The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Ben Affleck: ‘It took a long time to admit to myself that I am an alcoholic’

Brooks Barnes explores Affleck’s inability to drink away his pain and the deep, personal connection in his latest role – as a washed-up alcoholic in ‘The Way Back’

Warning: this is not one of those celebrity profiles that uses a teaspoon of new information to flavour a barrel of ancient history. There is no paragraph where the star and the writer pretend to be pals – gag – while doing an everyday-person activity. What was everyone eating? Who cares. No, you will not get served the obligatory canned quote from Matt Damon.

This is Ben Affleck, raw and vulnerable, talking extensively for the first time about getting sober (again) and trying to recalibrate his career (again).

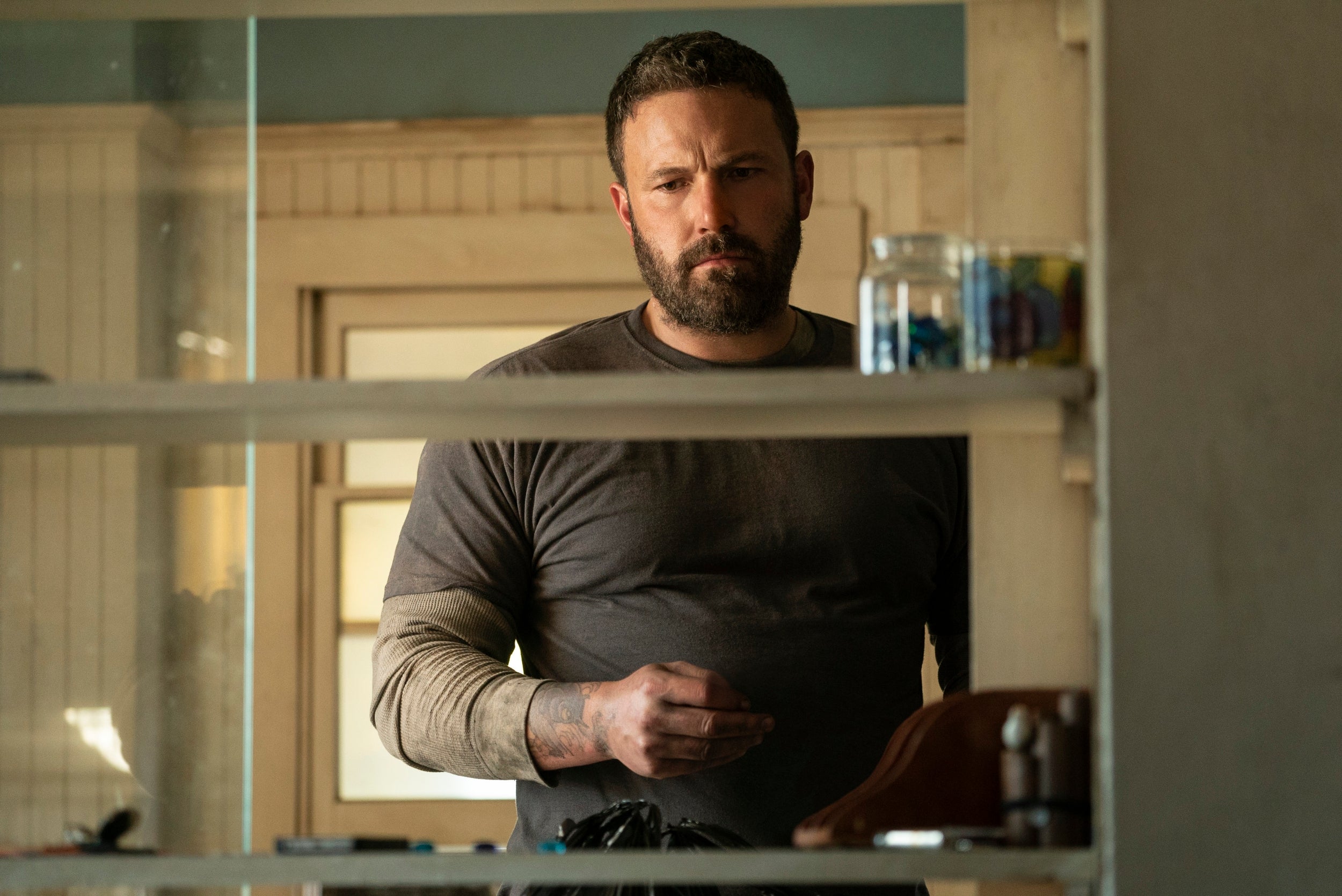

Affleck, Oscar-winning writer, director of the Oscar-winning Argo, better actor than you remember – and, yes, alcoholic, divorcee and proud possessor of a mythical back tattoo – has four movies coming out this year. Dad Bod Batman has been banished, and actual films are back on his docket, including his first all-on-him movie in four years: The Way Back, a poignant sports drama that arrives in cinemas on 6 March. Affleck plays a reluctant high school basketball coach with big problems – he’s a puffy, willful, fall-down drunk who blows up his marriage and lands in rehab.

You read that correctly.

“People with compulsive behaviour, and I am one, have this kind of basic discomfort all the time that they’re trying to make go away,” he says during a two-hour interview at a beachside spot in Los Angeles. “You’re trying to make yourself feel better with eating or drinking or sex or gambling or shopping or whatever. But that ends up making your life worse. Then you do more of it to make that discomfort go away. Then the real pain starts. It becomes a vicious cycle you can’t break. That’s at least what happened to me.”

He clears his throat. “I drank relatively normally for a long time. What happened was that I started drinking more and more when my marriage was falling apart. This was 2015, 2016. My drinking, of course, created more marital problems.”

Affleck’s marriage to Jennifer Garner, with whom he has three children, ended in 2018 after a long separation. He says he still feels guilt but has moved past shame. “The biggest regret of my life is this divorce,” he continues, noticeably using the present tense. “Shame is really toxic. There is no positive byproduct of shame. It’s just stewing in a toxic, hideous feeling of low self-worth and self-loathing.”

He takes a sharp breath and exhales slowly, as if to slow himself down. “It’s not particularly healthy for me to obsess over the failures – the relapses – and beat myself up,” he says. “I have certainly made mistakes. I have certainly done things that I regret. But you’ve got to pick yourself up, learn from it, learn some more, try to move forward.”

The Way Back was originally called The Has-Been. That downer of a title was dropped during development as the film became less focused on what a basketball talent the main character had been in high school, Affleck says. Suffice it to say, no star wants to appear on a poster next to the words The Has-Been, especially not after two box office disappointments. Justice League (2017) took in $658m (£510m), a puny sum by superhero standards, and Live by Night (2016), a period gangster drama that he also directed, flatlined with $23m.

I have certainly made mistakes. I have certainly done things that I regret. But you’ve got to pick yourself up, learn from it, learn some more, try to move forward

Affleck, 47, has been working like a madman to get his career back on track. The hard truth is that the outcome is not guaranteed. Moviegoers, women in particular, will ultimately decide: Is forgiveness for transgressions still something that society in all of its Twitter-fied polarisation allows? To some, Affleck is still the guy who broke Garner’s heart and who was accused of groping a talk-show host in 2013. “I acted inappropriately,” he says of that incident in 2017, as the #MeToo era dawned, “and I sincerely apologise.”

Hollywood has certainly granted Affleck clemency. He just finished acting in Deep Water, a psychological thriller co-starring Ana de Armas (Knives Out) that’s due in cinemas in November. He’s on Netflix this month in The Last Thing He Wanted, an abysmally reviewed mystery anchored by Anne Hathaway and directed by Dee Rees. Affleck has also been working with the Oscar-nominated Nicole Holofcener (Can You Ever Forgive Me?) and Damon on the script for The Last Duel, which begins filming in France this month. Set in the 14th century, The Last Duel re-teams Affleck and Damon as screenwriters for the first time since Good Will Hunting in 1997; Ridley Scott is directing the film, which has Oscar bait written all over it. Disney plans to release The Last Duel in cinemas at Christmas through its 20th Century label.

Affleck is also zeroing in on another directing project for himself. It probably won’t be that previously announced remake of the 1957 drama Witness for the Prosecution, he says. Instead, he wants to tackle King Leopold’s Ghost, an epic about the colonial plundering of what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo; Martin Scorsese has signed on as a producer. (Affleck co-founded the Eastern Congo Initiative, a nonprofit advocacy group, in 2010.)

Africa in 1900 is a long way from The Batman, which Affleck was supposed to direct himself. He stepped aside, allowing Matt Reeves to take over (and Robert Pattinson to don the cowl), after deciding that the troubled shoot for Justice League had sapped his interest. Affleck never seemed to enjoy his time as Batman; his sullen demeanour while promoting Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice in 2016 resulted in the hit meme Sad Affleck. “I showed somebody the Batman script,” Affleck recalls. “They said, ‘I think the script is good. I also think you’ll drink yourself to death if you go through what you just went through again.’”

He has not talked much about his alcoholism since completing a third stint in rehab in 2018. (The first two were in 2001 and 2017.) But the arrival of The Way Back has made the subject impossible to avoid. Affleck has also accepted that the second word in Alcoholics Anonymous does not apply to him – certainly not after he (briefly) relapsed in autumn, turning up smashed on TMZ a few months after making it known that he had achieved one year of continuous sobriety.

“Relapse is embarrassing, obviously,” he says. “I wish it didn’t happen. I really wish it wasn’t on the internet for my kids to see. Jen and I did our best to address it and be honest.”

Growing up in Massachusetts, Affleck saw his own father drunk almost every day, he says. “My dad didn’t really get sober until I was 19,” Affleck says, becoming guarded all of a sudden. (It was one of only two times when he chose each word carefully, with the other being his answer to a question about Harvey Weinstein’s trial on charges of rape and sexual assault. Early in his career, Affleck starred in multiple movies that were backed by Weinstein’s companies. “I don’t know that I have anything to really add or say that hasn’t been said already and better by people who have been personally victimised or who are survivors of what he did,” he says. Three years ago, Affleck announced that he would donate all future residual payments from Weinstein films to anti-sexual assault charities.)

“The older I’ve gotten, the more I recognise that my dad did the best he could,” Affleck says. “There’s a lot of alcoholism and mental illness in my family. The legacy of that is quite powerful and sometimes hard to shake.” Affleck’s younger brother, Casey, 44, has spoken about his own alcoholism and sobriety. Their paternal grandmother took her own life in a motel when she was 46. An uncle killed himself with a shotgun. An aunt was a heroin addict.

“It took me a long time to fundamentally, deeply, without a hint of doubt, admit to myself that I am an alcoholic,” Ben Affleck says. “The next drink will not be different.”

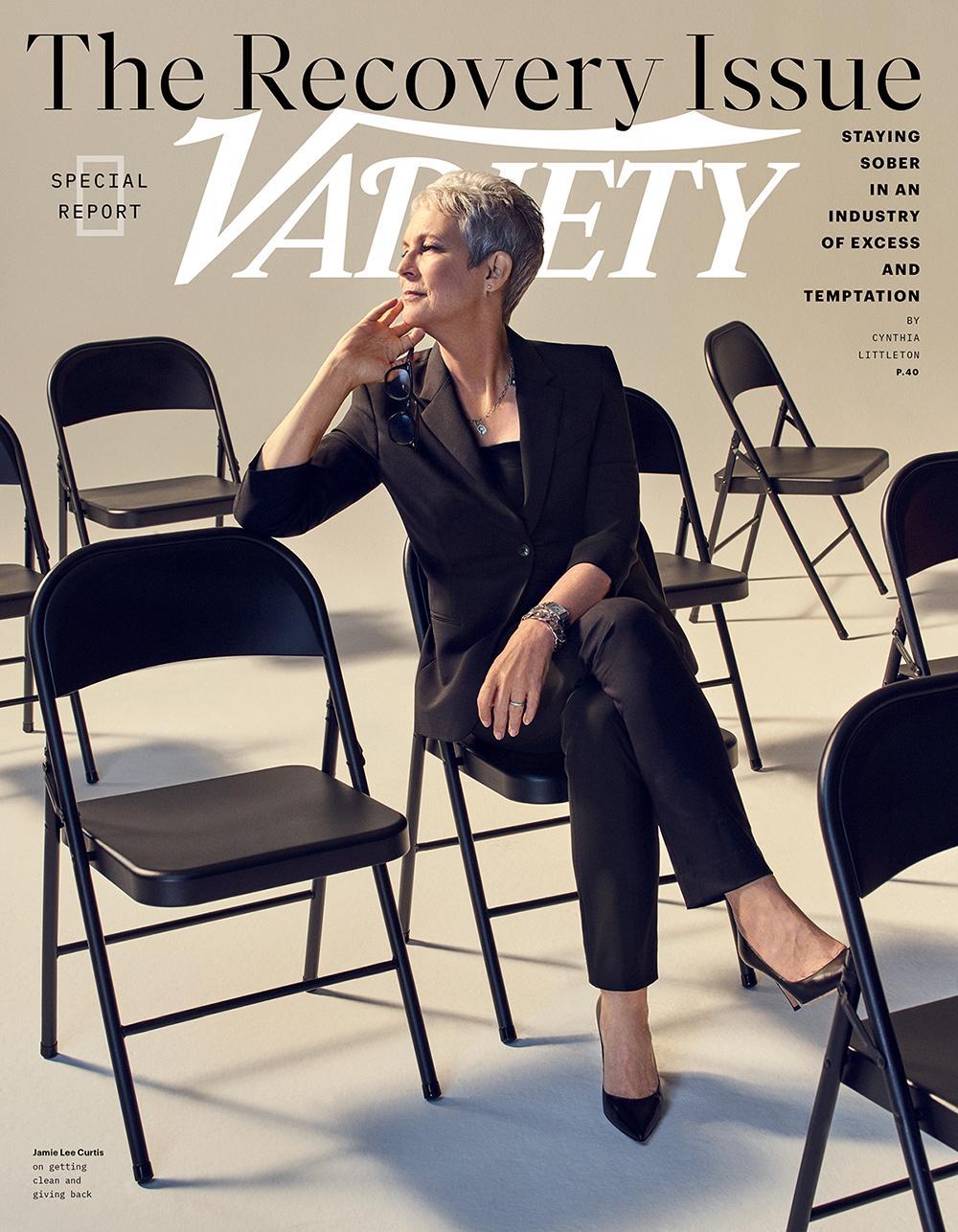

It seemed like a good moment to point out how many stars had started to speak out about getting sober – Brad Pitt most notably – and how that was lessening the stigma of addiction and, perhaps, inspiring people with substance problems to seek help. Jamie Lee Curtis, sober for two decades, appeared on the cover of Variety’s “recovery” issue in November. Discussing their sobriety in recent books and interviews have been Demi Lovato, Anthony Hopkins, Jessica Simpson, Demi Moore and, of course, Elton John, who has sponsored Eminem.

Affleck cites the sober A-listers Bradley Cooper and Robert Downey Jr. as “guys who have been very supportive and to whom I feel a great sense of gratitude”. Affleck continues. “One of the things about recovery that I think people sometimes overlook is the fact that it inculcates certain values. Be honest. Be accountable. Help other people. Apologise when you’re wrong.”

It took me a long time to fundamentally, deeply, without a hint of doubt, admit to myself that I am an alcoholic

Honesty. Hmm.

Let’s talk about honesty for a minute. Shouldn’t he have been honest from the start about the damn back tattoo rather than telling Extra it was “fake” for a movie?

“I resented that somebody got a picture of it by spying on me,” Affleck says, shifting on the sofa where he was sitting. “It felt invasive. But you’re right. I could have said, ‘That’s none of your business.’ I guess I got a kick out of messing with Extra. Is your tattoo real or not real? Of course, it’s real! No, I put a fake tattoo on my back and then hid it.”

For the record, it’s not nearly as garish in person.

Affleck has a habit of putting himself in the crosshairs. He thought it was a good idea to star (with Damon) as a fallen angel in Kevin Smith’s Dogma (1999), which Disney decided was too blasphemous for its Miramax label to release. Playing Batman as melancholy and middle-aged was certainly not the safe choice. The Last Duel has already provoked indignation on social media; Affleck and Damon play a knight and a squire who are forced to duel after a woman’s rape accusation.

And now comes The Way Back, a spare film with a 1970s vibe about a man imprisoned by alcoholism.

How exactly does he make these choices?

Affleck laughs. “I’ve never been very risk-averse – for better or worse, obviously,” he says. “Regarding The Way Back, the benefits, to me, far outweighed the risks. I found it very therapeutic.”

The Way Back was directed by Gavin O’Connor (The Accountant, also starring Affleck and a surprise hit) from a script by O’Connor and Brad Ingelsby (Out of the Furnace). It cost Warner Bros and Bron Studios about $25m to make and was primarily shot in San Pedro, a working-class area of Los Angeles.

“I think that Ben, in an artistic way, in a deeply human way, wanted to confront his own issues through this character and heal,” O’Connor says by phone.

Jack Cunningham (Affleck) is a construction worker coping with devastating personal loss. His home away from home is a lowlife bar, the kind of place you can smell before you go in. Sometimes he holes up in his apartment to down cases of beer. He starts each morning by drinking beer in the shower, the can be balanced on a sad soap caddy.

Without knowing the extent of his alcoholism, the principal at Jack’s alma mater asks him to coach the boys basketball team, which has even less self-esteem than he does. Melvin Gregg (American Vandal) stars as a player with off-court troubles.

“The hardest part of the movie for Ben was really the basketball,” O’Connor says. “If you’ve never really played before, being on a court is like, you know, being on ice skates for the first time. Once that part clicked, we were cooking with gasoline. He was already ready to go to really deep, dark places with the drinking.”

Michaela Watkins (Casual) plays Jack’s worried sister. In one memorable scene, he sits in her kitchen pretending to be fine – fine. When she challenges him, he explodes. “Out of nowhere in one take, Ben backhanded the beer can sitting in front of him,” Watkins says by phone. “It was immediate, and it was scary and it was exactly the right instinct. He was a powder keg, and she had no idea that she had lit it.”

Affleck talks about that moment, too.

“She’s pressing to see if he’s OK, and I know how uncomfortable that can be for an alcoholic – when you have that nagging, irritating, suspicious feeling that the person is right but you don’t want to admit it. Smacking the can was my version of backed-into-a-corner, primal level of denial, the way our minds hold onto these addictions in a reptilian way.”

Towards the end of The Way Back (spoiler alert), Jack has a powerful interaction with his ex-wife (Janina Gavankar, The Morning Show). He is in rehab at this point, and, when she comes to see how he is doing, he offers her an unflinching apology.

“I failed you,” he says. “I failed our marriage.”

It’s rough stuff, especially when watched through the prism of everything that has gone on with Affleck off-screen. You can’t help but think about similar conversations that he must have had with Garner.

“It was really important, without being mawkish or false, that he make amends to her – that he take accountability for the pain that he and only he has caused,” Affleck says.

O’Connor says Affleck had a “total breakdown” on set after completing the scene.

“It was like a floodgate opened up,” the director says. “It was startling and powerful. I think that was a very personal moment in the movie. I think that was him.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks