‘Holy rubber nipples, Batman!’: How on earth did the Dark Knight survive Batman & Robin?

The notorious 1997 sequel nearly has it all: ice puns, codpieces, Uma Thurman as a drag queen from hell. What it doesn’t have are fans. As ‘Batman & Robin’ turns 25, Tom Fordy dives inside the making of one of the most misfiring superhero movies in history

Ask bat-fans to name the greatest ever Batman movie and they’re spoilt for choice. Ask them to name the worst and the answer is unanimous: Batman & Robin. The notorious 1997 sequel is Batman on ice – literally – and thin ice at that. In its first 10 minutes, our titular heroes have put their actual skates on, been rocketed out of the planet’s atmosphere, and surfed back down to Earth – at which point Arnold Schwarzenegger’s sub-zero supervillain Mr Freeze zaps Robin into a block of ice. But fear not, as Batman’s got a special de-icing gadget for such an eventuality. Phew!

Producer Michael E Uslan remembers what happened when he read the script for Batman & Robin – he threw it across the room. “Our head of development, FJ DeSanto, was just coming back from lunch,” recalls Uslan. “As he walked into the office, the script whizzed by his head – about an inch away – and hit the wall. The little holder broke apart and the pages went flying around the office.”

Uslan – the long-time executive producer of the Batman franchise – sent letters, emails, and notes to Warner Bros about the film’s creative direction. “Rationalising, explaining, debating, cajoling, prying,” he says. His letters, emails, and notes filled three whole filing cabinets. “In retrospect, I probably sounded like that annoying kid you can’t shake off your ankle.”

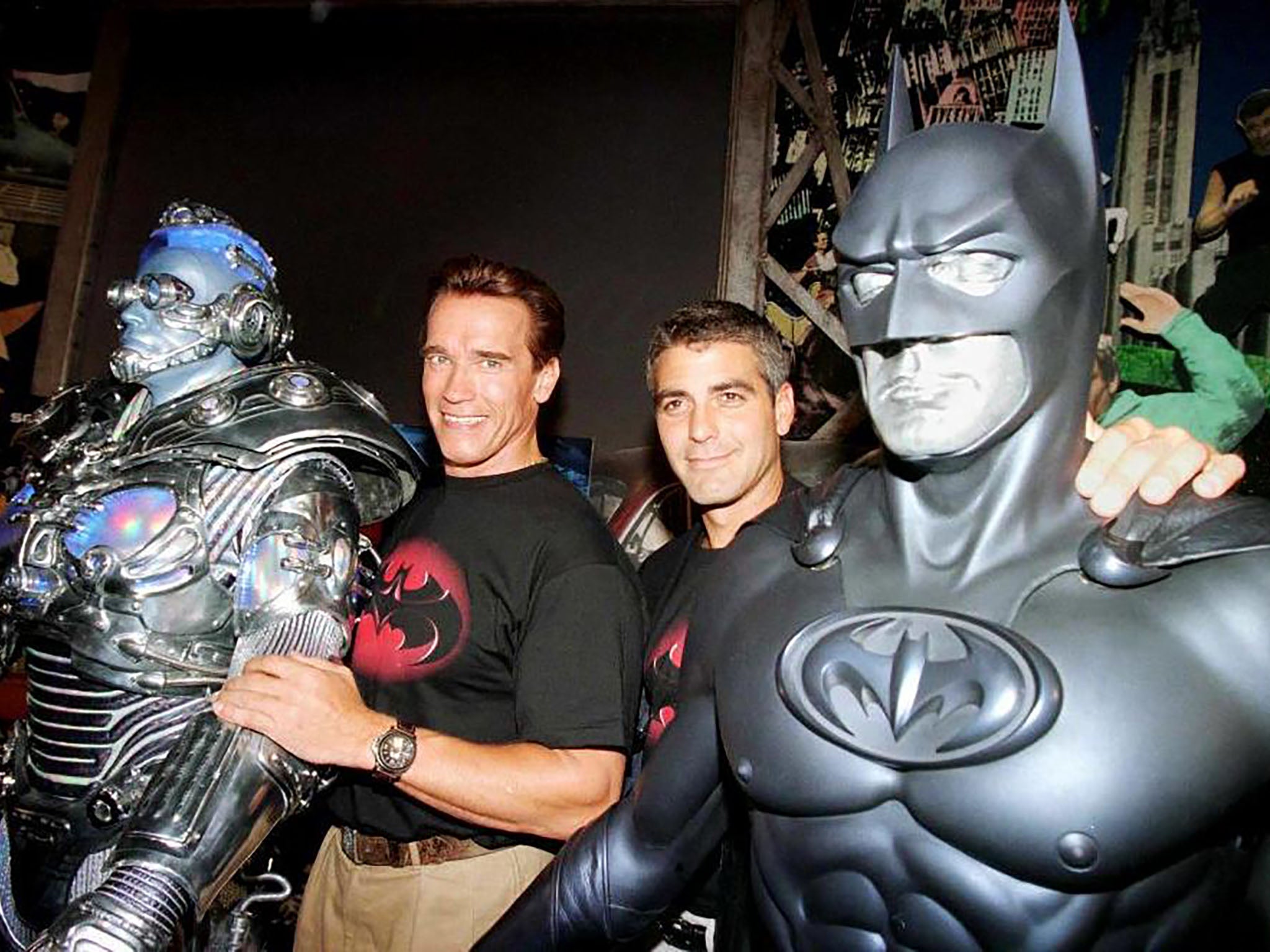

The studio was more interested in bat-dollars. Batman & Robin, released 25 years ago this June, was a merchandising juggernaut – toys, T-shirts, and bat-branded tat. Publicity shots of the dynamic trio – Batman (George Clooney), Robin (Chris O’Donnell), and Batgirl (Alicia Silverstone) – were plastered across every magazine, their hands on hips, bat-nipples out in full force. The film had major Hollywood muscle too: Schwarzenegger as Freeze, and Uma Thurman – just three years from Pulp Fiction – as Poison Ivy. But holy codpiece, Batman! Uslan was right. Decades later, Batman & Robin still hangs from the rafters of superhero hell – a film that seemingly came up with the ice-based puns first (“You’re not sending me to the cooler!”) and worked backwards.

Its reputation is so bad that George Clooney has been apologising ever since. “I actually thought I’d destroyed the franchise,” he later said. Indeed, Batman & Robin came closer to killing the Caped Crusader than any number of Gotham City supervillains.

Along with producing partner Benjamin Melniker, Michael Uslan picked up the Batman film rights in 1979. He wanted to rehab Batman’s mainstream rep – to get away from the “Zap!” “Boff!” and “Kapow!” shtick of the 1960s TV series. Uslan details his producing experience and industry know-how in a new memoir, Batman’s Batman.

Joel Schumacher unfairly gets a lot of heat. He was instructed to make this franchise lighter, brighter, more kiddie friendly – for toys and games and Happy Meals

As a Batman fan from childhood (his first memoir is called The Boy Who Loved Batman), Uslan wanted to put the serious side of Batman on the big screen. The result was Tim Burton’s Batman, starring Michael Keaton as the Dark Knight and Jack Nicholson as the Joker. It swooped into cinemas in the summer of 1989 and made almost half a billion. Batman wasn’t a film, it was a cultural happening. The 1992 sequel, Batman Returns, was like Tim Burton unchained – more gothic, more grotesque.

When Joel Schumacher took over directing duties for 1995’s Batman Forever, Val Kilmer stepped into the suit, becoming the broodiest, plumpest-lipped Batman of them all. The franchise also got a literal glow-up: the ruins of Tim Burton’s bat-vision were illuminated with neon; its villains – Two-Face and the Riddler, played by Tommy Lee Jones and Jim Carrey – were nerve-gratingly loud, in both fashion sense and actual volume.

Batman Forever was the highest grossing film at the US box office in 1995. By that point, the Batman movies were a billion-dollar industry – and the only superhero franchise in town. Schumacher rightly sensed that Warner Bros wanted another Batman and talked ideas with screenwriter Akiva Goldsman. But Schumacher recalled that Goldsman was “leery” about Batman & Robin. “We had a couple of very serious discussions about it, and he was right about it in the long run,” Schumacher told The Hollywood Reporter in 2017. Less leery was Batman Forever production designer Barbara Ling. When Schumacher called her to say they would be making another Batman, she replied: “Joel... we haven’t even scratched the surface!” If Batman Forever was a dayglo alt-reality, Batman & Robin would amp things up even further.

But Batman himself (well, Val Kilmer) didn’t return. The actor claimed that he didn’t get fair notice about production; Schumacher said that Kilmer dropped out at the last minute; and everyone else said they just hadn’t gotten along. Instead, George Clooney – then ER’s resident heart-flutterer – bagged the role. Despite Clooney’s own critique – “I’m terrible in it,” he said in 2020 – he’s a solid Bruce Wayne: all easy charm and big dressings gowns. Clooney’s Bruce/Batman embodied a change: less moping over his dead parents; more worrying about his sickly butler and bickering with Robin (who is annoying). “He was Bruce Wayne as the warm and fuzzy boy next door,” says Uslan. When asked if he had any hand in casting Clooney and Schwarzenegger, or choosing the villains, Uslan’s reply is a resounding negative: “Absolutely not.”

It was Schumacher who wanted Mr Freeze and Poison Ivy. They were perfect for the daft turn the franchise was taking – both at the sillier end of Gotham’s most wanted list. There were rumours that Patrick Stewart would play Mr Freeze, but Schumacher approached Schwarzenegger. “The Terminator meets the refrigerator,” he said (wittier than any number of “ice to see you” puns). Arnie was in transition – from the biggest action star on the planet to self-parodying PG jokester. He felt obliged to play Mr Freeze: Schumacher wouldn’t direct the film unless Schwarzenegger agreed to sign on. “What are you gonna do?” joked Schwarzenegger at the time. “Screw up a whole movie?” Schwarzenegger was promoted as the star attraction and received $25m (£19m) – about $1m for every day he spent on set. Clooney, according to producer Peter MacGregor-Scott, was comparatively “a bargain”.

If the Batman films are defined not by their Batmen but by their villains – and they very much are – one look at Schwarzenegger’s Mr Freeze says it all: a villain who wears polar bear slippers and smokes frozen cigars. Thurman, meanwhile, compared Poison Ivy to an opera role.

Indeed, neither Mr Freeze nor Poison Ivy are subtle. “Those characters would not have been out of place in the 1960s series,” says Andrew Farago, a comic historian and author of Batman: The Definitive History. “It was part of the excitement – Uma Thurman from Pulp Fiction and Terminator 2-era Arnold Schwarzenegger as supervillains. You don’t want them to disappear into the roles. The script and direction encouraged those performances to go over the top.”

It was also Schumacher’s idea to bring in Alicia Silverstone as Barbara Wilson aka Batgirl – a butter-wouldn’t-melt schoolgirl by day and a motorcycle-racing rebel by night – specifically to draw girls and young women to the franchise. Her bat mask is apparently so convincing that even Batman, the world’s greatest detective, doesn’t recognise her when she suits up. “Bruce, it’s me, Barbara,” she says. It’s almost as ridiculous as Mr Freeze’s ice gun.

Batman & Robin, though, knows full well what it is: a deliberate exercise in comic book campery. See the opening action set-piece, set in Gotham’s natural history museum (“What killed the dinosaurs? The ice age!”) with Batman skidding down the neck and tail of a frozen brachiosaurus Fred Flintstone-style. As Schumacher told his cast before takes: “Remember everybody, it’s a cartoon!” But his cartoon-come-to-life became an ad for the tie-ins. “Joel Schumacher grew up on the comics and really wanted to bring a comic book to the screen,” says Farago. “Unfortunately, they were trying to please too many people – toy companies, fast food restaurants, clothing and video game manufacturers. It was not conducive to a great screenplay.”

Uslan agrees. “I think Joel unfairly gets a lot of heat,” he says. “But he was following his orders. He was instructed to make this franchise lighter, brighter, more kiddie friendly – for toys and games and Happy Meals. At that time the movie studios became more like conglomerates. Lots of wheels needed to be greased.”

He adds: “My feeling – which was very strong and very vociferous – was that if you bring in great filmmakers who have a love and vision for the character and they make great movies, you’ll sell toys anyway. But if the toy companies want three villains, three heroes, three costumes, and two vehicles each, then the tail wags the dogs – you’re making something that’s more akin to a two-hour toy infomercial than a film.”

Speaking in a behind-the-scenes documentary, Schumacher – who died in 2020 – explained how designs were being snatched from his hands in pre-production and shipped off to Asian toy manufacturers. “[The response to] everything that we did was ‘Can you make it bigger, can you make it better?’” he recalled. He also admitted: “I’m not criticising anyone. I signed on to do this.”

Batman & Robin was certainly from the “go big or go back to the Batcave” school of Nineties blockbusting, with a budget of $125m (£95m). (“A waste of money,” Clooney said in 2002.) Barbara Ling’s revamped production design is Gotham City with muscles. Quite literally: giant-biceped statues lurch over the streets and towering, chiselled adonises hold monuments in the air. It’s a hyper-real fantasy.

Mr Freeze’s suit was impressive. Designed by armourer Terry English, it cost more than $1m and used 2,400 LED lights. One part – an LED mouthpiece – bled battery acid into Arnie’s mouth. “It tastes like s**t!” Schwarzenegger complained. A body double shouldered the literal weight of the suit for most scenes. As actor Chris O’Donnell said, his Robin does plenty of fighting with Mr Freeze in the film, but O’Donnell himself didn’t work a single day with Arnie.

With a 25-year reputation as a frozen turkey, it’s easy to forget the hoopla around Batman & Robin. Scrutiny from the fans and press was intense. Secrecy was paramount. When a Batman mask went missing from the set, cars were searched for weeks afterwards. Photos of Schwarzenegger in his Freeze gear sold for big money – $10,000 (£7,000), so MacGregor-Scott claimed – and security had to chase photographers away from the set. “I had to walk from my trailer to the stage with people around me holding up cardboard so no one could see or videotape me,” Schwarzenegger told Entertainment Weekly. The biggest headlines pointed towards the rubber nipples on the Batman and Robin suits. “There was more newsprint on the nipples and codpieces than anything I’ve ever seen!” Schumacher told Variety. “What’s wrong with our culture?”

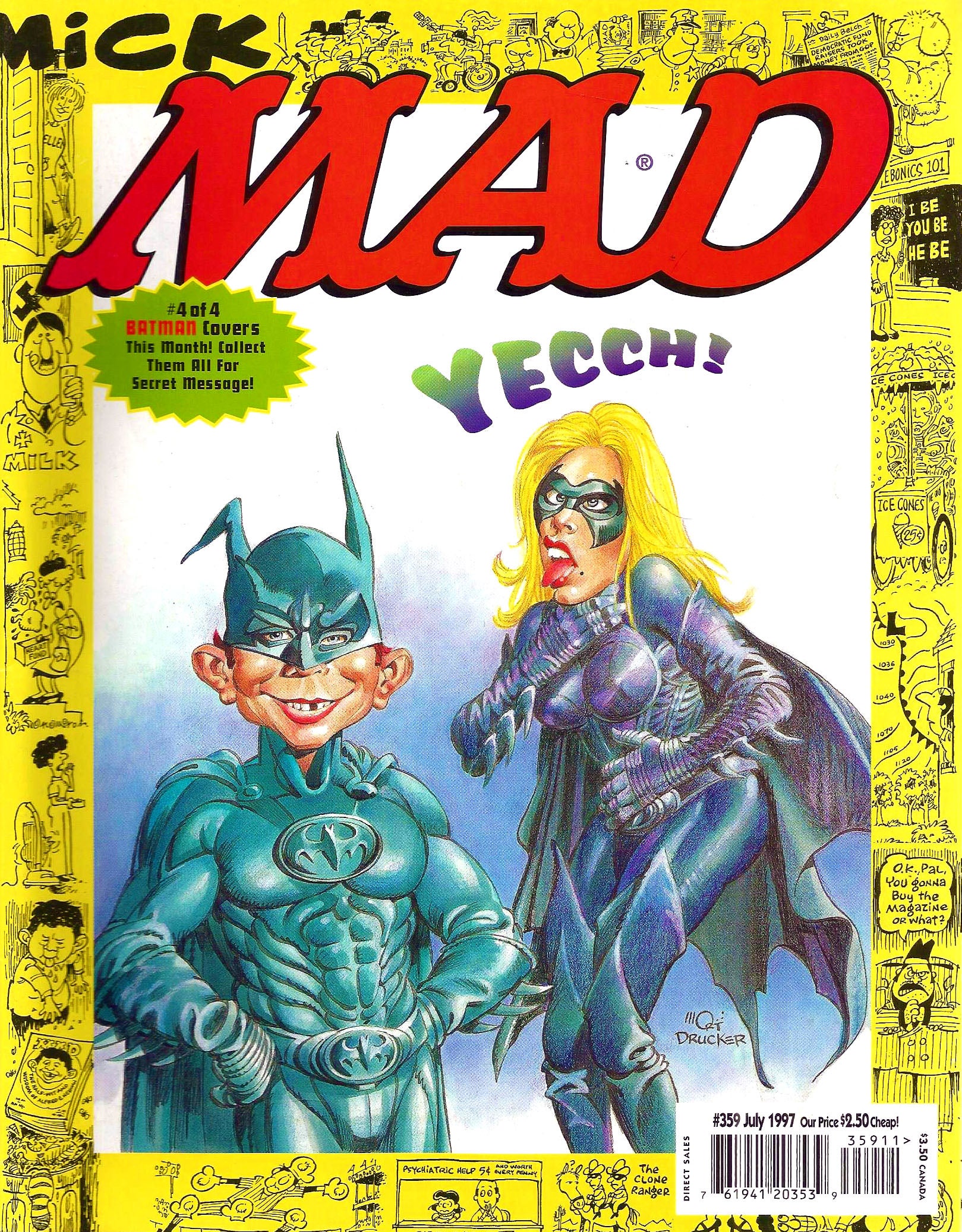

Batman & Robin premiered on 12 June 1997. Reception to the film was, ahem, frosty. “One for the Clooney bin,” said The Observer. Empire slated Schumacher’s overall handling of the Batman franchise: “Let’s hope he doesn’t get his hands on it again.” For comic diehards, Batman & Robin was the ultimate insult. “People looked at the Joel Schumacher movies and thought, ‘This is making fun of us and the characters,’” says Farago.

Schumacher addressed the bat-lash. “It was such a scandal!” he said. “It was like I had murdered babies or something.” Clooney owns it: he keeps a picture of himself as Batman on his office wall – a cautionary reminder – and won’t let his wife, Amal, watch it. “There are certain films I just go, ‘I want my wife to have some respect for me,’” he told Variety last year.

Despite the rep, Batman & Robin wasn’t a total disaster – “It did its job of selling merchandise,” says Farago. “Everyone bought Batman cereal and wore Batman T-shirts that summer!” – but its worldwide take, $238.3m (£182m), was almost $100m below Batman Forever. A third Schumacher film, set to feature the Scarecrow and potentially Madonna as Harley Quinn, was scrapped – sunk by the critical mauling of Batman & Robin. Uslan knew what would happen if Batman & Robin underperformed. “Next time, they’re going to have to give us what we want,” he recalled thinking. “A return to the dark and serious Batman.”

It was a curious time for comic book movies. X-Men and Spider-Man were yet to come out; Tim Burton’s long-in-gestation Superman Lives failed to take flight; Batman, meanwhile, was shelved for eight years. “There was a management change at Warner Bros in those years,” says Uslan. “The first call I got was, ‘Michael, you don’t know me, I’m the new vice-president here, we’re going to reboot the Batman franchise and we’re going to do it dark and serious…’”

Batman & Robin was perhaps a necessary folly – a crucial moment in the evolution of Batman. In 2005, Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins redefined superhero films again – a tradition which has continued with Matt Reeves’s recent The Batman. The comics have followed a similar trend: lacklustre periods followed by gritty reinvention. It’s a testament to the power of the character – that the mythos is bigger than any one interpretation. Even Batman & Robin couldn’t put him out in the cold for good.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks