Antonio Banderas on playing Picasso: 'The ghost just gets in your body'

The actor grew up in the same Spanish town as Pablo Picasso. Now, Banderas finally gets to play his childhood hero – and defends the painter against accusations of misogyny

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

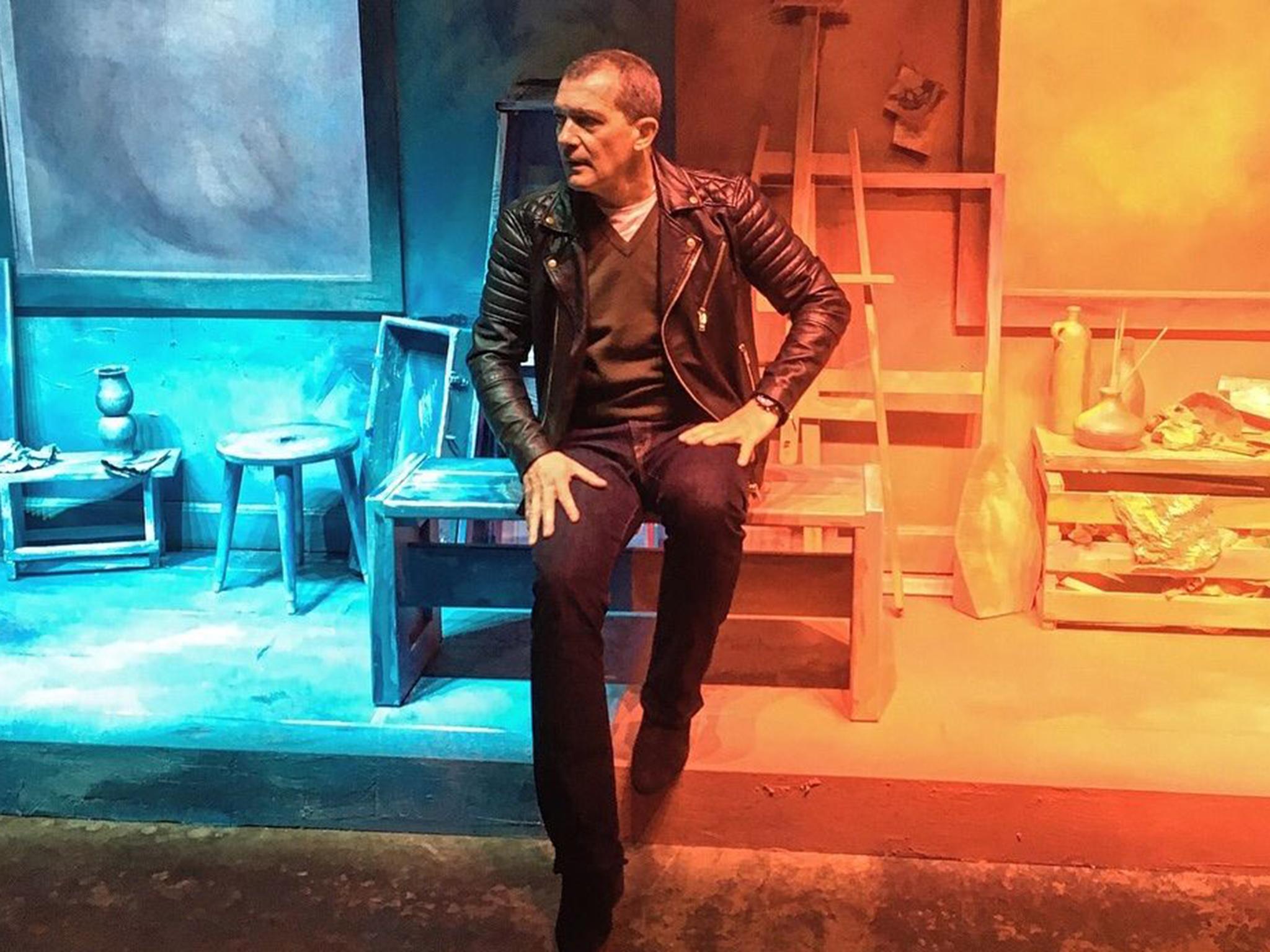

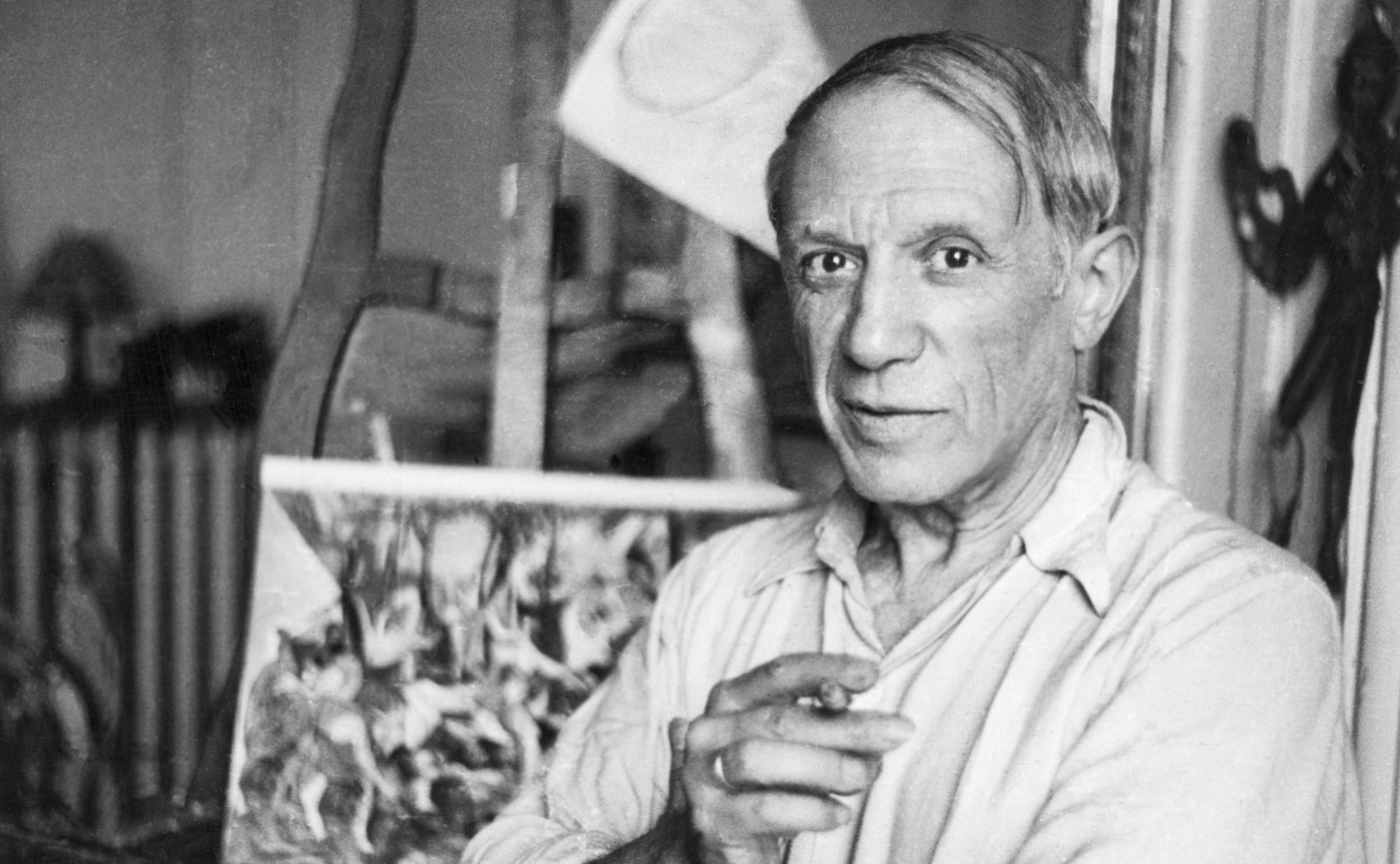

Your support makes all the difference.By the time Antonio Banderas shaved off his eyebrows and hair to play Pablo Picasso – his lifelong hero, his towering standard of greatness – he had already been asked to portray Picasso twice. “Oh, yes,” he said. “Twice before.”

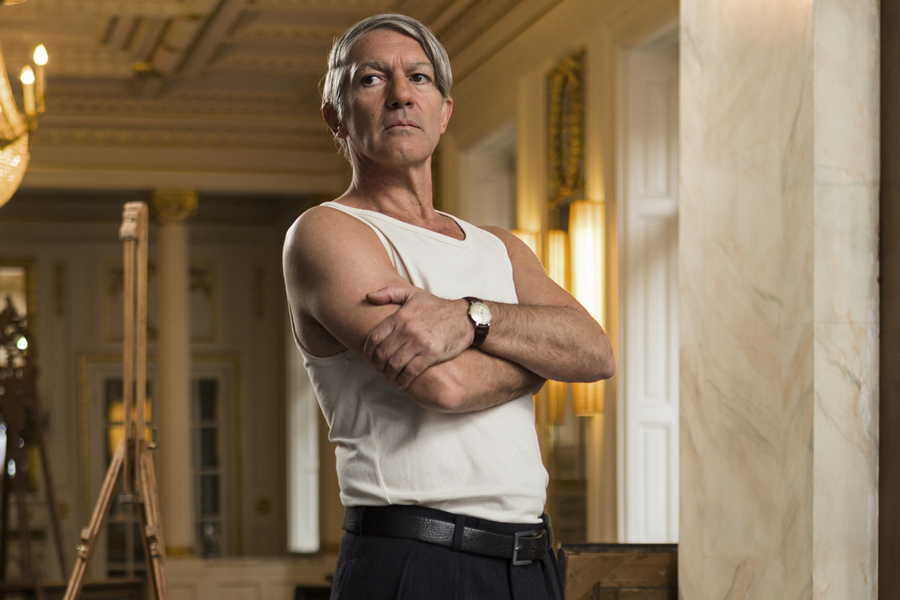

He sits in a director’s chair, his face contorted into a thoughtful expression, complete with chin strokes. On his nose, cheeks and chin, he wears silicone prosthetics for the features he does not share with Picasso: to thin out his featherbed lips, to make his nose fleshier and his jowls jowlier, to mask his beautiful face. It doesn’t work. The minute you look at him, his chocolate pudding swimming pool eyeballs give him away.

It is his last day here before heading to Malta for the final leg of shooting for NatGeo’s Genius, an anthology series that focuses on Picasso in its second season and will have its premiere Tuesday. The Picasso he is playing today is 67. When he is shooting, he assumes the posture of a 67-year-old, but when he isn’t, he is Antonio Banderas, a human exclamation point, his face an orchestra of intense expressions. (A better way to put it: his friend Salma Hayek told me that out of all the characters he’s ever played, he most resembles Puss in Boots in real life.)

Oh yes, by the time he shaved off all vestiges of hair above his neck, he already had a long, full career. He was already a star of great renown in Spain, where he had served as a muse to Pedro Almodovar for seven movies. He had already received accolades for his performance in 1992’s The Mambo Kings, a performance so openhearted and passionate that few noticed that his only English at the time was in the form of phonetic imitation. He had already wooed US audiences with his intimate portrayal of Tom Hanks’ lover in Philadelphia.

He had helped Robert Rodriguez, another director who loved him, achieve US acclaim via Desperado and the Spy Kids movies. He had swashbuckled his way into children’s hearts as a sultry, shod cat in the Shrek spinoff, Puss in Boots. He had directed two movies. He had serenaded in Evita and simulated French-kissing with Catherine Zeta-Jones through two of the most alive iterations of Zorro we’d ever seen. He had seduced his way to a Tony nomination for an energetic Nine. He had Angelina Jolie’ed with Angelina Jolie in Original Sin.

He was a beloved fixture in US cinema – a masked avenger, a Latin lover, a mariachi, a matador, an assassin posing as, oh yes, a mariachi. He bided his time in masks, with guns, with swords; as he grew older, he was rewarded with the chance to play (or almost play, in projects that got killed) historical figures: Dali, Mussolini, Pancho Villa, and Picasso – and Picasso.

And now it is finally happening. He is going to play his boyhood hero and bring pride to Málaga, Spain – both his and Picasso’s hometown. When Banderas was growing up, his mother would stop in front of the house the artist was born in every time they passed it and say, “Look, Antonio”. Now, in the home he owns in Málaga, he can see that house from his terrace.

All this, and still, when Banderas sits down in a director’s chair next to me, after I congratulate him on what must be a significant lifetime achievement, he shakes his head and says I have it wrong. Sure, it’s great, this work is great. But it’s not the ultimate. Not yet. “Oh, no,” he says, leaning in close. “I still don’t think I have done the thing I will be remembered for.”

In between dropping existential depth bombs, Banderas tells stories. He stands with his legs spread apart, his head thrown back and his arms raised to the side and says that Salvador Dali liked to put honey on his lips after a meal so that flies would gather and crawl all over his face. “He found it to be an erotic experience,” Banderas syas, as he closes his eyes and plays piano fingers over his lips to imitate the flies. Did you know that Dali (allegedly) hated blind people? He thought they were faking. “He would cross the street to yell at a man walking around like...” He feels around with an imaginary cane and laughs. “Ay, was he crazy.”

He is dressed for the day’s scenes in a tank top under a silk button-down shirt and trousers hiked up to around his fourth rib, a particular kind of European old-man fashion. He wears over his bald head a sparse netted gray wig, since Picasso had Dr Phil pattern baldness and Banderas still has a full head of hair. He could have worn one of those rubber caps, but if you think he would, you don’t know Banderas. He would never do that. He would never not take the opportunity to come even closer to the character.

He considered Picasso, really considered him. They started out so similar, but it’s easy to confuse details of birth with the way a man turns out. Take their treatment of women, for example. Hayek says that Banderas is such a good friend that when he read her essay in The New York Times about being harassed by Harvey Weinstein, he was among the first to call her. He wanted to know why she didn’t tell him what Weinstein was doing back when Banderas was making a cameo in her movie Frida. He was the first person to call the minute she was nominated for an Oscar for the role.

Picasso, on the other hand, said that “women are machines for suffering” and that, to him, they were either “goddesses or doormats”. Genius: Picasso addresses the artist’s misogyny as much as his art. In the first episode a woman is home with his offspring while he makes out with another lover on the beach, and both women get in a fistfight in front of him while he is painting Guernica.

Honestly, I tell him, the lionisation of a man who treats women this way is gross to me.

Banderas beseeches me to be more generous. “The problem with Picasso from my point of view, I don’t think he abused women, as we understand that now,” he says. “The problem is that he wanted everything, everything, all the time.”

He enters a project with maximum dedication, maximum research. The more you know about a character, the more you can fill the white spaces with something rich. He asks: do you know that Picasso’s grandson Pablito apparently stood on a street near his home in France with a sandwich board when his grandfather wouldn’t allow him to visit him in the final days? Go ahead, ask him anything.

If you know your subject down to his soul, then the subject is there when you need him. “I’ve been with him now for months every day, and I can just actually say, ‘OK, come over here’. The ghost comes and just gets in your body and you’re... ‘boom’.”

On the days it doesn’t come so easily, you can fill the white space with you. Who is to say where Picasso ends and Banderas begins? Who can give that information now that he’s prepared for this role three separate times?

Kenneth Biller, a creator of the show, and Ron Howard, an executive producer, immediately thought of Banderas for the role. They worried that they’d have to persuade him to play the part, but he jumped up (pop!) and agreed to do it. He had recently happened upon the first season of Genius, with Geoffrey Rush as Albert Einstein, while cruising on his Apple TV. He watched the whole thing in two days.

Genius: Picasso, which takes place over 10 episodes, is shot during two eras: Picasso’s youth, and his old age. In his younger days, he is played by Alex Rich, who does a Picasso impression that is actually an Antonio Banderas impression. The camera follows Rich to show the freneticism of youth. But during the old age scenes, the camera stays still, like a portrait with Banderas entering and leaving it. In those scenes, it’s Banderas who supplies the energy.

How wonderful. How wonderful to find in your late fifties a character that’s been so meaningful. You can maybe understand that after all the years of masks and tangos and needing to drip with Andalusian lust, it’s nice to play someone who is considered a genius. Oh yes, it is nice to finally play someone who has touched greatness.

Had Banderas stayed in Spain, this would have been an entirely different story. He would have continued on the path Almodovar had set for him, playing men with depth and inner lives. But he didn’t – he couldn’t.

In 1981, while sitting at Café Gijón in Madrid, a man with a red briefcase held court telling funny stories. Banderas had long hair and a moustache for a role in a play. The man looked at him and said: “You should do film cinema. You are very romantic and you have a romantic face.” Banderas said: “OK. Cool.” Afterwards, he asked other patrons if anyone knew who the man was. “They said to me: ‘He’s called Pedro Almodovar. He made one movie’” – he had, in fact, already made two feature films and several shorts – “’but he’s not going to make any more.’”

Two days later, Almodovar came to see Banderas in the play. In the dressing room afterwards, he asked Banderas if he wanted to do a movie with him. “Sure,” Banderas said. Their first movie was the 1982 comedy Labyrinth of Passion, in which he plays a terrorist.

They made six more movies together. He played complex, brooding men – people with souls. In Spain, for Almodovar, the soul was inherent in the character. Later, in the United States, working for US directors, Banderas had to create his characters’ souls.

He had a choice. He could go back to Spain and work with great directors – the star system there revolves around auteurs, not actors – and there was no shortage of deep, complex roles for him.

His fellow Hispanic actors asked him: “So, are you going to stay in America?” He told them: “Well, I don’t know. Maybe. Yeah.” They told him: “Well, if you stay here you’re going to be the bad guy, number one.” They told him he would only ever get cast as a member of a cartel or a gang.

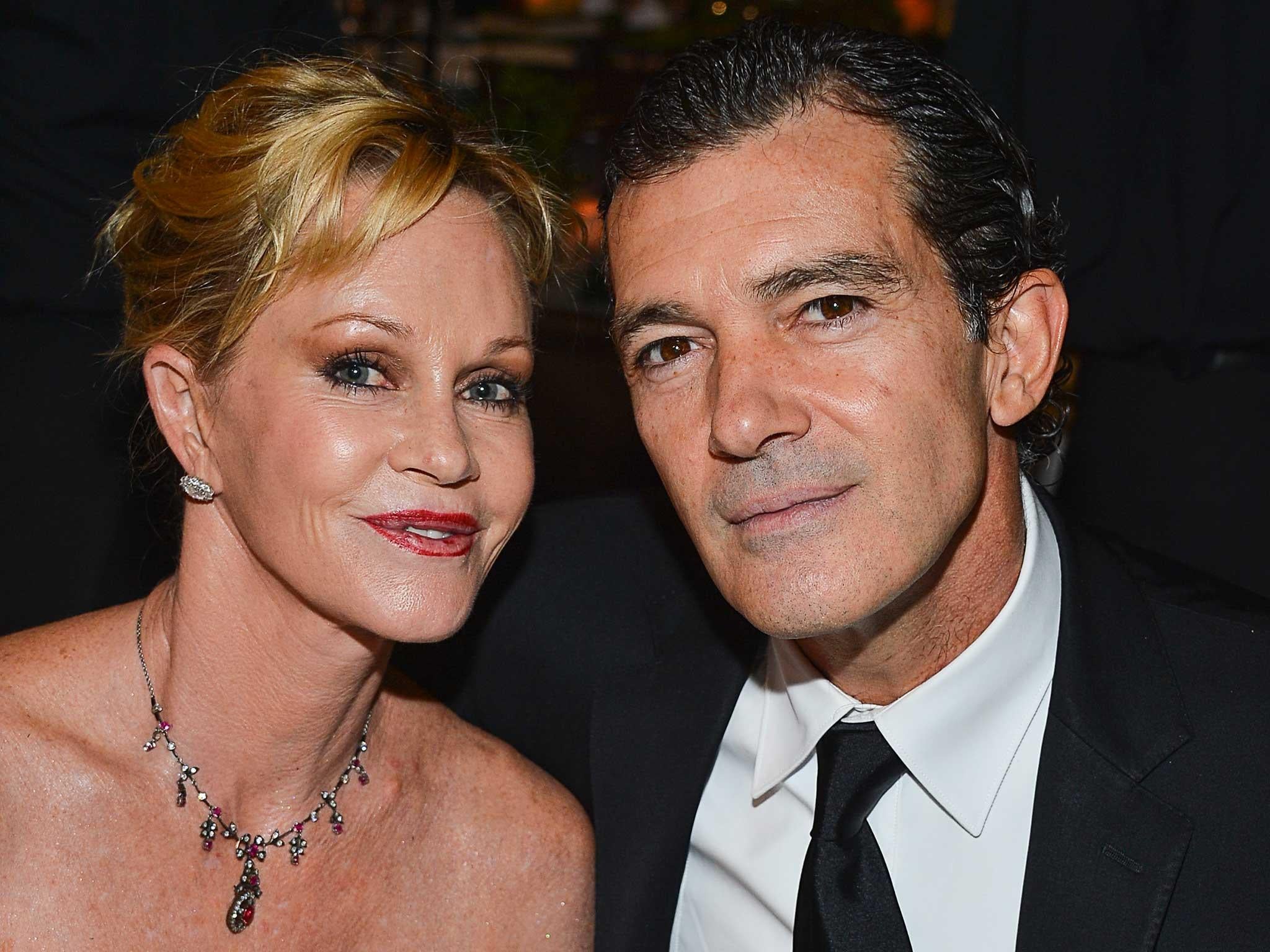

But it was too late. By 1996, he was married to Melanie Griffith. They had a daughter, Stella. He had grown attached to his stepchildren. The question became one not of artistic fulfilment but of practicality. “How can I keep my career here? I’m married here. I live here. I have to play here.”

And he loves America. “The culture here...” He shimmers with delight. “There is something very beautiful about America, very innocent. Oh, yes. It’s still new. It’s innocent.”

I express some surprise. Over the course of my time in Hungary with him, we’ve had the mass school shooting in Parkland, Florida. America has become horrifying to me. “Yes,” he says. “But you guys believe. You believe everything – even in this moment, you believe.” In Europe, he says, people are sceptical. There’s the weight of history. But America, man. “I love Nasa. I love those institutions. And I remember visiting Houston and going there and me doing my eyes like this.” He makes his eyes big and full of disbelief.

And the innovation! “These people that invent Googles and Apples and all these companies, they put heart in the skies. Elon Musk doing this thing is unbelievable to me.” So he plays what he called the “exotic guy”. His agent tells him he becomes more powerful the more he says no. “But,” he says, “I have a problem here, because I have to build a career almost handicapped.” He knows he was offered jobs that weren’t quite the best, jobs that had been offered to five or 10 actors before him.

“I cannot play in the same league as certain American actors, because my accent didn’t allow me just to play a banker from New York or an astronaut,” he says. “So I have to be balancing. And it’s almost like the guy in the circus that tried to keep all the plates going. And if he stops, they fall. And so I did have to do in my career things that I wouldn’t have done, yes.” What can he do? “It was a desert for Spanish actors.”

But lately, a strange thing has started happening. He’s not being asked to wear matador outfits anymore. At the ripe (but still extremely handsome) age of 57, the roles got better. “They have more weight, they are more complex, they are more profound, and I enjoy more to play them, because you can just actually find many different ways to play,” he says. “It’s almost like a pot and you can’t stop putting things in. Before, it was a uniform almost. They wanted the heroic, the epic, the guy.”

Banderas lives in England now, in Surrey, about an hour south-west of London. He lives there with his girlfriend, Nicole Kimpel, an investment adviser he met at Cannes a few years ago.

The truth is, he doesn’t need to be in America anymore. So many movie shoots are done in Europe now for tax reasons. And Kimpel has an identical twin sister who lives in Switzerland and whom she can’t bear to be too far away from.

What did he need to stay in the United States for anyway? His days of co-parenting are over. Stella is off at the University of Southern California, studying cinema. Of his divorce from Griffith in 2015 he says: “Melanie is a very generous woman and an excellent mother and a great lover for many years. But there is a moment that things were not working, and before we started damaging each other we just decided to take that option.”

Here’s the truth about why Antonio Banderas stayed in the States for so long. Yes, he got married. Yes, he loved Nasa and the Googles. Yes, he loved our innocence. But you know what else? He won’t say it, almost out of fealty to the country he was born in, but Hayek and Rodriguez will. In Spain, Hayek says, “he could not do some of the action movies. He’d never been on Broadway.”

In Spain he could do a lot of interesting work. But in the States, he can be an action star, a comedy hero, a Nasonex bee, a spy dad. In Spain he could be in the theatre, yes, but in America, he can be on Broadway. Banderas says the year he was in Nine? was his happiest time in America.

That’s who Antonio Banderas is. “He’s someone who wants to eat the world,” Rodriguez tells me.

‘Genius: Picasso’ is on National Geographic from 24 April

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments