Stronger than Fiction: Jeffrey Wright’s Oscar favourite has more to say than your average author film

The satirical comedy is hotly tipped for an Oscar next year, securing its place in a long lineage of brilliant films about neurotic writers, from Barton Fink to The Shining. But, as Geoffrey Macnab argues, ‘American Fiction’ has a humour and pathos that transcends the genre

Political correctness doesn’t come easy to Thelonius “Monk” Ellison, the anti-hero played by Jeffrey Wright in American Fiction, Cord Jefferson’s coruscating new satirical comedy adapted from the 2001 novel Erasure by Percival Everett. Monk is a talented author who hasn’t completed a new book in years. For that reason, he is also a professor – one with a knack for offending his students. He’ll ask the German ones if they’re descended from Nazis and he horrifies the snowflakes by writing the N-word in big letters on the blackboard during discussions of Southern Gothic writer, Flannery O’Connor.

More than anything, Monk is infuriated by the condescension shown toward Black authors by the white cultural establishment. All publishers want from him are stories about gangs, poverty, pimps, single mums, drug addiction, and Black oppression.

“They want a Black book,” his agent offers by way of explanation as to why editors have once again turned down his latest work; it doesn’t reflect the authentic “African American experience”. Monk growls back, “They have a Black book. I’m Black and it’s my book.”

The versatile Wright, who played 007’s best friend in the Daniel Craig Bond films and has been seen in everything from The Hunger Games and The Batman to Wes Anderson and Julian Schnabel movies, is being tipped for an Oscar nomination for his wonderfully sly and affecting performance as Monk: a thoughtful, middle-class man simmering with explosive resentment. On his professor’s salary, he can barely afford to pay for his elderly mother’s medical care. The inanity and hypocrisy of white mainstream American literary culture infuriate him.

Eventually, Monk gives the people what they want. He pretends to be an ex-con and pens a spoof ghetto novel. “It’s got deadbeat dads, rappers, crack – and [the hero] gets killed by a cop at the end,” he says, listing off its magic ingredients. He first calls the book My Pafology before later changing the title to the more direct F***.

Inevitably, the novel, which he publishes under the pseudonym Stagg R Leigh, becomes a huge bestseller and it’s soon optioned by movie studios. The media fawn over this hot new literary sensation from the wrong side of the tracks. In interviews, Monk feigns toughness and mugs mean, fooling everyone into believing that he’s a street thug who somehow fell into writing between drug deals and gun battles. To Monk’s dismay, everyone falls for his act. “The dumber I behave, the richer I get,” he observes.

Wright’s character is the latest in a long line of writers in movies who are troubled, irascible, deceitful, and neurotic. When authors are portrayed on screen, there is almost always something gnawing away at them. They’re alcoholics (Ray Milland in Billy Wilder’s 1945 drama The Lost Weekend) or losing their sanity (John Turturro in the Coen brothers’ dark 1991 comedy Barton Fink). They might have Kathy Bates lurking over them, ready to break their ankles with a sledgehammer if they don’t behave (James Caan in Rob Reiner’s 1990 Stephen King adaptation Misery) or they may succumb to terminal illness (Ben Whishaw as the doomed romantic poet John Keats in Jane Campion’s 2009 biopic Bright Star). Several are wantonly self-destructive (Leonardo DiCaprio’s Arthur Rimbaud drowning in absinthe in 1995’s Total Eclipse).

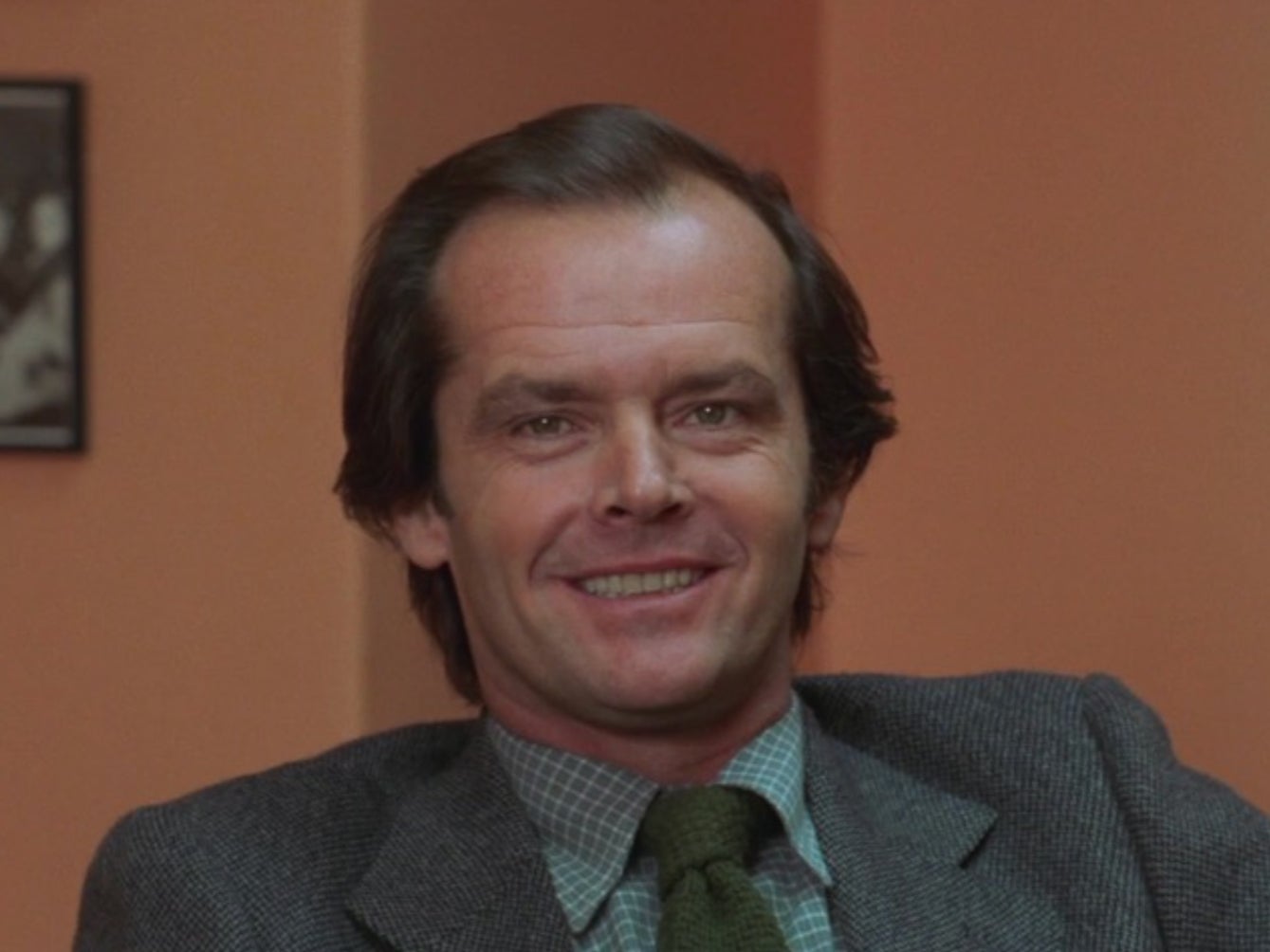

Most writers on screen tend to have a mean streak, too. The combustible scriptwriter Dix Steele (Humphrey Bogart) in Nicholas Ray’s brooding film noir In a Lonely Place (1950) picks a fight at the traffic lights in the very first minute of the movie, gets into a barroom brawl moments later, and soon after becomes a suspect in a murder case. Bogart may have been hardboiled as a private eye but he’s yet more intimidating sitting behind a typewriter. Contemplating this gallery of oddballs, you begin to think that maybe Jack Torrance, the deranged, axe-wielding writer played by Jack Nicholson in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), who once seemed an outlier, isn’t such an extreme case after all. Monk shares several of Jack and Dix’s obsessive traits. He’s an angry, alienated figure, ready to snap at those closest to him.

You have to look very hard to find any films at all about happy writers (although Gary Oldman’s Herman J Mankiewicz in Mank at least knows how to enjoy himself). Their gripes are endless. They’re not paid enough. Their inspiration has dried up. They’re blocked. They suffer from status anxiety. Their erratic behaviour sabotages their relationships. They’re loners. They’re plagiarists – or they have been plagiarised.

Even movies about successful novelists tend to be on the bleak side. Take the 2013 Charles Dickens biopic, The Invisible Woman. The much-loved Dickens, one of Britain’s most celebrated writers, is played by Ralph Fiennes as a moody and mercurial figure with a messy private life. Disgusted sexually by his wife, he embarks on a secret affair with young actor Nelly Ternan (Felicity Jones) but refuses to acknowledge her publicly.

Recent features like Goodbye Christopher Robin (2017) and Tolkien (2019) suggest that similarly revered British authors like AA Milne and JRR Tolkien were deeply scarred by their experiences during the First World War. If it hadn’t been for the horror of the Somme, it’s implied, we might never have got Winnie the Pooh or The Hobbit. Period British biopics about Dickens, Milne and Tolkien are a long way away from the race politics of the contemporary US book world satirised with such relish in American Fiction. Nonetheless, Monk has plenty in common with his predecessors.

Alongside the barbs it aims at the publishing industry, American Fiction includes several enjoyable sideswipes at Hollywood. One of the more ridiculous characters spotted in the latter part of the film is a supremely narcissistic film director (Adam Brody) who is always pressing Monk to come up with a better ending for the big screen adaptation. The director doesn’t want schmaltz or reconciliation. Violence and despair will do just fine. After all, this is an “African American” story. “Nuance doesn’t put asses in movie seats,” he warns Monk.

As we all know, writers have always been treated abysmally in Hollywood. They are hacks for hire, individuals working in a collaborative medium – a fact bitterly resented by many. There is a famous, oft-repeated story about director John Ford that sums up perfectly where writers stood during the classical studio era – and not much has changed since then: a bean-counting exec came onto one of Ford’s sets and told him he was many days behind schedule. Ford responded by picking up the screenplay, ripping it in two, throwing half the pages away and telling the executive, “Now I am back on schedule.”

“If you had creative feelings like we all did, you could get your heart broken,” Donald Ogden Stewart is quoted as saying in last year’s epic tome Hollywood: The Oral History. “Writers are vastly underrated and underpaid,” agreed Billy Wilder in the same book. Contemporary screenwriters still feel scorned and under threat. The recent Writers Guild of America strike, which lasted 148 days, revealed how worried they remain about everything from AI usurping their jobs to streamers eroding their incomes. Monk, though, doesn’t seem to mind the studios’ scornful attitude toward him. At least it has nothing to do with race – just money.

There are obvious reasons why films about writers so often deal with misfortune and madness. For one thing, there wouldn’t be any drama otherwise. Imagine The Shining if Jack checked into the Overlook Hotel, spent an industrious winter there and successfully completed his play – or if John Turturro’s playwright Barton Fink turned up in Los Angeles and set to work immediately on the script for his Wallace Beery wrestling movie. Writers, though, make especially entertaining protagonists. They cannibalise their lives when they have nothing else to draw on; they exaggerate wilfully and look for angles through which they can exploit their misery. As an occupation, it often attracts big egos and conflicting personalities; the act of writing brings up knotty questions of authenticity and profitability. In American Fiction, Monk hits pay dirt by becoming the sort of novelist he despises: one who monetises his “Blackness” for white consumption.

As in so many movies about writers, the neurosis and resentment fuel the comedy. Monk is unhappy as an unsuccessful author but unhappier as a successful one; the more miserable he gets, the funnier he becomes. It’s certainly part of the reason why critics and audiences have been falling in love with what must have seemed on the page like yet another downbeat story about a disgruntled author. There is humour and pathos in Monk’s predicament. Here’s a witty guy who doesn’t mind being the butt of the joke – and that’s why we root for him even when he’s at his grumpiest.

‘American Fiction’ is released in cinemas on 2 February 2024

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks