Alien: How Ridley Scott’s masterpiece has stayed relevant for 40 years

The intergalactic horror film remains one of the most influential films in recent history. Ed Cumming looks back at the blockbuster that introduced the world to Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley

Speaking about his most enduring masterpiece, the director Ridley Scott said he wanted Alien to be an “unpretentious, riveting thriller, like Psycho or Rosemary’s Baby”. It is ironic that perhaps no other film has inspired as much pretentious commentary. Its 40th anniversary today provides a good opportunity to add to the pile. Alien has proved an ideal text for academics, a deep well – or perhaps a totem pole – of Freudian allusion from which critics and theorists have drawn whatever they fancied.

Since it was first released, every frame of the film has been pored over for meaning. James Cameron’s excellent sequel, Aliens, has been studied too. (The other films in the series, not so much.) Most of this attention has been occupied by the character of Sigourney Weaver’s Ellen Ripley and the Swiss artist HR Giger’s terrifying design for the alien, or “xenomorph”. But the androids, the spaceship, the uniforms and even the ship’s cat have come in for analysis. In 2019, the rise of the Alien-academic complex shows few signs of slowing down.

Partly this is due to the quality of the film. Despite many imitators, the original is still the most gripping sci-fi horror ever made. Its pacing, with a slow start building to a frenetic climax, is masterful. Its design has held up where more recent films look dated. For sci-fi, it depends remarkably little on technology. There are spaceships and weapons and androids, but they are not the main focus. The further we get from the time the film was made, the easier it is to see Alien as an artefact separate from its contemporary technology and the less egregious its clunky computer screens, for example, seem.

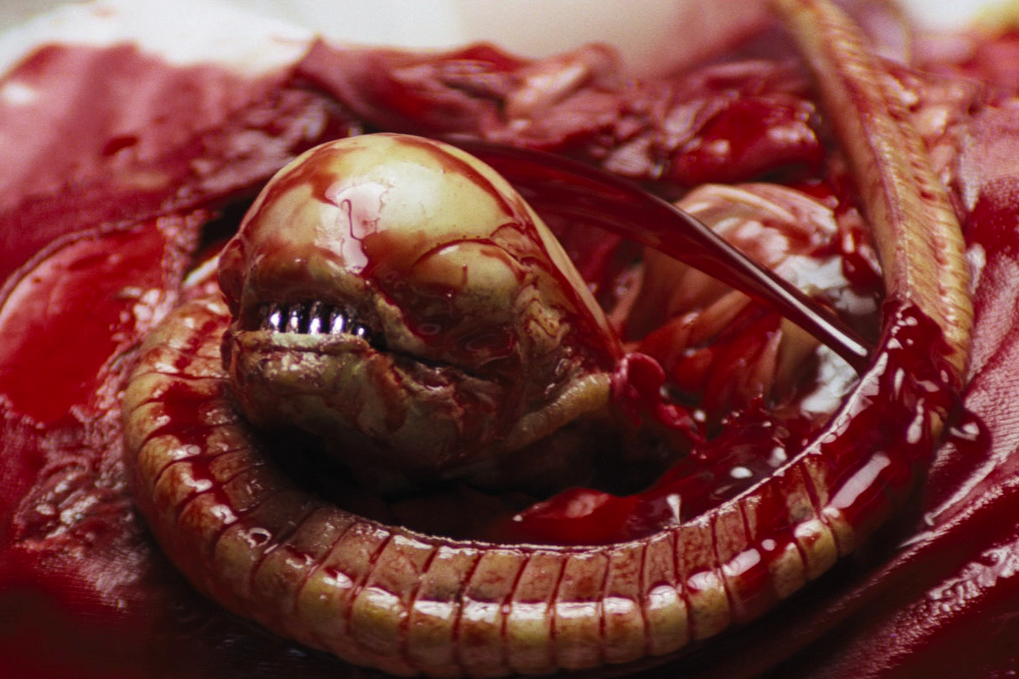

In fact, the low-fi aesthetic is part of the reason it still feels fresh. It was only Scott’s second feature. Coming from advertising, he knew the importance of setting mood and tone in as short a space of time as possible. Although the film is set in futuristic deep space, the Nostromo feels as claustrophobic and real as a basement. In his review at the time, Derek Malcolm wrote that Scott and his special effects team had created “a sweaty little world on its own”. This was very much the plan. John Hurt said that Scott wanted his ship to feel as if it had been drifting around space for “donkey’s years”. The interior of the ship was cobbled together from the skeletons of old planes. For the facehugger dissection, oysters were stuffed into a mould. When the baby alien explodes from John Hurt’s chest, the reaction on Cartwright’s face was real: the actors had not been told what was about to happen. Rather than elaborate CGI, the aliens are rubber suits and puppets. A layer of smoke was blown through the whole set, too thin to be seen but enough to give the film a gritty, murky film. “It’s basically a haunted house film,” the critic David Thomson explained. “The only difference is that the old dark house just happens to be a spaceship.”

Yet it is also true that some of Alien’s themes have grown more pertinent since it appeared. On its original release some critics saw it as a reaction to Vietnam, with the crew of the Nostromo engaged in guerrilla warfare against an unknown and often invisible enemy. Certainly it has some of that intensity, which it shares with other action films of the late Seventies and early Eighties. (It was released in the same year as The Deer Hunter, which confronted the themes head on.) With the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq fading from memory, that kind of fighting feels less relevant to the viewer in 2019.

These days other elements appear in the foreground. Compared to the aristocracy of Star Wars, where the Force is something you are either born with or not, or the techno-meritocracy of Star Trek, where ships are full of insufferable nerds, the world of Alien is refreshingly blue-collar. These things will eat you regardless of your rank. Their design still inspires revulsion. As Thompson has said, Alien is a rape film in which the victims are male. Using a proboscis to force eggs deep in a host’s body, the aliens mirror human sexual reproduction. The adult xenomorph’s mouth, in which sharp teeth part to reveal another sharp-toothed proboscis, a phallus with a kind of vagina dentata at the end, is all horrors to all people.

Rewatching Alien on an unseasonably hot February, I found it hard not to feel the inklings of a climate reading, too, with the Nostromo as Earth itself; a haven hurtling through a hostile universe, into which humans in their recklessness have introduced new existential threats. When the environment is so hostile, even banding together might not save you: nobody can hear you scream.

The gender politics have never felt more acute, and it’s noticeable that few of the contemporary reviews make mention of it. (In general they fail to identify the film as the masterpiece it is now acknowledged to be, preferring to focus on its cheap thrills.) The film was never intended to be a feminist statement. Famously, Ripley was meant to be a male character until late in the day. Sigourney Weaver was cast just weeks before shooting, apparently after a tip-off from Warren Beatty. Scott built an entire set just to audition her.

In an interview looking back at the role, Weaver said: “The writers were especially smart in that they didn’t turn Ripley into a female character. She was just a character, a kind of Everyman, a young person who’s put in this extraordinary situation. Believe me, when we did [the sequels], I saw how hard it was to write a woman in a heroic, straight, unsentimental, authentic way.”

Her intelligence and resolve against the bigger threats, in a world full of aggressive, violent men, remain a benchmark in an era of #MeToo. The consensus is that this feminist message was let down somewhat by the decision to have Ripley strip to her underwear in the final act. But within cinema, Alien’s central lesson that competent women will save the day has echoes in everything from Star Wars to Frozen.

To dip into the Alien forums online is to open the door to a room full of people who really don’t like Ridley Scott. It’s true his most recent contributions, Prometheus and Alien: Covenant, have been underwhelming, overdependent on CGI. Like George Lucas with the Star Wars prequels, Scott appears to have got bogged down in his own mythology, and lost sight of the tautness that made the original so compelling. As with many great films, Alien was the consequence of a unique and perhaps unrepeatable set of circumstances. In the wake of Star Wars, the studio wanted a sci-fi, and Alien was the only script on their desk. Ridley Scott was not the first choice of director, but the right man in the right place. The other elements clicked. In a retrospective interview, the director said he simply “wanted to scare the s*** out of people. That’s the job.” Forty years on it is clear he did precisely that and much more besides.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks