller’s Lorenzo’s Oil (1992), the doctors refused to believe there was any cure for Lorenzo Odone, the boy suffering from the tongue twisting disease, Adrenoleukodystrophy, and it was left to the parents to battle against conventional medical wisdom in their bid to keep their son alive.

“What’s the bleeding time?” Sir Lancelot Spratt famously asks the young would-be doctor Simon Sparrow (Dirk Bogarde) as he takes students through the wards in Doctor In The House, inviting them to diagnose patients. “Ten past ten,” Sparrow replies, to Spratt’s fury. The “Doctor” films rank among the more sympathetic screen portraits of the medical profession and yet they don’t inspire much confidence in the film’s protagonists. Instead of the arrogant brilliance of Cumberbatch’s Doctor Strange as he performs brain surgery, these movies celebrate bungling British amateurism. Bogarde’s Sparrow and his fellow students (played by Kenneth More, Donald Sinden and Donald Houston) aren’t anything like today’s junior doctors either. They’re “lazy, idle fellows” (there are no females among them) “always drinking, smoking and lounging”. They play golf, smoke pipes and get up to all sorts of mischief in rag week. They’re very lecherous too. “You luscious little Florence Nightingale,” Donald Sinden tries to sweet talk a nurse.

Robert Altman’s Korean War-set MASH (1970) took a similarly rollicking approach to the medical profession (albeit in a very different context). “Follow the zany antics of our combat surgeons as they cut and stitch their way along the front line, operating as bombs and bullets burst around them, snatching laughs and love between amputations and penicillin,” is the ironic message blaring from a loud speaker over the end credits of the utterly irreverent movie. Hawkeye (Donald Sutherland) and Trapper John (Elliott Gould) liked booze, sex and pranks. Their disorderly behaviour outside the operating room was matched by their professionalism within it.

Doctors in movies can be surprisingly neurotic. As the gay Jewish doctor in Sunday, Bloody Sunday (1971), pining after Murray Head, Peter Finch looked even more tormented than he had in Far From The Madding Crowd, when his love for Julie Christie went unrequited. They can also be master criminals. Long before Marvel, Fritz Lang’s uber-villain Dr Mabuse was stealing state secrets, exploiting the stock markets and using hypnosis to baffle his enemies. The character blurred completely the lines between doctor and gangster.

Horror movies and thrillers are full of sinister doctors. There are plenty of Mengele-types carrying out horrific experiments in the basement. Even when they’re combatting evil, these doctors often still remain vaguely sinister. (Think of Donald Pleasance in the Halloween movies.) Outside Doc Savage, they don’t get to be super-heroes. For some reason, they rarely get to be romantic leads on the big screen either. Omar Sharif is an obvious exception in David Lean’s epic adaptation of Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago (1965) but even he isn’t straightforwardly heroic: Zhivago is cheating on his wife (Geraldine Chaplin) with his mistress Lara (Julie Christie.)

In the early scenes of Doctor Strange, Cumberbatch fully lives up to the ideal of the surgeon as described by Spratt in Doctor In The House. “Don’t forget that to be a successful surgeon, you need the eye of a hawk, the heart of a lion and the hands of a lady,” Spratt tells the students. Doctor Strange is a virtuoso in the operating room. He’s handsome, charismatic and performs brain operations with the delicacy of a virtuoso. But he’s also obnoxious. It is only when he loses his medical career that he learns basic rules of human decency.

Why are filmmakers so distrustful of surgeons and doctors? Perhaps it’s that they see us at our most vulnerable and exposed. With their white coats, stethoscopes and scalpels, they can’t help but appear vaguely sinister. They may be there to help us but for all the life-saving operations they’ve performed in movies over the years, filmmakers and audiences still regard them with as much wariness as admiration.

‘Doctor Strange’ is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments