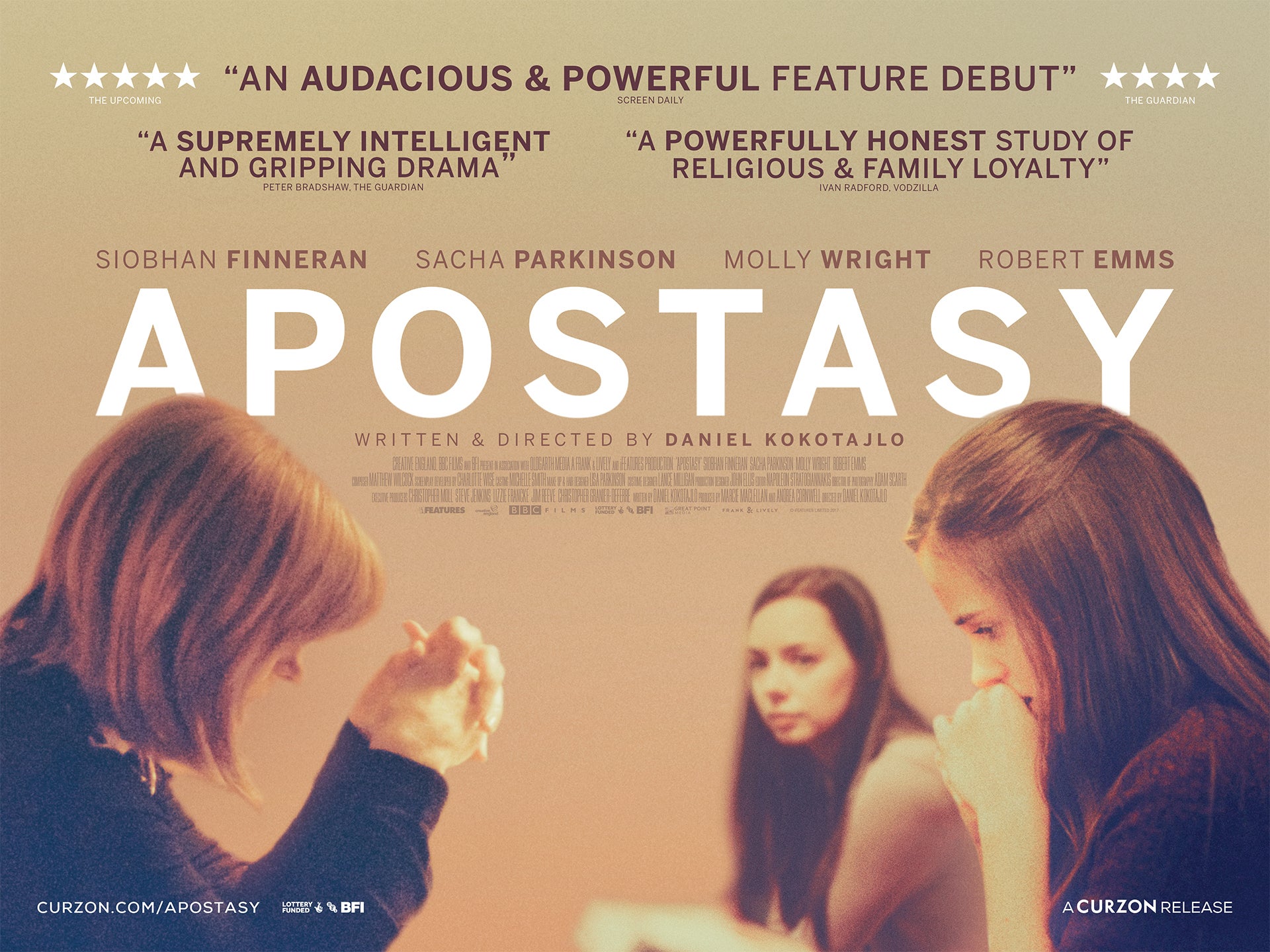

Daniel Kokotajlo on how his upbringing as a Jehovah’s Witness informed new film Apostasy

The British director’s debut film pulls back the curtain on the religious organisation, with a fictional tale of a family torn apart

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“It’s a world that people don’t really know much about,” says British filmmaker Daniel Kokotajlo.

He’s telling me about his debut feature, Apostasy, which pulls back the curtain on the lives of Jehovah’s Witnesses. The director knows this world better than most.

He was a Witness himself for 10 years, dutifully handing out copies of The Watchtower (their monthly magazine) in the street, attending meetings at the Kingdom Hall, and knocking on strangers’ doors in an attempt to help them gain everlasting life.

Most people, Kokotajlo says, only see Witnesses when they’re out and about – by the Tube station, at the bus stop, knocking on your door. “But you don’t really know what some of them have to deal with on a day-to-day basis. They’re very disconnected from the world around them.”

Set in Oldham, Manchester – just down the road from where Kokotajlo grew up – Apostasy zooms in on the turbulent life of one such disconnected family. The fictional story – rooted in real-life experiences of ex-Witnesses that Kokotajlo spoke to, and the director’s own memory of what it was like to be a Witness – follows a mother and her two daughters, Alex and Luisa.

Their lives as devout Witnesses are upended the moment Luisa, the eldest daughter, becomes pregnant.

She’s swiftly “disfellowshiped” – booted out, named and shamed during a meeting at the Kingdom Hall. Luisa’s mum is heartbroken and humiliated. She heeds the words of the elders to “keep any necessary contact to a bare minimum”.

Witnesses must put Jehovah first, they say, “even before our family”. In other words, this mother is forbidden from seeing her own daughter.

These teachings of the religion are placed under the microscope in Kokotajlo’s eye-opening drama. What if you grow up following this religion and then start to disagree with its teachings? How do they – the elders – deal with an impulsive freethinker like Luisa? Apostasy is ultimately a devastating look at how one family’s life is torn apart navigating these issues.

If the premise sounds far-fetched, it’s not. There are articles on The Watchtower’s website that outline “How to Treat a Disfellowshipped Person”. They say the Bible asks us to “Stop keeping company with anyone who is sexually immoral”, and that “strict avoidance” is absolutely necessary; you should “not even eat with such a man”.

Why? Because “the one who says a greeting to him is a sharer in his wicked works”.

Kokotajlo’s own story of how he left the faith isn’t as dramatic as Luisa’s. “It was a slow, gradual fading away from the religion,” he explains. “Growing up as a teenager and eventually going to art college – that was when I started to really think differently about things.”

There, his tutor would ask him what his opinion was on various conceptual artworks. He realised there was no clear answer. “That was the thing about going to the Kingdom Hall, everything is very black and white: there’s always an answer.”

When he was a young Witness, Kokotajlo found the religion’s doomsday narrative seductive. “They would say to us, ‘Don’t worry, you’re not even going to grow old, you don’t need to worry about things, you don’t need to plan, because the end of the world is coming shortly.’ As I got older, that became more and more unrealistic,” he says, referring to the failed prophecies of Armageddon, of which there were five in the 20th century, the last of which was prophesied for the turn of this century.

Though Kokotajlo didn’t have direct experience of disfellowshipping and the way that families are forced to shun their own flesh and blood, it had happened to people that he knows. “I’m a member of a lot of ex-Witness support groups out there and there are millions of people who’ve gone through this experience.”

Luisa’s heartbreaking story really had happened to another Witness. The film was inspired by a secret audio recording of a reinstatement meeting that Kokotajlo discovered when he started working on the script.

“It was a young woman and she’d had a baby and she’d not spoken to her mum for over eight months,” he says. “She had to move out, and her mum came round one day to clean her fridge out and these guys [the elders] were not having it. They were just trying to come up with any reason not to reinstate [the daughter]. She was doing her best to get reinstated, and she just has a breakdown.”

When I dig a little deeper into Jehovah’s Witnesses online, I discover a slew of YouTube videos made by former Witnesses. The titles range from “Secrets from the Cult – An Ex-Jehovah’s Witness Speaks Out” to “How I Got Disfellowshipped From Jehovah’s Witnesses/Escaping the Cult”. Many feature the words “cult”, “brain conditioning” or “brainwashing”.

What does Kokotajlo think of such labels? “I can understand it,” he says. “I’m in a tricky position because I understand how they feel, but at the same time I can appreciate how it helps a lot of people and why people have faith today. And I can see what good it does for my own family.”

He’s said previously that he’s not sure how his own mother feels about the fact that he’s drifted from the religion. Yet he still has a good relationship with her, one that wasn’t strictly discouraged by the elders, given that he wasn’t disfellowshipped like Luisa.

But he tells me his family probably won’t see the film. “It’s too close to the bone,” he says. “They’re not gonna feel comfortable watching it.”

More importantly, will it cause any problems for them upon its release? “I’m not sure,” he says. “I think it depends on The Watchtower’s stance on the film. If they tell people not to watch it, then that might become an issue.”

He does agree that there’s a certain kind of conditioning that goes on at the Kingdom Hall. “It is group thinking, it is a system that’s designed to make everyone think the same way and say the same things – so it’s up to you whether you consider that brainwashing.”

Make no mistake: Apostasy is critical, just not in a preachy, ram-it-down-your-throat way. Kokotajlo calls it “provocative”, in the sense that he’s dealing with issues within the religion that he doesn’t agree with – “the excommunication, the way that they punish people, the blood issue” (Witnesses believe that Christians should not accept blood transfusions, or donate or store their own blood for transfusion).

Yet he does have compassion, he says. “I do care about the Witnesses and the people in the religion. And part of me was hoping that if they did see it – if it was articulated in a certain way – they could maybe see their own lives on screen and they would start to question it, because they have some sort of objectivity seeing it like that.”

But Kokotajlo thinks some Witnesses will steer well clear when they spot the title. “‘Apostasy’ is a strong, provocative word within the religion, so I suspect staunch members would run a mile.”

He adds that, when The Independent ran an exclusive trailer under the headline “Jehovah’s Witness drama being hailed as best British film in years”, Witnesses shared the link without fully realising what it was.

“They thought it was a film made by The Watchtower. When they did realise, a lot of them were saying, ‘Look how Satan has tricked us; God will rectify it’.”

Some ex-Witnesses were among the audience at the film’s world premiere in Toronto last year. The response was mixed.

For some, Kokotajlo says it was a cathartic experience, while others were still too emotionally invested in it. “They’ve recently gone through the experience and they’re quite triggered by the film and struggle with it,” he explains.

Then there were some who were still extremely angry with the religion and what it’s done to them. “Maybe they were hoping it would be a much more critical or damning piece about the Witnesses.”

And for Kokotajlo, a former Witness coming to terms with his own past and mining his memories for his movie, was the experience cathartic?

“Not yet, no,” he laughs. “Because I had to open up that can of worms again. I felt like I had dealt with it and moved on in life, and then years later I’ve had to go back to it all.”

But in the end, he says he’s grateful for the experience. “I’ve been able to look at issues that I’d maybe ignored earlier in life. Maybe once the film is out – maybe when I move on to the next project – it might start to feel different.”

‘Apostasy’ is released 27 July

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments